Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2026; 17(3):564-570. doi:10.7150/jca.128357 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Potential influence of omentin-1 genetic variants on the clinicopathological features of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

1. School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

2. Department of Family Medicine, China Medical University Hsinchu Hospital, Hsinchu, Taiwan.

3. School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

4. Department of Surgery, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

5. Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

6. Division of General Surgery, Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan.

7. Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

8. Department of Medical Research, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

9. Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

10. Department of Medical Laboratory Science and Biotechnology, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan.

11. Chinese Medicine Research Center, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

# These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-11-14; Accepted 2026-1-28; Published 2026-2-18

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks as the fifth supreme prevalent cancer within men globally and the ninth among female, serving as a significant contributor to cancer-associated deaths. The adipokine omentin-1 has been demonstrated to have a defensive effect by decreasing the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. The connections among lifestyle factors that promote cancer, OMNT1 polymorphisms, and HCC are still not well understood. Our investigation focused on the influence of clinicopathological characteristics and four variants of the OMNT1 gene (rs2274907, rs35779394, rs4656959, and rs79209815) on healthy controls as well as Taiwanese individuals with HCC. According to our data, individuals with the OMNT1 rs79209815 variant (TC or CC genotypes) are at an elevated risk of progressing to stage III/IV disease and larger tumors than those with the TT genotype. Males exhibited these associations more prominently than females. Moreover, OMNT1 expression levels were markedly reduced in individuals with the wild-type TT homozygous genotype when compared to those with the TC or CC genotypes of rs79209815. The complexity of genetic influences on HCC is highlighted by our study, which suggests that OMNT1 polymorphisms may have an impact on tumor stage and progression.

Keywords: Omentin-1, Hepatocellular carcinoma, genetic polymorphisms, rs79209815

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks as the fifth supreme prevalent cancer within men globally and the ninth among female, serving as a significant contributor to cancer-related deaths [1]. HCC correlates with a low five-year survival rate and rising mortality rates [2, 3]. In Taiwan, the second most common reason of cancer-related fatalities is HCC [4, 5]. Genetic variation is crucial for susceptibility to HCC and its progression. Most individuals who encounter the recognized infectious or environmental risk mediators (such as alcohol misuse, hepatitis virus infection, or non-alcoholic fatty liver disorder linked to insulin resistance, diabetes or obesity) do not go on to progress HCC. This implies that personal susceptibility plays a role in tumorigenesis [6, 7]. Data on the frequency of genotype distribution can help to chart single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) diversity within a population and investigate the risk and progression of certain disorders [8, 9]. Investigations that have recently come to light suggest a link between SNPs in specific genes and the vulnerability to and clinicopathological status of HCC.

Adipokines are bioactive agents secreted by adipose tissue that regulate a range of physiological processes, including inflammation, homeostasis, insulin responsiveness, and immune responses [10, 11]. Metabolic and inflammatory pathways are influenced by key adipokines for instance omentin-1, adiponectin, resistin and leptin, which act locally or systemically through endocrine, autocrine, or paracrine processes [12]. Adipokines have multifaceted effects in cancer, impacting the tumor microenvironment, cellular proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metastasis [13]. Omentin-1 have identified adipokine consisting of 313 amino acids, is primarily generated in the small intestine as well as in adipose tissue and omental [14, 15]. Omentin-1 exhibits anti-hyperinsulinemic and anti-inflammatory functions [16]. It has been documented to play a protective effect in decreasing proinflammatory cytokine generation [17]. Previous experimental studies have shown that omentin-1 is positively linked with increased levels of anti-inflammatory mediators [18, 19]. In the context of cancer, there is an inverse relationship between serum omentin-1 levels and obesity, indicating that omentin-1 could be a marker for cancer development [20]. Moreover, omentin-1 might act as a tumor-suppressor mediator, given that patients with renal cell carcinoma have been observed to have lower serum levels of omentin-1 [21]. No data are available on the links between carcinogenic lifestyle factors, OMNT1 gene polymorphisms, and HCC. Consequently, this research investigated the impact of carcinogenic lifestyle factors and OMNT1 gene polymorphisms on the likelihood of HCC development in a cohort of Taiwanese. We also investigated the relationships between OMNT1 genotypes and the histopathological prognostic variables of HCC.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

We registered 413 patients with HCC at Chung Shan Medical University Hospital in Taiwan. From the Taiwan Biobank Project, 826 healthy controls (HCs) with no cancer history were randomly chosen and anonymized. Every participant in the study belonged to the Han Chinese ethnicity. Patients with HCC were staged using the 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system, which takes into account tumor morphology, the number of affected lymph nodes, and metastases [22]. Prior to entering the study, each participant gave informed written consent and filled out a structured questionnaire regarding their sociodemographic status, as well as their use of alcohol and cigarettes. A diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was made based on biopsy results, suitable sagittal CT or MRI scans, or biochemical indicators of liver parenchymal damage accompanied by endoscopic esophageal or gastric varices. Before the study began, it received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital.

Selection and genotyping of SNPs

The OMNT1 SNPs rs2274907, rs35779394, rs4656959, and rs79209815 were selected based on previous reports [23, 24]. Every SNP had a minor allele frequency greater than 5%. Genomic DNA was extracted from 3 mL peripheral blood samples using QIAamp DNA Blood Kits (Qiagen, CA, USA). Using previously described assessment techniques [8, 20, 21], allelic discrimination was performed on the SNPs. RT-qPCR experiments and the isolation of RNA were performed following the protocols we published earlier [25, 26].

Analysis of clinical dataset

The GTEx portal (gtexportal.org/home/) serves as a comprehensive public resource for the analysis of gene levels and modulation specific to various tissues. It provides quantitative trait loci (QTLs), histological images, and gene expression data that is open-access [27].

Statistical analysis

To assess the differences between the HCC and control groups, the Fisher's exact test and Mann-Whitney U test were employed, with p-values below 0.05 considered statistically significant. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between genotype frequencies and HCC risk. The collected data were analyzed using version 9.1 of the Statistical Analytic System (SAS) software.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the 413 patients with HCC and the 826 cancer-free HCs) did not show significant differences (Table 1). Controls reported alcohol consumption significantly less often than patients (p < 0.001), but there was no difference in cigarette smoking status between the two groups (p = 0.409) (Table 1). The proportions of HCC patients who tested positive for HBsAg (44.8%) and anti- HCV antibodies (36.6%) (Table 1). At the time of enrollment in the study, 310 patients (75.1%) presented with stage I/II HCC, while 103 (24.9%) had stage III/IV disease. Patients with HCC also presented with N1+N2+N3 lymph node status (2.2%), metastasis (5.8%) and vascular invasion (12.3%). Liver cirrhosis was present in most patients (86.2%) (Table 1).

Genotyping results for the OMNT1 SNPs in HCs and HCC patients are shown in Table 2. The homozygous T/T alleles for rs2274907, rs35779394, and rs79209815, as well as the homozygous A/A allele for rs4656959, were the most common (Table 2). After adjusting for age, gender, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption (Table 2), none of the genotypes for the four OMNT1 SNPs across different groups exhibited notable associations.

The distributions of demographical characteristics in 826 controls and 413 patients with HCC.

| Variable | Controls (N=826) | Patients (N=413) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | |||

| <60 | 322 (39.0%) | 140 (33.9%) | p = 0.081 |

| ≥ 60 | 504 (61.0%) | 273 (66.1%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 612 (74.1%) | 289 (70.0%) | p = 0.125 |

| Female | 214 (25.9%) | 124 (30.0%) | |

| Cigarette smoking | |||

| No | 502 (60.8%) | 261 (63.2%) | p = 0.409 |

| Yes | 324 (39.2%) | 152 (36.8%) | |

| Alcohol drinking | |||

| No | 701 (84.9%) | 284 (68.8%) | p < 0.001* |

| Yes | 125 (15.1%) | 129 (31.2%) | |

| HBsAg | |||

| Negative | 228 (55.2%) | ||

| Positive | 185 (44.8%) | ||

| Anti-HCV | |||

| Negative | 262 (63.4%) | ||

| Positive | 151 (36.6%) | ||

| Stage | |||

| I+II | 310 (75.1%) | ||

| III+IV | 103 (24.9%) | ||

| Tumor T status | |||

| T1+T2 | 315 (76.3%) | ||

| T3+T4 | 98 (23.7%) | ||

| Lymph node status | |||

| N0 | 404 (97.8%) | ||

| N1+N2+N3 | 9 (2.2%) | ||

| Metastasis | |||

| M0 | 389 (94.2%) | ||

| M1 | 24 (5.8%) | ||

| Vascular invasion | |||

| No | 362 (87.7%) | ||

| Yes | 51 (12.3%) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | |||

| Negative | 57 (13.8%) | ||

| Positive | 356 (86.2%) |

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Genotyping and allele frequency of OMNT1 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in HCC and normal controls.

| Variable | Controls (N=826) (%) | Patients (N=413) (%) | AOR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2274907 | ||||

| TT | 367 (44.4%) | 181 (43.8%) | 1.000 (reference) | |

| TA | 377 (45.6%) | 189 (45.8%) | 0.998 (0.772~1.291) | p=0.989 |

| AA | 82 (10.0%) | 43 (10.4%) | 1.091 (0.715~1.664) | p=0.687 |

| TA+AA | 459 (55.6%) | 232 (56.2%) | 1.014 (0.794~1.296) | p=0.909 |

| rs35779394 | ||||

| TT | 645 (78.1%) | 310 (75.1%) | 1.000 (reference) | |

| TC | 166 (20.1%) | 92 (22.3%) | 1.186 (0.879~1.599) | p=0.265 |

| CC | 15 (1.8%) | 11 (2.7%) | 1.547 (0.689~3.473) | p=0.291 |

| TC+CC | 181 (21.9%) | 103 (24.9%) | 1.216 (0.913~1.622) | p=0.182 |

| rs4656959 | ||||

| AA | 379 (45.9%) | 186 (45.0%) | 1.000 (reference) | |

| AG | 367 (44.4%) | 185 (44.8%) | 1.010 (0.781~1.305) | p=0.939 |

| GG | 80 (9.7%) | 42 (10.2%) | 1.083 (0.708~1.658) | p=0.713 |

| AG+GG | 447 (54.1%) | 227 (55.0%) | 1.023 (0.801~1.306) | p=0.856 |

| rs79209815 | ||||

| TT | 708 (85.7%) | 361 (87.4%) | 1.000 (reference) | |

| TC | 112 (13.6%) | 45 (10.9%) | 0.783 (0.535~1.145) | p=0.207 |

| CC | 6 (0.7%) | 7 (1.7%) | 2.327 (0.756~7.157) | p=0.141 |

| TC+CC | 118 (14.3%) | 52 (12.6%) | 0.861 (0.600~1.236) | p=0.419 |

Adjusted for the effects of age, gender, cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking.

Next, we conducted a comparison of the distributions of clinical aspects and OMNT1 genotypes among HCC patients. No significant influence of SNPs rs2274907, rs35779394 and rs4656959 on clinicopathologic traits in HCC patients (Table 3). However, compared with patients with the T/T genotype, those with at least one polymorphic C allele at the rs79209815 SNP (T/C+C/C genotype) were susceptible to progressing to stage III/IV disease (OR, 1.899; 95% CI, 1.027~3.512; p<0.05) and large tumors (OR, 2.055; 95% CI, 1.109~3.810; p<0.05) (Table 4). The TC or CC genotypes at rs79209815 were related with an increased risk of stage III/IV disease (OR, 2.298; 95% CI, 1.142-4.622; p < 0.05) and larger tumors (OR, 2.298; 95% CI, 1.142-4.622; p < 0.05) in male, but not female, patients compared with the TT genotype (Table 5).

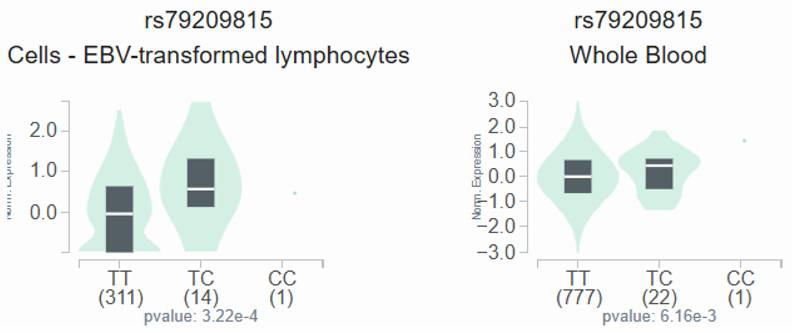

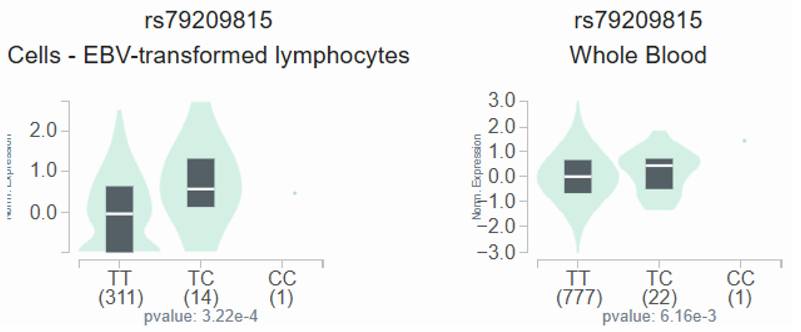

GTEx data indicate that, in lymphocytes and whole blood, individuals carrying the C variant at rs79209815 showed a trend toward augmented omentin-1 expression compared with those with the wild-type TT homozygous genotype (Figure 1).

Discussion

Many cancer reports have confirmed the effectiveness of biomarkers based on genetic aberrations related to tumors in assessing risk, aiding in early diagnosis, and predicting treatment results [28, 29]. Approximately 1% of the overall population carries genetic polymorphisms, which are variations in genomic sequences among individuals. Repetitive sequences most frequently exhibit alterations in the form of SNPs [30]. An expanding body of investigation has recently underscored the significance of SNPs and other genetic changes in predicting and defining pharmacotherapeutic functions in HCC [31, 32]. Moreover, the methodical identification of functional variants linked to cancer risk has demonstrated how SNPs in functional domains affect gene level and tumor susceptibility, highlighting the importance of SNPs in tumor biology [33]. These findings are supplemented by thorough reviews that detail the biological and molecular processes through which SNPs affect gene expression, thereby affecting the progression and development of tumor [34]. Hypothesis-driven genetic research has informed both case-control and prospective cohort reports that investigated the connection between SNPs and HCC. The studies have underscored the connection between changes impacting multiple biological mechanisms—for instance oxidative stress, DNA repair, and inflammation processes—and the evolution of liver cancer in patients with hepatitis [35]. We investigated polymorphisms in the OMNT1 gene and noted their different distributions among HCC patients. Our investigation showed that patients with the T/C+C/C genotypes of rs79209815 exhibited a significantly elevated risk of progressing stage III/IV disease and large tumors.

The OMNT1 shows a substantial eQTL association with rs79209815 genotypes in lymphocytes and whole blood samples from the GTEx database.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the clinical status and OMNT1 rs2274907 and rs35779394 genotypic frequencies in 413 patients with HCC.

| Variable | rs2274907 | rs35779394 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT (N=181) | TA+AA (N=232) | OR (95% CI) | p value | TT (N=310) | TC+CC (N=103) | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Clinical Stage | ||||||||

| Stage I/II | 139 (76.8%) | 171 (73.7%) | 1.000 | 0.472 | 233 (75.2%) | 77 (74.8%) | 1.000 | 0.935 |

| Stage III/IV | 42 (23.2%) | 61 (26.3%) | 1.181 (0.751~1.856) | 77 (24.8%) | 26 (25.2%) | 1.022 (0.611~1.708) | ||

| Tumor size | ||||||||

| T1+T2 | 141 (77.9%) | 174 (75.0%) | 1.000 | 0.492 | 238 (76.8%) | 77 (74.8%) | 1.000 | 0.677 |

| T3+T4 | 40 (22.1%) | 58 (25.0%) | 1.175 (0.742~1.861) | 72 (23.2%) | 26 (25.2%) | 1.116 (0.666~1.872) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||||

| No | 179 (98.9%) | 225 (97.0%) | 1.000 | 0.187 | 303 (97.7%) | 101 (98.1%) | 1.000 | 0.849 |

| Yes | 2 (1.1%) | 7 (3.0%) | 2.784 (0.571~13.568) | 7 (2.3%) | 2 (1.9%) | 0.857 (0.175~4.193) | ||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||

| No | 173 (95.6%) | 216 (93.1%) | 1.000 | 0.286 | 289 (93.2%) | 100 (97.1%) | 1.000 | 0.147 |

| Yes | 8 (4.4%) | 16 (6.9%) | 1.602 (0.670~3.831) | 21 (6.8%) | 3 (2.9%) | 0.413 (0.121~1.414) | ||

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||

| No | 157 (86.7%) | 205 (88.4%) | 1.000 | 0.619 | 269 (86.8%) | 93 (90.3%) | 1.000 | 0.347 |

| Yes | 24 (13.3%) | 27 (11.6%) | 0.862 (0.479~1.551) | 41 (13.2%) | 10 (9.7%) | 0.705 (0.340~1.464) | ||

| HBsAg | ||||||||

| Negative | 94 (51.9%) | 134 (57.8%) | 1.000 | 0.238 | 171 (55.2%) | 57 (55.3%) | 1.000 | 0.975 |

| Positive | 87 (48.1%) | 98 (42.2%) | 0.790 (0.534~1.168) | 139 (44.8%) | 46 (44.7%) | 0.993 (0.634~1.554) | ||

| Anti-HCV | ||||||||

| Negative | 116 (64.1%) | 146 (62.9%) | 1.000 | 0.809 | 198 (63.9%) | 64 (62.1%) | 1.000 | 0.751 |

| Positive | 65 (35.9%) | 86 (37.1%) | 1.051 (0.702~1.574) | 112 (36.1%) | 39 (37.9%) | 1.077 (0.680~1.708) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||||||

| Negative | 25 (13.8%) | 32 (13.8%) | 1.000 | 0.996 | 45 (14.5%) | 12 (11.7%) | 1.000 | 0.465 |

| Positive | 156 (86.2%) | 200 (86.2%) | 1.002 (0.570~1.760) | 265 (85.5%) | 91 (88.3%) | 1.288 (0.652~2.541) | ||

ORs with their 95% CIs were estimated by logistic regression models.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the clinical status and OMNT1 rs4656959 and rs79209815 genotypic frequencies in 413 patients with HCC.

| Variable | rs4656959 | rs79209815 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA (N=186) | AG+GG (N=227) | OR (95% CI) | p value | TT (N=361) | TC+CC (N=52) | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Clinical Stage | ||||||||

| Stage I/II | 141 (75.8%) | 169 (74.4%) | 1.000 | 0.751 | 277 (76.7%) | 33 (74.4%) | 1.000 | 0.039* |

| Stage III/IV | 45 (24.2%) | 58 (25.6%) | 1.075 (0.686~1.685) | 84 (23.3%) | 19 (25.6%) | 1.899 (1.027~3.512) | ||

| Tumor size | ||||||||

| T1+T2 | 143 (76.9%) | 172 (75.8%) | 1.000 | 0.792 | 282 (78.1%) | 33 (63.5%) | 1.000 | 0.020* |

| T3+T4 | 43 (23.1%) | 55 (24.2%) | 1.063 (0.674~1.679) | 79 (21.9%) | 19 (36.5%) | 2.055 (1.109~3.810) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||||

| No | 183 (98.4%) | 221 (97.7%) | 1.000 | 0.476 | 354 (98.1%) | 50 (96.2%) | 1.000 | 0.379 |

| Yes | 3 (1.6%) | 6 (2.6%) | 1.656 (0.409~6.714) | 7 (1.9%) | 2 (3.8%) | 2.023 (0.409~10.010) | ||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||

| No | 177 (95.2%) | 212 (93.4%) | 1.000 | 0.444 | 338 (93.6%) | 51 (98.1%) | 1.000 | 0.200 |

| Yes | 9 (4.8%) | 15 (6.6%) | 1.392 (0.595~3.256) | 23 (6.4%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0.288 (0.038~2.180) | ||

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||

| No | 161 (86.6%) | 201 (88.5%) | 1.000 | 0.541 | 318 (88.1%) | 44 (84.6%) | 1.000 | 0.477 |

| Yes | 25 (13.4%) | 26 (11.5%) | 0.833 (0.463~1.498) | 43 (11.9%) | 8 (15.4%) | 1.345 (0.593~3.046) | ||

| HBsAg | ||||||||

| Negative | 98 (52.7%) | 130 (57.3%) | 1.000 | 0.352 | 201 (55.7%) | 27 (51.9%) | 1.000 | 0.611 |

| Positive | 88 (47.3%) | 97 (42.7%) | 0.831 (0.563~1.227) | 160 (44.3%) | 25 (48.1%) | 1.163 (0.650~2.082) | ||

| Anti-HCV | ||||||||

| Negative | 118 (63.4%) | 144 (63.4%) | 1.000 | 0.999 | 224 (62.0%) | 38 (73.1%) | 1.000 | 0.123 |

| Positive | 68 (36.6%) | 83 (36.6%) | 1.000 (0.669~1.496) | 137 (38.0%) | 14 (26.9%) | 0.602 (0.315~1.152) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||||||

| Negative | 26 (14.0%) | 31 (13.7%) | 1.000 | 0.925 | 48 (13.3%) | 9 (17.3%) | 1.000 | 0.433 |

| Positive | 160 (86.0%) | 196 (86.3%) | 1.027 (0.586~1.801) | 313 (86.7%) | 43 (82.7%) | 0.733 (0.336~1.598) | ||

ORs with their 95% CIs were estimated by logistic regression models. * p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for clinical status and the genotypic frequencies of OMNT1 rs79209815 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients stratified by gender.

| Variable | Male (N=289) | Female (N=124) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT (N=249) | TC+CC (N=40) | OR (95% CI) | p value | TT (N=112) | TC+CC (N=12) | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Clinical Stage | ||||||||

| Stage I/II | 193 (77.5%) | 24 (60.0%) | 1.000 | 0.017* | 84 (75.0%) | 9 (75.0%) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Stage III/IV | 56 (22.5%) | 16 (40.0%) | 2.298 (1.142~4.622) | 28 (25.0%) | 3 (25.0%) | 1.000 (0.253~3.955) | ||

| Tumor size | ||||||||

| T1+T2 | 193 (77.5%) | 24 (60.0%) | 1.000 | 0.017* | 89 (79.5%) | 9 (75.0%) | 1.000 | 0.718 |

| T3+T4 | 56 (22.5%) | 16 (40.0%) | 2.298 (1.142~4.622) | 23 (20.5%) | 3 (25.0%) | 1.290 (0.323~5.151) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||||

| No | 244 (98.0%) | 38 (95.0%) | 1.000 | 0.253 | 110 (98.2%) | 12 (100.0%) | 1.000 | 0.641 |

| Yes | 5 (2.0%) | 2 (5.0%) | 2.568 (0.481~13.713) | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | ---- | ||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||||

| No | 232 (93.2%) | 39 (97.5%) | 1.000 | 0.293 | 106 (94.6%) | 12 (100.0%) | 1.000 | 0.411 |

| Yes | 17 (6.8%) | 1 (2.5%) | 0.350 (0.045~2.705) | 6 (5.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | ---- | ||

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||

| No | 217 (87.1%) | 33 (82.5%) | 1.000 | 0.424 | 101 (90.2%) | 11 (91.7%) | 1.000 | 0.868 |

| Yes | 32 (12.9%) | 7 (17.5%) | 1.438 (0.587~3.524) | 11 (9.8%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0.835 (0.098~7.092) | ||

| HBsAg | ||||||||

| Negative | 131 (52.6%) | 20 (50.0%) | 1.000 | 0.759 | 70 (62.5%) | 7 (58.3%) | 1.000 | 0.777 |

| Positive | 118 (47.4%) | 20 (50.0%) | 1.110 (0.569~2.165) | 42 (37.5%) | 5 (41.7%) | 1.190 (0.355~3.991) | ||

| Anti-HCV | ||||||||

| Negative | 167 (67.1%) | 28 (70.0%) | 1.000 | 0.713 | 57 (50.9%) | 10 (83.3%) | 1.000 | 0.032 |

| Positive | 82 (32.9%) | 12 (30.0%) | 0.873 (0.422~1.804) | 55 (49.1%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0.207 (0.043~0.989) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||||||

| Negative | 35 (14.1%) | 8 (20.0%) | 1.000 | 0.327 | 13 (11.6%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1.000 | 0.733 |

| Positive | 214 (85.9%) | 32 (80.0%) | 0.654 (0.279~1.536) | 99 (88.4%) | 11 (91.7%) | 1.444 (0.172~12.121) | ||

ORs with their 95% CIs were estimated by logistic regression models. * p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Adipokines are unique bioactive peptides released by adipose tissues and play a role in various bodily functions [36, 37]. To examine the function of adipose tissue in the progression of inflammation and carcinogenesis, many investigators have been investigating this issue for the last two decades [38, 39]. Recent studies have documented that omentin-1 plays a vital effect in cell differentiation and the promotion of cancer cell death [40]. Many associated studies found that the levels of omentin-1 in circulation among patients with colorectal and renal cell carcinoma differed, suggesting that omentin-1 might play a part in cancer development [41]. Recently, omentin-1 SNPs have been investigated in several cancers. For example, in OSCC, the TA and AA genotypes of SNP rs2274907 were related with an augmented risk of progressing to an advanced clinical stage compared with the TT genotype [23]. The OMNT1 rs2274907 and rs4656959 variants are protective against perineural invasion, particularly in prostate cancer patients without biochemical recurrence [24]. Conversely, research on omentin-1 and HCC is limited. We conducted this study to compare the allelic distributions of OMNT1 gene polymorphisms between HCs and HCC patients. Carriers of at least one C allele (genotypes TC or CC) at the OMNT1 SNP rs79209815 exhibited a heightened risk for developing stage III/IV disease and larger tumors, according to our findings. It is worth mentioning that these correlations were more marked in male patients than in female ones. Furthermore, there was a tendency for the omentin-1 expression to be higher in individuals with the C variant at rs79209815 than in those with the wild-type TT homozygous genotype. Omentin-1 levels are thus crucially linked to the advancement of HCC in patients. It is important to note the limitations of the current study. More research is required, which calls for a larger sample size and a longer follow-up time. Furthermore, an independent cohort of HCC cases from Taiwanese communities and other cohorts found in open-access databases must be used to confirm the current findings.

To sum up, our study is the first to uncover links between OMNT1 gene variants and HCC. The OMNT1 rs79209815 variant (genotypes TC or CC) is linked to a heightened risk of developing stage III/IV disease and larger tumors, especially among male HCC patients, as our findings suggest. Moreover, the wild-type TT homozygous genotype was linked to considerably reduced OMNT1 expression levels in comparison to the TC or CC genotypes of rs79209815, suggesting that this OMNT1 SNP plays a crucial role in HCC development.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (NSTC 113-2320-B-039-049-MY3; NSTC112-2314-B-039-018-MY3); China Medical University Hsinchu Hospital (CMUHCH-DMR-113-021; CMUHCH-DMR-114-025); Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (CSH-2023-C-010).

Competing Interests

The authors have no financial or personal relationships that could inappropriately influence this research.

References

1. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63:11-30

2. Blechacz B, Mishra L. Hepatocellular carcinoma biology. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2013;190:1-20

3. Ezzikouri S, Benjelloun S, Pineau P. Human genetic variation and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma development. Hepatology international. 2013;7:820-31

4. Bosch FX, Ribes J, Cleries R, Diaz M. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2005;9:191-211 v

5. Wu CY, Huang HM, Cho DY. An acute bleeding metastatic spinal tumor from HCC causes an acute onset of cauda equina syndrome. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2015;5:18

6. Wang B, Hsu CJ, Lee HL, Chou CH, Su CM, Yang SF. et al. Impact of matrix metalloproteinase-11 gene polymorphisms upon the development and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. International journal of medical sciences. 2018;15:653-8

7. Mohamed Y, Basyony MA, El-Desouki NI, Abdo WS, El-Magd MA. The potential therapeutic effect for melatonin and mesenchymal stem cells on hepatocellular carcinoma. BioMedicine. 2019;9:24

8. Shastry BS. SNP alleles in human disease and evolution. Journal of human genetics. 2002;47:561-6

9. Wang B, Hsu CJ, Chou CH, Lee HL, Chiang WL, Su CM. et al. Variations in the AURKA Gene: Biomarkers for the Development and Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. International journal of medical sciences. 2018;15:170-5

10. MᵃᶜDonald IJ, Liu SC, Huang CC, Kuo SJ, Tsai CH, Tang CH. Associations between Adipokines in Arthritic Disease and Implications for Obesity. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 20

11. Lin TH, Liu SC, Huang YL, Lai CY, He XY, Tsai CH. et al. Apelin facilitates integrin αvβ3 production and enhances metastasis in prostate cancer by activating STAT3 and inhibiting miR-8070. International journal of biological sciences. 2025;21:4117-28

12. Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11:85-97

13. Grigoraș A, Amalinei C. The Role of Perirenal Adipose Tissue in Carcinogenesis-From Molecular Mechanism to Therapeutic Perspectives. Cancers. 2025 17

14. Schäffler A, Neumeier M, Herfarth H, Fürst A, Schölmerich J, Büchler C. Genomic structure of human omentin, a new adipocytokine expressed in omental adipose tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1732:96-102

15. Chang JW, Tang CH. The role of macrophage polarization in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;142:113056

16. Li Z, Liu B, Zhao D, Wang B, Liu Y, Zhang Y. et al. Omentin-1 prevents cartilage matrix destruction by regulating matrix metalloproteinases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;92:265-9

17. Rao SS, Hu Y, Xie PL, Cao J, Wang ZX, Liu JH. et al. Omentin-1 prevents inflammation-induced osteoporosis by downregulating the pro-inflammatory cytokines. Bone Res. 2018;6:9

18. Lin YY, Huang CC, Ko CY, Tsai CH, Chang JW, Achudhan D. et al. Omentin-1 modulates interleukin expression and macrophage polarization: Implications for rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;149:114205

19. Ko CY, Lin YY, Achudhan D, Chang JW, Liu SC, Lai CY. et al. Omentin-1 ameliorates the progress of osteoarthritis by promoting IL-4-dependent anti-inflammatory responses and M2 macrophage polarization. International journal of biological sciences. 2023;19:5275-89

20. Kim JW, Kim JH, Lee YJ. The Role of Adipokines in Tumor Progression and Its Association with Obesity. Biomedicines. 2024 12

21. Chinapayan SM, Kuppusamy S, Yap NY, Perumal K, Gobe G, Rajandram R. Potential Value of Visfatin, Omentin-1, Nesfatin-1 and Apelin in Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 12

22. Vauthey JN, Lauwers GY, Esnaola NF, Do KA, Belghiti J, Mirza N. et al. Simplified staging for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1527-36

23. Wu Y-H, Lin C-W, Tsai H-C, Su C-W, Lien M-Y, Yang S-F. et al. Potential impact of omentin-1 genetic variants with the clinical features and progression of buccal mucosa cancer. International journal of medical sciences. 2025;22:3958-64

24. Weng W-C, Lin T-H, He X-Y, Lin C-Y, Wu H-C, Huang Y-L. et al. Potential impact of omentin-1 genetic variants on perineural invasion in prostate cancer. Journal of Cancer. 2025;16:3767-74

25. Lee HP, Chen PC, Wang SW, Fong YC, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ. et al. Plumbagin suppresses endothelial progenitor cell-related angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Functional Foods. 2019;52:537-44

26. Lee HP, Wang SW, Wu YC, Lin LW, Tsai FJ, Yang JS. et al. Soya-cerebroside inhibits VEGF-facilitated angiogenesis in endothelial progenitor cells. Food Agr Immunol. 2020;31:193-204

27. Carithers LJ, Moore HM. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project. Biopreserv Biobank. 2015;13:307-8

28. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546-58

29. MacDonald IJ, Lin CY, Kuo SJ, Su CM, Tang CH. An update on current and future treatment options for chondrosarcoma. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2019;19:773-86

30. Allemailem KS, Almatroudi A, Alrumaihi F, Makki Almansour N, Aldakheel FM, Rather RA. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in prostate cancer: its implications in diagnostics and therapeutics. American journal of translational research. 2021;13:3868-89

31. Hsueh KC, Lee HL, Ho KH, Chang LC, Yang SF, Chien MH. Disease-Associated Risk Variants and Expression Levels of the lncRNA, CDKN2B-AS1, Are Associated With the Progression of HCC. J Cell Mol Med. 2025;29:e70496

32. Chien Y-C, Lee H-L, Chiang W-L, Bai L-Y, Hung Y-J, Chen S-C. et al. Analysis of <i>ZNF208</i> Polymorphisms on the Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Asian Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Journal of Cancer. 2024;15:5183-90

33. Lu H, Wei Y, Jiang Z, Zhang J, Wang T, Huang S. et al. Integrative eQTL-weighted hierarchical Cox models for SNP-set based time-to-event association studies. Journal of translational medicine. 2021;19:418

34. Liu S, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Wu J, Liang J, Yu S. et al. Systematic identification of regulatory variants associated with cancer risk. Genome biology. 2017;18:194

35. Nahon P, Zucman-Rossi J. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 2012;57:663-74

36. Taylor EB. The complex role of adipokines in obesity, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Clinical science (London, England: 1979). 2021;135:731-52

37. Wang YH, Wu YY, Tsai CH, Fong YC, Ko CY, Chen HT. et al. Apelin promotes RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis by activating MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Mol Med Rep. 2026 33

38. Song YC, Lee SE, Jin Y, Park HW, Chun KH, Lee HW. Classifying the Linkage between Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Tumor Growth through Cancer-Associated Adipocytes. Molecules and cells. 2020;43:763-73

39. Huang CL, Ghule SS, Chang YH, Tsai HC, Lien MY, Guo JH. et al. Visfatin facilitates esophageal cancer migration by suppressing miR-3613-5p expression and promoting VEZF1/VCAN production. Oncol Rep. 2025 54

40. Zhang YY, Zhou LM. Omentin-1, a new adipokine, promotes apoptosis through regulating Sirt1-dependent p53 deacetylation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. European journal of pharmacology. 2013;698:137-44

41. Shen XD, Zhang L, Che H, Zhang YY, Yang C, Zhou J. et al. Circulating levels of adipocytokine omentin-1 in patients with renal cell cancer. Cytokine. 2016;77:50-5

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Chih-Hsin Tang, PhD; E-mail: chtangcmu.edu.tw; Shun-Fa Yang, PhD; ysfedu.tw.

Corresponding authors: Chih-Hsin Tang, PhD; E-mail: chtangcmu.edu.tw; Shun-Fa Yang, PhD; ysfedu.tw.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact