Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2026; 17(2):419-426. doi:10.7150/jca.125694 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Association Between Long-term Use of H2 Receptor Antagonists and Prostate Cancer Risk: A Case-Control Study in Taiwan

1. School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

2. Graduate Institute of Biomedical Informatics, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

3. School of Nursing, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

4. Clinical Big Data Research Center, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

5. Graduate Institute of Data Science, College of Management, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

6. Clinical Data Center, Office of Data Science, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

7. Research Center of Health Care Industry Data Science, College of Management, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

8. Department of Health Policy and Management, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

9. Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Middlesex University, London, UK.

10. International Center for Health Information Technology (ICHIT), Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

11. Research Center of Big Data and Meta-analysis, Wanfang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received 2025-9-23; Accepted 2025-12-17; Published 2026-1-14

Abstract

Objective: The association between long-term use of histamine-2 receptor antagonists and prostate cancer remains unclear. This study aimed to examine the age-specific risk of prostate cancer associated with long-term use of these medications.

Methods: We conducted a nationwide case-control study using Taiwan's Health and Welfare Data Science Center database from 2003 to 2016. Men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer were matched to controls, and long-term use was defined as cumulative exposure of sixty days or more. Adjusted odds ratios were estimated using conditional logistic regression, controlling for comorbidities and medications.

Results: Among 43,578 prostate cancer cases and 174,312 controls, long-term use of histamine-2 receptor antagonists was associated with a modest increase in prostate cancer risk, significant in men aged sixty-five and older (adjusted odds ratio = 1.087, 95% CI: 1.044-1.131) but not in younger groups. Cimetidine and ranitidine were each associated with increased risk in older men, while famotidine showed no significant association across age groups. Notably, cimetidine uses in men aged forty to sixty-four was associated with reduced prostate cancer risk (adjusted odds ratio = 0.865, 95% CI: 0.755-0.990), suggesting possible age-dependent effects.

Conclusions: These findings suggest that long-term use of cimetidine and ranitidine may increase prostate cancer risk in older men, while famotidine was not associated with prostate cancer risk. Risk varies by age and drug type, highlighting the need for drug-specific evaluation in cancer pharmacoepidemiology.

Keywords: histamine-2 receptor antagonists, prostate cancer, cancer risk, cimetidine, ranitidine

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer ranks fourth in incidence and eighth in mortality worldwide according to global cancer statistics in 2022 [1], being the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men across 118 countries, with 1.47 million new cases and 396,792 deaths annually [2, 3]. Androgen signaling plays a central role in prostate cancer development and progression, and age-related hormonal changes may influence individual susceptibility [4-6]. While age, genetic predisposition, dietary habits, and environmental exposures are well-established risk factors [7-9], the possible role of long-term medication use in prostate cancer development has received relatively limited attention in epidemiological research.

Histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H₂RAs), including ranitidine, cimetidine, and famotidine, have been widely used to treat acid-related gastrointestinal disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease and peptic ulcers. Among them, cimetidine has been associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer in individuals who used it daily for 10 years when compared to non-users, while short-term use has shown no such association, possibly due to its inhibition of dihydrotestosterone binding to androgen receptors, increased plasma estradiol concentrations, and elevated prolactin levels, a potential growth factor for prostate cancer [10]. Supporting this hypothesis, a 9-week high-dose cimetidine study in animals further suggested a potential link between cimetidine exposure and prostate carcinogenesis [11].

Notably, ranitidine has been the primary focus of cancer risk studies due to concerns regarding its contamination with N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a probable human carcinogen classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [12-14]. However, epidemiological studies on ranitidine use and cancer risk have reported inconsistent findings across different cancer types. A multinational cohort study using 12 international healthcare databases found no association between ranitidine use (≥30 cumulative days) and overall cancer incidence compared to other H₂RA users [15]. Similarly, an analysis of medical data found no increased risk of overall or prostate cancer in ranitidine or nizatidine users compared to other H₂RA users, nor a significant dose-response relationship [16]. In contrast, research indicated that individuals with at least 90 defined daily doses of ranitidine had a higher risk of liver, gastric, pancreatic, and lung cancers compared to non-users and famotidine users [17]. Additionally, an analysis of bladder cancer risk found an increased incidence among individuals with at least three years of continuous ranitidine use compared to non-users [18].

Despite growing interest in cancer risk, studies focusing specifically on prostate cancer concerning H₂RA use remain scarce. Although ranitidine has been withdrawn from the market, other H₂RAs remain in use. Understanding the overall impact of H₂RA use, including historical exposure, is important for evaluating potential long-term risks or preventive effects. Moreover, a key limitation in existing research is the lack of age-stratified analyses. Since prostate cancer risk increases with age, and older adults tend to use H₂RAs more frequently and for longer durations, their cumulative exposure may differ significantly from younger individuals. Thus, this study aimed to explore the association between the long-term use of H₂RAs and prostate cancer risk across different age groups.

2. Methods

2.1 Data Resources

This population-based case-control study utilized data from the Taiwan Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC) databases managed by Taiwan's Ministry of Health and Welfare [19]. The HWDC databases have been in operation since Taiwan's National Health Insurance program was implemented in 1995. Covering 99.9% of Taiwan's population, approximately 23 million individuals, these databases provide comprehensive healthcare information, including outpatient and inpatient records, cancer registry data, and other healthcare-related datasets. [20]. This integrated database contains detailed information on demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender) and medical history (e.g., comorbidities, medication use, and healthcare utilization). The cancer registry database includes data on cancer diagnoses, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification, diagnosis dates, histopathological confirmation, and primary treatment modalities such as surgery, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy [19]. This study was approved by the Taipei Medical University - Joint Institutional Review Board (TMU-JIRB), under approval number N202003069.

2.2 Study Population

The study population consisted of individuals diagnosed with prostate cancer and a matched control group. Prostate cancer cases were defined as those who received their first prostate cancer diagnosis, as recorded in the cancer registry database, between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2016. Individuals were excluded from the study if they had a previous cancer diagnosis between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2002, were younger than 20 years of age, had unknown sex, or had a diagnosis date that was inconsistent or could not be identified. To ensure that only newly diagnosed prostate cancer cases were included and to minimize the risk of misclassification due to pre-existing diagnoses, a two-year washout period (2001-2002) was implemented.

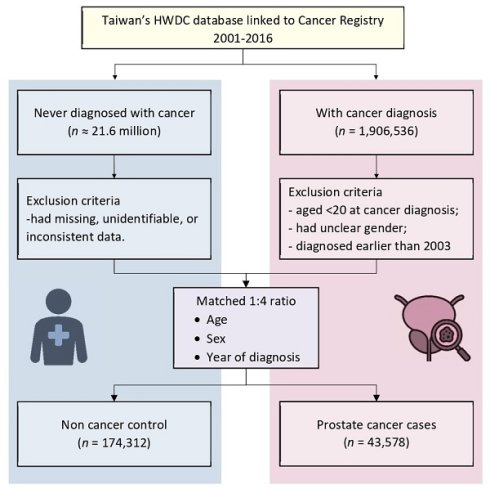

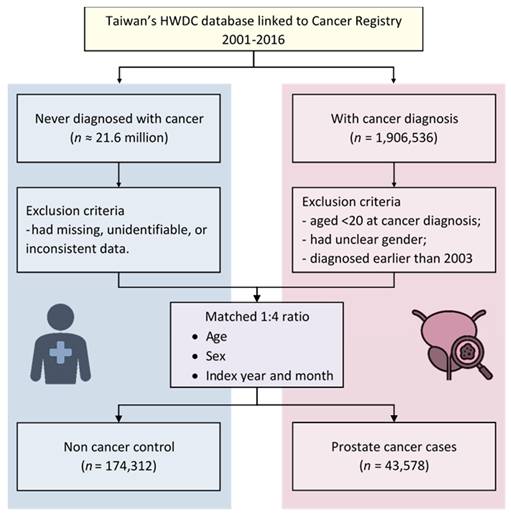

Each prostate cancer case was matched with up to four controls based on age, sex, and the index year and month, using a 1:4 matching ratio. This approach aimed to enhance statistical power and reduce potential selection bias [21]. A study flowchart outlining the methodology is presented in Figure 1.

2.3 Definition of H2RA Users

H₂RA users were identified based on outpatient and inpatient prescription records obtained from HWDC databases. Medications were classified using the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system [22], specifically under the code A02BA for H₂RAs. The index date was defined as the year and month of the first prostate cancer diagnosis for cases, and the corresponding matched year and month for controls. Individuals were categorized as H₂RA users if they had a cumulative usage of ≥ 60 days prior to the index date. This definition mirrors established claims-based definitions for sustained use [23] and follows methodological standards to prevent exposure misclassification [24]. Clinically, this cutoff distinguishes stable treatment implementation from incidental use [25].

Those who did not use any H₂RA or had cumulative use of less than 60 days were classified as non-users. For analyses of individual H₂RA drugs (cimetidine, ranitidine, and famotidine), users were identified independently for each medication, so that individuals could be classified as users of more than one H₂RA during the observation period.

2.4 Confounding Factor Adjustment

Potential confounders included comorbidities and medications associated with cancer risk. Comorbidities were assessed using diagnostic codes and summarized with the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [26, 27]. Aspirin (ATC: B01AC06) [28] and metformin (ATC: A10BA02) [29], and statins (ATC: C10AA) [30] use were included due to their known associations with cancer.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between H₂RA use and prostate cancer risk. All models were adjusted for age-adjusted CCI scores and concomitant medications. Analyses were conducted overall and stratified by age groups (20-39, 40-64, and ≥ 65 years).

3. Results

3.1 Baseline Characteristics of Cases and Controls

A total of 43,578 prostate cancer cases and 174,312 matched controls were included in the study (Figure 1). The mean age in both groups was approximately 71 years, with individuals aged 65 years and older comprising 79.22% of the study population (Table 1).

Baseline Characteristics of the Case Group and the Control Group

| Characteristics | Cases (n=43,578) | Controls (n = 174,312) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 71.18 ± 8.06 | 71.16 ± 8.01 | Matched |

| 20-39, n (%) | 16 (0.04) | 64 (0.04) | Matched |

| 40-64, n (%) | 9,041 (20.75) | 36,164 (20.75) | Matched |

| ≥ 65, n (%) | 34,521 (79.22) | 138,084 (79.22) | Matched |

| Age-adjusted CCI score, mean ± SD | 3.58 ± 2.68 | 3.31 ± 2.57 | Matched |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | |||

| AIDS/HIV | 3 (0.01) | 37 (0.02) | .048 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6,788 (15.61) | 28,286 (16.23) | .002 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 7,445 (17.12) | 26,516 (15.21) | < .001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2,140 (4.92) | 8,655 (4.97) | .707 |

| Dementia | 1,249 (2.87) | 6,672 (3.83) | < .001 |

| Diabetes | 9,062 (20.84) | 37,350 (21.43) | .008 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 216 (0.50) | 1,205 (0.69) | < .001 |

| Mild liver disease | 4,334 (9.97) | 13,996 (8.03) | < .001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 567 (1.30) | 2,660 (1.53) | < .001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 10,663 (24.52) | 32,527 (18.66) | < .001 |

| Renal disease | 3,563 (8.19) | 12,166 (6.98) | < .001 |

| Rheumatic disease | 460 (1.06) | 1,548 (0.89) | < .001 |

| Serious liver disease | 24 (0.06) | 194 (0.11) | < .001 |

| Concomitant drugs, n (%) | |||

| Aspirin | 10,964 (25.16) | 42,509 (24.39) | < .001 |

| Metformin | 8,066 (18.51) | 29,671 (17.02) | < .001 |

| Statin | 6,230 (14.30) | 27,782 (15.94) | < .001 |

SD, standard deviation

Compared to controls, cases had higher prevalence of peptic ulcer disease, chronic pulmonary disease, mild liver disease, renal disease, and rheumatic disease, at 24.52%, 17.12%, 9.97%, 8.19%, and 1.06%, respectively. Regarding concomitant medications, the use of aspirin and metformin was more common in the case group compared to the control group.

3.2 Overall Association between H2RA Use and Prostate Cancer

In Table 2, long-term use of H₂RAs (≥ 60 cumulative days) was associated with a modest but statistically significant increase in prostate cancer risk compared to non-users (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.069; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.031-1.109; p = .0004).

Flow diagram showing study design. HWDC, Health and Welfare Data Science Center.

The association of H2 receptor antagonists with the risk of prostate cancer by age groups.

| Age | 40-64 years (n = 45,205) | ≥ 65 years (n = 172,605) | Total† (n = 217,890) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | aOR | 95%CI | aOR | 95%CI | aOR | 95%CI | |

| Overall | 0.988 | (0.898, 1.087) | 1.087*** | (1.044, 1.131) | 1.069*** | (1.031, 1.109) | |

| Cimetidine | 0.865* | (0.755, 0.990) | 1.079** | (1.026, 1.135) | 1.051* | (1.002, 1.101) | |

| Ranitidine | 1.090 | (0.882, 1.347) | 1.141** | (1.044, 1.248) | 1.131** | (1.042, 1.228) | |

| Famotidine | 1.025 | (0.866, 1.212) | 1.020 | (0.943, 1.102) | 1.016 | (0.947, 1.090) | |

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.; † The "Total" category includes all participants aged ≥ 20 years, including those aged 20-39 years (n = 80); aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

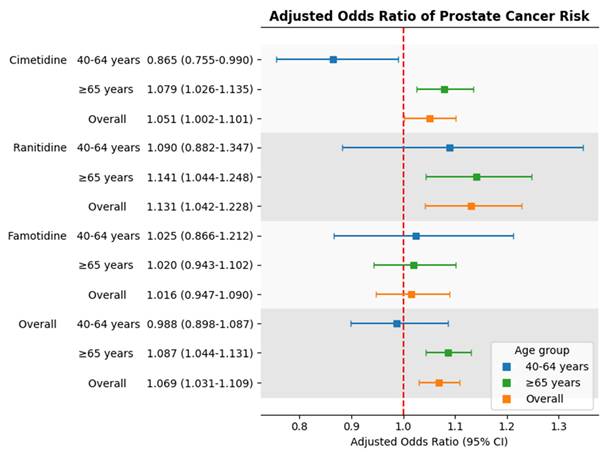

In age-stratified analysis, this association remained significant among individuals aged 65 years and older (aOR = 1.087; 95% CI: 1.044-1.131; p < .0001), but was not observed in the 40-64 age group (aOR = 0.988; 95% CI: 0.898-1.087; p = .8012).

3.3 Drug-Specific Risk Estimates

When examining individual drugs, both cimetidine and ranitidine were associated with increased prostate cancer risk in the overall population. The adjusted odds ratio for cimetidine was 1.051 (95% CI: 1.002-1.101; p < .05), and for ranitidine was 1.131 (95% CI: 1.042-1.228; p < .01). In contrast, famotidine use was not significantly associated with prostate cancer risk (aOR = 1.016; 95% CI: 0.947-1.090; p >.05).

3.4 Age-Stratified Analysis of Individual H₂RA Drugs

Among individuals aged 65 years and older, both cimetidine and ranitidine users showed a significantly increased risk of prostate cancer. The adjusted odds ratios were 1.079 (95% CI: 1.026-1.135; p =.003) for cimetidine and 1.141 (95% CI: 1.044-1.248; p =.0037) for ranitidine.

In contrast, among individuals aged 40 to 64 years, cimetidine use was associated with a statistically significant reduction in prostate cancer risk (aOR =0.865; 95% CI: 0.755-0.990; p =.0358). Ranitidine and famotidine were not significantly associated with risk in this age group. Due to data de-identification, analysis for the 20-39 age group was not possible.

3.5 Summary of Risk Estimates

Figure 2 presents a forest plot summarizing the aORs for prostate cancer risk associated with each drug across age groups. The findings show consistent increased risk for cimetidine and ranitidine in older adults, while famotidine use remained unassociated with prostate cancer in all age categories.

Adjusted odds ratios for prostate cancer risk associated with individual H2 receptor antagonists by age group. Squares represent adjusted odds ratios; horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. The red dashed line marks adjusted odds ratio = 1.0.

4. Discussion

This large-scale, population-based case-control study using claims and registry data from Taiwan's HWDC provides evidence that long-term use of H₂RAs is associated with a modest but statistically significant increase in prostate cancer risk, particularly among individuals aged 65 years and older. Stratified analyses revealed that both cimetidine and ranitidine users in this age group exhibited elevated adjusted odds ratios for prostate cancer, whereas famotidine use was not significantly associated with risk across any age category. In contrast, cimetidine use among individuals aged 40-64 years showed an inverse association; however, this finding should be interpreted cautiously given the potential for residual confounding.

Among the H₂RAs examined, cimetidine demonstrated the most distinct age-dependent pattern. The inverse association observed in middle-aged men (40-64 years) is consistent with previous studies suggesting cimetidine's anti-cancer potential [31-34], which may be attributable to its unique endocrine-modulating properties. Unlike other H₂RAs, cimetidine exhibits anti-androgenic activity by competitively inhibiting the binding of dihydrotestosterone and testosterone to androgen receptors, and by interfering with cytochrome P450-mediated sex hormone metabolism [31, 32]. Given the critical role of androgen signaling in prostate cancer development [35], partial blockade in individuals with physiologically normal androgen levels may attenuate prostatic stimulation, which might partly explain the observed inverse association.

However, the association between cimetidine use and prostate cancer risk appears to shift with age. Among older men (≥ 65 years), we observed an increased risk, potentially indicating an age-related vulnerability. Although previous studies did not specifically investigate older populations, some evidence has raised concerns about the carcinogenic potential of prolonged or high-dose cimetidine exposure [10, 11]. A cohort study reported an elevated risk among men with daily cimetidine use for over 10 years compared to nonusers [10], and animal studies have similarly suggested potential tumor-promoting effects with prolonged exposure [11]. The exact mechanisms underlying this shift remain unclear. One possible explanation for this age-related risk reversal involves age-associated hormonal decline. In older adults with naturally reduced testosterone levels [35], additional suppression of androgenic signaling induced by cimetidine may disrupt endocrine homeostasis, potentially promoting tumor progression. Specifically, such hormonal insufficiency may favor the dedifferentiation of prostate cells or the selection of androgen-independent clones, ultimately leading to more aggressive disease [4, 5, 36]. Clinical evidence supports this hypothesis: low circulating testosterone and estradiol levels are associated with a higher risk of high-grade prostate cancer [36], and chronic androgen deprivation may promote castration-resistant phenotypes through androgen receptor-related signaling involving receptor overexpression, mutations, ligand-independent activation, and bypass pathways [4, 5].

Ranitidine, in contrast, has been the subject of recent safety concerns due to NDMA contamination [12-14]. Although a pharmacovigilance study (n = 21,085) found disproportionality signals linking ranitidine to tumor-related adverse events, particularly in older adults, when compared to all other drugs in the database [37], findings from large population-based cohort studies have not supported an increased cancer risk. Nationwide cohort study from South Korea (n = 88,416) [38], Japanese (n = 113,745) [16], and a multinational cohort study involving 11 international databases [15] all reported no significant association between ranitidine use and prostate cancer risk when compared to other H₂RA users. Despite the lack of association in prior studies, we observed a modest increase in risk among older adults in our cohort. This age-specific association may reflect increased vulnerability to possible ranitidine-related degradation products, including NDMA, although the precise mechanisms remain unclear [12, 39].

Famotidine has been shown to be as effective as cimetidine and ranitidine in the treatment of acid-related disorders, with fewer side effects and no reported anti-androgenic activity [40]. Although prior studies compared famotidine with other H₂RAs [16, 41], our findings similarly showed no evidence of an association between famotidine use and prostate cancer risk across any age group when compared to non-users. This supports the possibility that specific drug-related characteristics, rather than H₂RA use as a class, may contribute to the observed associations.

Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. As with all observational studies, causality cannot be inferred, and residual confounding may persist—particularly from unmeasured lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and diet. Prescription records do not guarantee actual medication adherence and do not capture over-the-counter use. We were unable to distinguish mutually exclusive users of individual H₂RAs (e.g., only-cimetidine vs only-ranitidine), as the extracted dataset did not allow reconstruction of exclusive exposure categories, and overlapping exposure may have resulted in exposure misclassification and limited our ability to report mutually exclusive, age-specific exposure counts. Additionally, the ≥ 60-day definition was intended to reflect sustained use, it may not fully capture dose-response relationships. Furthermore, lag-time analysis to exclude exposure immediately before the index date and defined daily dose (DDD)-based dose-response evaluation could not be performed because the extracted dataset did not include segmented exposure windows or DDD information, limiting assessment of potential reverse causation and cumulative dose effects. In addition, specific clinical indications such as gastroesophageal reflux disease or peptic ulcer disease, as well as healthcare utilization measures (e.g., visit frequency or prostate cancer screening) were not available for adjustment. As a result, residual indication and detection bias cannot be fully ruled out. Finally, other H₂RAs such as roxatidine and nizatidine were excluded due to limited or unavailable use in Taiwan, restricting the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, our findings underscore the importance of evaluating both class-wide and drug-specific associations in pharmacoepidemiologic research. The differential risk patterns observed among cimetidine, ranitidine, and famotidine users highlight the necessity of considering pharmacologic mechanisms, contamination history, and patient characteristics in interpreting cancer risk signals. Given the widespread historical use of H₂RAs, particularly among older adults, continued monitoring and further drug-specific research are warranted to better inform clinical risk assessment and public health strategies.

Abbreviations

aOR: adjusted odds ratio

ATC: Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

CCI: Charlson comorbidity index

CI: confidence interval

HWDC: Health and Welfare Data Science

H₂RA: Histamine-2 receptor antagonist

IARC: International Agency for Research on Cancer

NDMA: N-nitrosodimethylamine

OR: odds ratio

TNM: tumor-node-metastasis

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research was funded by National of Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (NSTC 113-2628-B-038-007-MY3 and NSTC 113-2410-H-038-008) and the Ministry of Education.

Ethics Statement

- Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: This study was approved by the Taipei Medical University - Joint Institutional Review Board (TMU-JIRB) with the approval number N202003069.

- Informed Consent: N/A.

- Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: N/A.

- Animal Studies: N/A.

Author Contributions

Shao-Fu Wang: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing - original draft. Yu-Chen Liu: conceptualization, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing, visualization. Phung-Anh Nguyen: conceptualization, formal analysis, resources, visualization. Guan-Ling Lin: writing - review and editing. Chih-Wei Huang: conceptualization, data curation, visualization. Annisa Ristya Rahmanti: conceptualization. Hsuan-Chia Yang: conceptualization, methodology, investigation resources, data curation, writing - review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229-63

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17-48

3. Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates and Trends-An Update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):16-27

4. Tan MH, Li J, Xu HE, Melcher K, Yong EL. Androgen receptor: structure, role in prostate cancer and drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(1):3-23

5. Kumar R, Sena LA, Denmeade SR, Kachhap S. The testosterone paradox of advanced prostate cancer: mechanistic insights and clinical implications. Nat Rev Urol. 2023;20(5):265-78

6. Welen K, Damber JE. Androgens, aging, and prostate health. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2022;23(6):1221-31

7. Bergengren O, Pekala KR, Matsoukas K, Fainberg J, Mungovan SF, Bratt O. et al. 2022 Update on Prostate Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors-A Systematic Review. Eur Urol. 2023;84(2):191-206

8. Mucci LA, Hjelmborg JB, Harris JR, Czene K, Havelick DJ, Scheike T. et al. Familial Risk and Heritability of Cancer Among Twins in Nordic Countries. JAMA. 2016;315(1):68-76

9. Siltari A, Lonnerbro R, Pang K, Shiranov K, Asiimwe A, Evans-Axelsson S. et al. How Well do Polygenic Risk Scores Identify Men at High Risk for Prostate Cancer? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2023;21(2):316 e1- e11

10. Velicer CM, Dublin S, White E. Cimetidine use and the risk for prostate cancer: results from the VITAL cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(12):895-900

11. Liu X, Jia Y, Chong L, Jiang J, Yang Y, Li L. et al. Effects of oral cimetidine on the reproductive system of male rats. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15(6):4643-50

12. Braunstein LZ, Kantor ED, O'Connell K, Hudspeth AJ, Wu Q, Zenzola N. et al. Analysis of Ranitidine-Associated N-Nitrosodimethylamine Production Under Simulated Physiologic Conditions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034766

13. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Laboratory analysis of ranitidine and nizatidine products. 2020 [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/laboratory-tests-ranitidine]

14. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Requests Removal of All Ranitidine Products (Zantac) from the Market: U. S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020 [Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-requests-removal-all-ranitidine-products-zantac-market]

15. You SC, Seo SI, Falconer T, Yanover C, Duarte-Salles T, Seager S. et al. Ranitidine Use and Incident Cancer in a Multinational Cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(9):e2333495

16. Iwagami M, Kumazawa R, Miyamoto Y, Ito Y, Ishimaru M, Morita K. et al. Risk of Cancer in Association with Ranitidine and Nizatidine vs Other H2 Blockers: Analysis of the Japan Medical Data Center Claims Database 2005-2018. Drug Saf. 2021;44(3):361-71

17. Wang CH, Chen, II, Chen CH, Tseng YT. Pharmacoepidemiological Research on N-Nitrosodimethylamine-Contaminated Ranitidine Use and Long-Term Cancer Risk: A Population-Based Longitudinal Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12469

18. Cardwell CR, McDowell RD, Hughes CM, Hicks B, Murchie P. Exposure to Ranitidine and Risk of Bladder Cancer: A Nested Case-Control Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(8):1612-9

19. Hsieh CY, Su CC, Shao SC, Sung SF, Lin SJ, Kao Yang YH. et al. Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database: past and future. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:349-58

20. National Health Insurance Administration. Universal health coverage in Taiwan. Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2025 [Available from: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/ch/mp-1.html]

21. Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Compared to what? Finding controls for case-control studies. Lancet. 2005;365(9468):1429-33

22. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. ATC/DDD Index 2025 Oslo, Norway: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; 2024 [Available from: https://atcddd.fhi.no/atc_ddd_index/]

23. Nguyen NTH, Huang CW, Wang CH, Lin MC, Hsu JC, Hsu MH. et al. Association between Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and the Risk of Female Cancers: A Nested Case-Control Study of 23 Million Individuals. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(24):6083

24. Pottegård A, Hallas J. Assigning exposure duration to single prescriptions by use of the waiting time distribution. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2013;22(8):803-9

25. Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T. et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691-705

26. Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, Patierno C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91(1):8-35

27. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-83

28. Cao Y, Nishihara R, Wu K, Wang M, Ogino S, Willett WC. et al. Population-wide Impact of Long-term Use of Aspirin and the Risk for Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(6):762-9

29. Rothwell PM, Fowkes FG, Belch JF, Ogawa H, Warlow CP, Meade TW. Effect of daily aspirin on long-term risk of death due to cancer: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377(9759):31-41

30. Hou YC, Shao YH. The Effects of Statins on Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Androgen Deprivation Therapy or Definitive Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15(2):131

31. Kubecova M, Kolostova K, Pinterova D, Kacprzak G, Bobek V. Cimetidine: an anticancer drug? Eur J Pharm Sci. 2011;42(5):439-44

32. Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, Sukhatme V, Sukhatme VP. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)-cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485

33. Jafarzadeh A, Nemati M, Khorramdelazad H, Hassan ZM. Immunomodulatory properties of cimetidine: Its therapeutic potentials for treatment of immune-related diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;70:156-66

34. Beltrame FL, Cerri PS, Sasso-Cerri E. Cimetidine-induced Leydig cell apoptosis and reduced EG-VEGF (PK-1) immunoexpression in rats: Evidence for the testicular vasculature atrophy. Reprod Toxicol. 2015;57:50-8

35. Cheng H, Zhang X, Li Y, Cao D, Luo C, Zhang Q. et al. Age-related testosterone decline: mechanisms and intervention strategies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2024;22(1):144

36. Salonia A, Abdollah F, Capitanio U, Suardi N, Briganti A, Gallina A. et al. Serum sex steroids depict a nonlinear u-shaped association with high-risk prostate cancer at radical prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(13):3648-57

37. Liu M, Luo D, Jiang J, Shao Y, Dai D, Hou Y. et al. Adverse tumor events induced by ranitidine: an analysis based on the FAERS database. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2025;24(1):35-47

38. Yoon HJ, Kim JH, Seo GH, Park H. Risk of Cancer Following the Use of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Contaminated Ranitidine Products: A Nationwide Cohort Study in South Korea. J Clin Med. 2021;10(1):153

39. Kang DW, Kim JH, Choi GW, Cho SJ, Cho HY. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for evaluating gender-specific exposures of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA). Arch Toxicol. 2024;98(3):821-35

40. Humphries T. Famotidine: a notable lack of drug interactions. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1987;22(sup134):55-60

41. Kim YD, Wang J, Shibli F, Poels KE, Ganocy SJ, Fass R. No association between chronic use of ranitidine, compared with omeprazole or famotidine, and gastrointestinal malignancies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54(5):606-15

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Hsuan-Chia Yang, College of Medical Science and Technology, Graduate Institute of Biomedical Informatics, Taipei Medical University, Shuangho Campus, Teaching & Research Building, 9F, No. 301, Yuantong Rd., Zhonghe Dist., New Taipei City 235, Taiwan. Email: lovejogedu.tw; itpharmacistcom.

Corresponding author: Hsuan-Chia Yang, College of Medical Science and Technology, Graduate Institute of Biomedical Informatics, Taipei Medical University, Shuangho Campus, Teaching & Research Building, 9F, No. 301, Yuantong Rd., Zhonghe Dist., New Taipei City 235, Taiwan. Email: lovejogedu.tw; itpharmacistcom.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact