Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2026; 17(2):300-315. doi:10.7150/jca.125305 This issue Cite

Review

Role and Molecular Mechanisms of Aerobic Glycolysis in Gastrointestinal Tumors

1. Department of Oncology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China.

2. Department of Bone and Joint Surgery, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China.

3. Department of Oncology, The Xichang People's Hospital, Xichang, China.

4. Department of Cardiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China.

5. Department of Pathology, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, China.

6. Department of Oncology, Hejiang County People's Hospital, Luzhou, China.

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-9-16; Accepted 2025-12-12; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Gastrointestinal tumors are among the most common tumors worldwide and are currently the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Gastrointestinal tumors affect the digestive system and include esophageal, liver, gastric, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers. Aerobic glycolysis is a widespread phenomenon among gastrointestinal tumor cells, which poses a major hazard to human health and life. Increasing evidence suggests that aerobic glycolysis can induce and promote the development of gastrointestinal tumors by rapidly providing large amounts of energy and altering the tumor microenvironment. Among them, glucose transporter proteins and key enzymes involved in glycolysis are expressed at higher levels during aerobic glycolysis, and the corresponding signaling pathways and transcription regulatory factors are activated, playing an important role in the occurrence and development of tumors. Additionally, evidence has indicated that aerobic glycolysis plays an essential role in inhibiting the development of immune cells, modifying the population of immune cells present in the surrounding tumor, and promoting the polarization of immune cells. Moreover, drugs and compounds that target essential enzymes and transcription factors associated with glycolysis are known to exhibit anticancer properties.

Keywords: aerobic glycolysis, Warburg effect, gastrointestinal tumors, immune cells, tumor microenvironment

1. Background

Gastrointestinal tumors have a high incidence in the general population and are frequently identified in the later stages of development, with unfavorable prognoses and increased mortality rates. Aerobic glycolysis is a prevalent biological and chemical process in gastrointestinal tumors. Even in the presence of sufficient oxygen, tumor cells prefer to use glycolysis as their primary energy source, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect [1]. Professor Warburg first identified aerobic glycolysis approximately 100 years ago as a marker of hepatocellular carcinoma in rats [1]. An increased intake of glucose is a hallmark of aerobic glycolysis, resulting in increased production of intermediates and lactic acid, which provides more adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to tumor cells [2]. The accumulation of lactic acid and intermediate products provides a conducive microenvironment for the growth and spread of tumors [3]. Glycolysis-related enzymes play an important role in tumor development. Owing to the disparity in glucose absorption rates between malignant and healthy cells, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) can be used to diagnose cancer and monitor its progress [4]. Glycolysis also promotes tumor invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, drug resistance, and immune evasion [5]. Therefore, aerobic glycolysis plays a crucial role in tumor formation and progression. A comprehensive understanding of the function of aerobic glycolysis in the context of cancer will contribute to future research on targeted therapies. In this article, we discuss the contribution of aerobic glycolysis to the development and progression of gastrointestinal tumors and the underlying mechanisms, including current targeted therapies for aerobic glycolysis.

2. Changes in glucose metabolism in gastrointestinal tumors

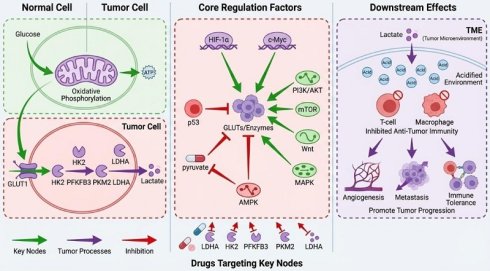

Aerobic glycolysis is widely considered a key process in tumor growth, mainly because it can rapidly provide energy for tumor cells to grow and proliferate [6] and alter metabolism in the tumor microenvironment [7] thus facilitating suitable conditions for tumor recurrence, metastasis [8], and immune tolerance [9]. The multiple biological functions of aerobic glycolysis and its products are gradually being discovered.

2.1 Role of glucose transporters in gastrointestinal tumors

Aerobic glycolysis in tumors is an energy-intensive process that requires large amounts of glucose for growth, proliferation, and metastasis. Thus, the rate of glucose uptake via glucose transporters is enhanced to support accelerated metabolism in malignant cells.

Glucose transporter proteins (GLUTs) mediate the initial and most significant step in glucose metabolism, namely the transport of glucose across the plasma membrane in mammalian cells [10]. The glucose transporter family comprises 14 proteins that can be divided into three classes based on sequence similarity: class I (GLUTs 1-4, 14), class II (GLUTs 5, 7, 9, and 11), and class III (GLUTs 6, 8, 10, 12, and 13/HMIT). The augmented glucose transport observed in cancerous cells is often linked to the upregulated and dysregulated expression of glucose transporters, with the overexpression of GLUT1 and/or GLUT3 being a typical feature [11]. Hypoxic tumor cells upregulate the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1), which plays a pivotal role in mediating the transcriptional regulation of glycolytic genes that carry hypoxia response elements in their promoters, including the glucose transporter proteins GLUT1 and GLUT3 [12]. The glucose transporter protein GLUT1 is considered the founding member of the GLUT family and enables glucose transport across the hydrophobic cell membrane without requiring energy, thereby reducing the concentration gradient [13]. HIF-1 stimulates the expression of GLUT1, which is strongly affinitive to glucose and can transport galactose, mannose, glucosamine, and dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) to promote tumor cell proliferation [14]. Moreover, GLUT1 expression is directly associated with tumorigenesis and metastasis [15]. Similar to GLUT1, GLUT3 has a strong ability to bind and transport glucose molecules. In addition to glucose, GLUT3 is capable of transporting other molecules such as galactose, mannose, maltose, xylose, and DHA. Tumors with a high glucose demand may utilize GLUT3 as an effective means to enhance glucose uptake into their cells owing to its strong affinity for glucose, ultimately promoting tumor cell proliferation [16]. This overexpression has been repeatedly reported in almost all cancer types, suggesting that glucose transporters contribute significantly to cancer cell proliferation and growth. Moreover, the p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway stimulates the use of glucose as an energy source in gastric cancer cells by facilitating the transport of glucose into cells via an increase in the expression of the GLUT4 transporter [17]. In colon cancer cells, activation of AKT1 and AKT3 results in the abnormal suppression of miR-125b-5p, which subsequently leads to the upregulation of GLUT5 expression, causing metastasis and drug resistance in colon cancer cells [18]. In pancreatic cancer, increased GLUT1 expression is significantly correlated with poorer prognosis, larger tumor size, and lymph node metastasis [19].

2.2 Glycolysis produces ATP for tumor cells

Glucose is metabolized by tumor cells in two ways. First, when oxygen is sufficient, glucose generates pyruvate in the cytoplasm, which enters the mitochondria for oxidative phosphorylation, where it is finally metabolized into carbon dioxide and water, releasing a large amount of energy [20]. Second, the conversion of pyruvate to lactate is facilitated by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase in the cytoplasm under hypoxic conditions [21] (Figure 1).

Glycolysis generates a significant quantity of lactic acid that builds up in the tumor microenvironment to form an acidic environment and reduce the pH of the microenvironment [22]. The resulting acidic microenvironment promotes tumor growth and metastasis [23], angiogenesis [24], and immunosuppression [25]. In particular, lactic acid-induced GPR81 activation promotes tumor growth [26]. Lactic acid promotes tumor metastasis and invasion by remodeling the extracellular matrix, increasing cell activity, and enhancing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [27]. Lactic acid promotes angiogenesis by stimulating macrophages to secrete vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF), enhancing endothelial cell migration and vascular morphogenesis, and recruiting circulating vascular precursor cells [28]. Lactic acid can upregulate inhibitory molecules, produce immunosuppressive cytokines, and downregulate costimulatory molecules to induce immune tolerance in tumors [29].

The swift multiplication and dissemination of cancerous cells throughout the body require an abundant and rapid supply of ATP, which is generated by aerobic glycolysis in tumor cells [30]. The regulation of aerobic glycolysis is influenced by three critical enzymes: hexokinase (HK), phosphofructokinase (PFK), and pyruvate kinase (PK), and the equilibrium enzyme fructose-bisphosphatase [31]. The rate of tumor growth and proliferation, along with prognosis, is influenced by changes in the function or expression of these enzymes or isozymes.

2.2.1 Hexokinase

HK is the initial bottleneck enzyme in the glycolytic pathway, irreversibly catalyzing the conversion of glucose into glucose-6-phosphate, and exists in the human body mainly as four isozymes: HK1, HK2, HK3, and HK4. There is significant upregulation of HK2 expression in many malignancies, and its high expression is associated with cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, recurrence, and poor prognosis [32]. Multiple studies indicate that elevated HK2 expression is associated with resistance to radiotherapy [33].

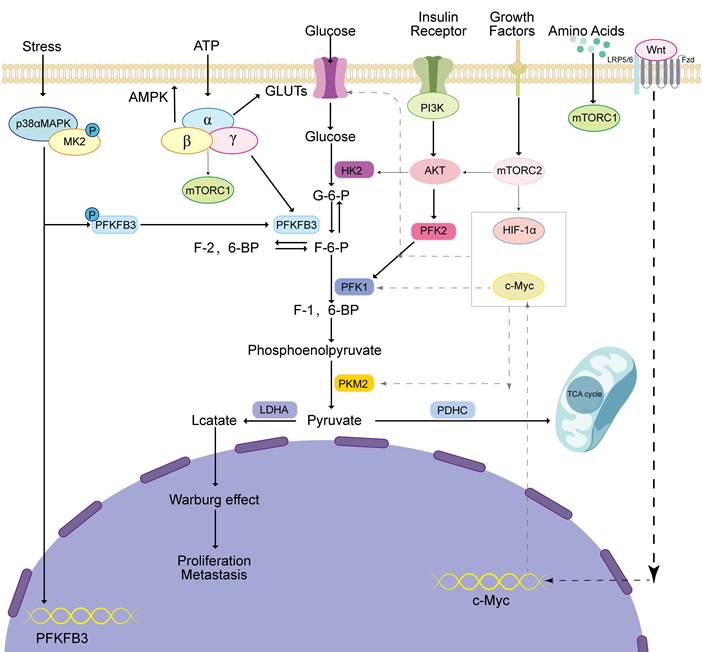

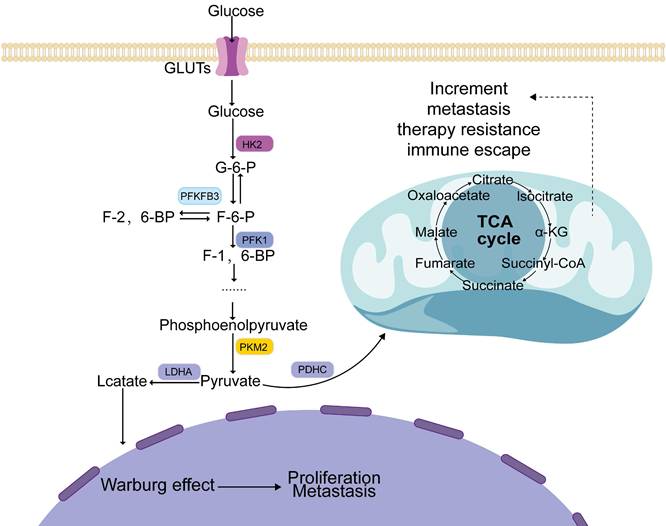

Metabolism of glucose in tumor cells involves several steps. Firstly, glucose is taken into the cells by GLUT and then transformed by key glycolytic enzymes such as HK2, PFKFB3, PFK1, and PKM2. This transformation generates pyruvate, which is eventually converted into lactate by LDHA. This process of lactate production promotes the Warburg effect, which ultimately aids tumor progression. Simultaneously, if pyruvate is prevented from entering the mitochondria and participating in the TCA cycle, it can cause mitochondrial dysfunction and further promote tumor development.

HK domain-containing 1 (HKDC1), which is significantly elevated in hepatocellular carcinoma, stimulates the multiplication and migration of malignant liver cells by upregulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [34]. In gastric cancer, mesenchymal stem cells exhibit a G6PD-NF-KB-HGF signaling pathway that promotes growth and spread [35]. HK2 is also involved in apoptosis and autophagy. For example, mitochondrial membrane stability is promoted by the interaction between HK2 and voltage-dependent anion channels located in the mitochondria, which prevents the binding of pro-apoptotic factors, thereby inhibiting apoptosis [36]. HK2 can stimulate autophagy under glucose-depleted conditions and glycolytic activity even when adequate glucose is present; thus, HK2 can switch between autophagy and glycolysis depending on the amount of glucose [37].

2.2.2 Phosphofructokinase

PFK1 plays a pivotal role as the second rate-controlling enzyme in the glycolytic pathway, irreversibly facilitating the transformation of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate by utilizing ATP as a co-substrate [38]. The human body contains three different isoforms of PFK1, PFKM in the muscles, PFKL in the liver, and PFKP in the blood, in different proportions in different tissues. PFK1 is inhibited by the negative feedback activity of its downstream products, which regulate the pace of the glycolytic pathway through their controlling actions, including the production of phosphoenolpyruvate, lactate, citrate, and ATP [39]. Notably, 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) catalyzes the conversion of fructose-6-phosphate (F-6-P) to fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (F-2,6-BP), the strongest metabotropic stimulator of PFK1 with the highest potency [40] which significantly increases the activity of PFK1 and enhances glycolysis. PFK2 and PFKFB can control the levels of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate through their regulatory functions [41], which is important for regulating glycolysis, cell proliferation, and metastasis.

PFK is widely expressed in gastrointestinal tumors. Overexpression of PFKFB3 causes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by increasing the expression of Snail and Twist, which enhances the migration and invasion abilities of gastric cancer cells [42]. Human colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma tissues exhibit significant PFKFB3 expression, and its overexpression has been linked to lymph node metastasis, intravascular cancer thrombosis, and TNM staging in patients with sporadic colorectal cancer [43]. The expression of PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 is detectable in pancreatic cancer cells, which display a significant hypoxia-induced response mediated by HIF-1 [44].

2.2.3 Pyruvate kinase

PK regulates the last step of glycolysis by irreversibly converting phosphoenolpyruvate into pyruvate, thereby controlling the rate at which glucose is metabolized to produce energy. PK consists of four isomers: hepatic PKL, blood PKR, muscle PKM1, and PKM2. PKM2 is significantly more highly expressed in malignant tumors [45] and facilitates the transformation of phosphoenolpyruvate into pyruvate, generating ATP, thus increasing the rate of glycolysis [46]. PKM2 enters the nucleus and promotes the conversion of DNA into RNA molecules for specific genes, leading to positive feedback regulation of glycolysis [47]. PKM2 enhances tumor cell growth and hinders autophagy via the JAK/STAT3 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma [48]. In addition, PKM2 facilitates the formation of new blood vessels in tumors by modulating HIF-1, ultimately leading to the activation of NF-κB [49]. Cross-talk between the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)/PKM2 and STAT3/c-myc signaling pathways modulates the acid-base balance of the microenvironment and the metabolic state in gastric cancer [50].

2.3 Aerobic glycolysis-related key signaling pathways

Several signaling pathways contribute significantly to the development and progression of tumors [51], metastatic recurrence [52], development of drug resistance [53], and EMT [54]. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [55], phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) [56], mTOR [57], MAPK [58], and Wnt [59] signaling pathways can affect aerobic glycolysis in tumor cells (Figure 2).

2.3.1 AMPK pathway

AMPK, a protein kinase that phosphorylates serine/threonine residues, shows a high degree of evolutionary conservation and acts as a sensor to maintain energy homeostasis [60]. AMPK is composed of three subunits, with a catalytic α subunit and a regulatory β/γ subunit forming a heterotrimeric complex. AMPK can directly sense the AMP:ATP ratio and is rapidly activated when ATP levels are reduced, as in the case of glucose starvation [61], metabolic inhibition [62], or muscle contraction [63]. Recent studies have demonstrated that AMPK mediates the suppression of tumor cell growth [64].

AMPK directly inhibits mTORC1 activity by phosphorylating TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex 2) [65] and RAPTOR (a subunit of mTORC1) [66]. mTORC1 is a critical regulator of cell growth and protein synthesis, and its overactivation is closely linked to the development of various cancers. By inhibiting mTORC1, AMPK reduces tumor cell proliferation and survival. AMPK activates multiple tumor suppressor proteins, such as p53, p27, and pRb, which play key roles in inducing cell cycle arrest [67]. In addition to regulating the cell cycle, AMPK also activates ULK1 (Unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1), a critical regulator of autophagy [68]. Moreover, under conditions of glucose deficiency, AMPK collaborates with the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway to phosphorylate and inactivate YAP (Yes-associated protein) [69]. Moreover, since abnormal activation of the hedgehog pathway is implicated in the development of many cancers, AMPK targeting of GLI1 reduces hedgehog signaling, further contributing to the suppression of tumor cell proliferation [70].

Furthermore, AMPK hinders the tumorigenesis of esophageal cancer via an AMPK/FOXO3a/BIM-dependent mechanism [71]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, AMPK promotes the degradation of HIF-1α via the autophagy-lysosome pathway involving AMPK/ULK1 [72].

2.3.2 PI3K/AKT pathway

The PI3K/AKT pathway induces glucose metabolism in tumors. Phosphorylation of intracellular inositol lipids by PI3Ks enables them to function as lipid kinases that regulate signaling and intracellular vesicle transport. PI3Ks can be categorized into three distinct groups based on their substrate specificity and structural characteristics. The main function of Class I PI3Ks is to generate 3-phosphatidylinositol lipids, which act as signaling molecules to directly activate downstream signal transduction pathways, whereas Class II PI3Ks govern a range of cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, primary cilia function, glucose consumption, survival, and angiogenesis. Class III PI3Ks are crucial for autophagy, endosomal transport, and phagocytosis. The enzyme AKT is a serine/threonine kinase that exists in three forms, termed isoforms, namely AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3. It is a crucial downstream effector of the PI3K signaling pathway and is involved in various essential cellular processes such as cancer cell viability, cell cycle initiation, and glucose consumption [73].

Regulation of the main pathways of aerobic glycolysis. MAPK, AMPK, PI3K, mTORC, and Wnt pathways regulate aerobic glycolysis and promote tumor occurrence and development through the expression of glucose transporters, glycolytic key enzymes, and transcription factors.

AKT is directly activated by PI3K [74]. The phosphorylation of AKT downstream of PI3K activates PFK2, which stimulates the synthesis of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, the primary agonist of PFK1, and enhances glycolysis [75]. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway promotes an increase in GLUT1 expression [76], and the PI3K/AKT pathway can facilitate the transport of this molecule from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane [77]. Activation of the insulin receptor substrate-2 stimulates the PI3K/AKT pathway and insulin-sensitive GLUT4 in the plasma membrane to promote glucose uptake, thus transactivating insulin action [78]. Therefore, the activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway can increase the levels of specific enzymes and transporters that play a role in glycolysis.

In liver cancer, the upregulation of microRNA-17-5p can decrease PTEN gene expression [79], which is a significant inhibitor of the PI3K/AKT pathway [80], thereby activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and promoting glycolysis. In colon cancer, the PI3K/AKT pathway activates mTOR and regulates the expression of downstream targets 4EBP1 and p70S6K, thus promoting the expression of genes that facilitate the cell cycle [81]. During angiogenesis in colon cancer, the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway can be triggered by various signals [82], including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and oversees critical phases by modifying certain downstream proteins through the addition of phosphate groups to promote angiogenesis [83]. In gastric cancer, PDZK1 deficiency leads to the activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which is linked to unfavorable patient outcomes [84]. In addition, activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway prompts gastric cancer cells to acquire traits resembling those of stem cells [85]. Therefore, targeting the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway has gained considerable interest as a potential therapeutic strategy.

2.3.3 mTOR pathway

mTOR plays a crucial role in helping cells progress through different stages of their life cycle, divide to form new cells, regulate cell survival and metabolism, and control the cytoskeleton in response to amino acids, stress, oxidative stress, energy demands, and growth factors. The mTOR kinase family is composed of three main parts: mTOR1, mTOR2, and mTOR3, of which both mTOR1 and mTOR2 have been linked to cancer [86].

mTORC1 is a group of proteins that work together, including Raptor, PRAS40, mLST8 (or GβL), and Deptor, all of which help regulate the activity of mTOR [87]. By activating mTORC1, cells can shift their glucose metabolism from the ordinary oxidative phosphorylation pathway to glycolysis, thus facilitating cellular proliferation and growth, while enhancing the levels of HIF1α expression [88]. mTORC1 also induces the pentose phosphate pathway, as well as the biosynthesis of sterols and lipids, and regulates the expression of G6PD [89]. In addition, mTORC2 plays a role in reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton and promoting cell migration; its activity is not affected by rapamycin [90], and its role in protein synthesis, protein maturation, autophagy, and metabolic regulation has been noted [90].

In hepatocellular carcinoma, mTORC1 downregulates the expression of NEAT1/2 and inhibits NEAT1/2-mediated biogenesis of paranuclear spots, thereby promoting mRNA splicing and the expression of critical glycolytic enzymes. Moreover, mTORC1 signaling is involved in aberrant metabolism, hepatocarcinogenesis, and the response to mTORC1-targeted therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma [91]. Colorectal cancer often involves dysregulation of the mTOR pathway, leading to activation of the AKT/mTOR axis and increased expression of c-Myc and HIF-1α; the former promotes glycolysis, and the latter accelerates the metabolic rate in colon cancer cells [92]. In addition, mTOR can increase glutamine flux, and thus glutaminase activity, by upregulating c-myc [93]. Through this pathway, oncogenic AKT and mTOR trigger protein synthesis to stimulate the expansion and reproduction of colorectal cancer cells while inhibiting the apoptosis of cancer cells. In esophageal cancer, abnormal activation of the mTOR pathway upregulates the production of HIF-1α, accelerates cellular metabolism, and increases the expression of PKM2, which induces aerobic glycolysis [94]. Therefore, the mTOR pathway is essential for aerobic glycolysis in gastrointestinal tumors.

2.3.4 MAPK pathway

The MAPK pathway is among the earliest identified intracellular signaling pathways and is involved in the evolution of multiple physiological processes. The MAPK pathway is involved in the cellular metabolic shifts during tumorigenesis. The MAPK family includes ERK, JNK, and p38-MAPK, which regulate the transcription of immediate early genes (IEGs) in response to cellular stress [95]. When MAPK is activated, the phosphorylated p38α-MAPK forms a complex with MAPK-MK2 to promote transcription, protein synthesis, cellular receptor expression, and cytoskeletal changes, thereby altering cell survival and apoptosis [96]. A recent study has indicated that PFKFB3 is an important target of MAPK-MK2; therefore, the MAPK pathway may affect glycolysis [97].

p38, PFKFB3 phosphorylates MK2 at Thr334, leading to transcription and direct activation of PFKFB3. MK2 increases PFKFB3 transcription by promoting the phosphorylation of Ser103 in SRF, which activates SRE in the promoter region of PFKFB3. In addition, phosphorylated MK2 promotes direct phosphorylation of PFKFB3 at Ser461, leading to increased PFKFB3 function and formation of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, which triggers PFK1 metabotropic activation, thus enhancing the rate of glycolysis [97].

In hepatocellular carcinoma, the extracellular matrix regulates YAP by affecting the MAPK signaling pathway, which contributes to the reprogramming of cancer metabolism [98], including glycolysis, and increased expression of YAP strengthens aerobic glycolysis and the migration of tumor cells [99]. In addition, by modulating the MAPK/ERK pathway, the hypoxia-induced lncRNA NPSR1-AS1 promotes both proliferation and glycolysis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells [58].

2.3.5 Wnt pathway

The Wnt signaling pathway is a biological mechanism that has remained unchanged throughout the course of evolution and plays a key role in embryonic development, stem cell maintenance, and wound healing. The Wnt signaling pathway is divided into a β-linked protein-dependent pathway (typical pathway) and a non-β-linked protein-dependent pathway (atypical pathway). Even though the two pathways have similarities, the non-classical pathway has not been extensively studied, and research has mostly focused on the classical pathway, which has β-linked protein as the main effector. Wnt proteins control a variety of cellular functions and activities, including cell multiplication, differentiation, movement, and the generation of new stem cells. The development of several types of cancer is linked to dysregulation of the Wnt signaling pathway. Studies have demonstrated various functional effects of oncogenic Wnt signaling, including increased proliferation, induction of EMT, promotion of angiogenesis and migration, and enhanced cell survival.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling raises glucose uptake and inhibits mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [100]. Wnt upregulates the expression of pyruvate carboxylase, an enzyme that converts pyruvate to oxaloacetate, to promote cancer cell proliferation [100]. Wnt5B, a ligand of Wnt, regulates c-Myc, which negatively affects mitochondrial function [101], and positively correlated with MCL1, a mitochondrial regulator [102]. c-Myc plays a crucial role in regulating cancer cell metabolism, particularly in aerobic glycolysis, and also acts as a transcription factor that mediates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway's control over this process [103].

In gastric cancer, the tumor cells exhibit elevated levels of LRP5 expression, and high expression of LRP5 increases the energy supply to tumor cells by triggering the typical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and increasing aerobic glycolysis by upregulating it [104]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, autophagy promotes glucose uptake and lactate production by upregulating the expression of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling [59].

2.4 Transcriptional regulation of glucose metabolism

Transcription factors are essential signal transduction components that are involved in cellular gene expression. They recognize specific DNA sequences and bind to specific response elements located in genomic regions responsible for promoting or enhancing gene expression. Transcription factors are considered the end effectors of cellular signaling pathways. Notably, transcription factors are essential for modulating the Warburg effect, and several examples of transcription factors that regulate glycolysis are listed in Table 1.

Transcription factors HIF-1, c-Myc, and p53 regulate the role of glycolytic enzymes in cancer

| Transcription factors | Expression in cancer | Target | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIF-1 | Positive | GLUT1 GLUT3 | Up-regulate Up-regulate | [10,12,109] [10,12,109] |

| c-Myc | Positive | GLUTs HK2 PFKM ENO1 PDK1 PKM2 | Up-regulate Up-regulate Up-regulate Up-regulate Up-regulate Up-regulate | [111,114] [111] [111] [111] [112] [114] |

| p53 | Negative | GLUT1 GLUT3 GLUT4 PKM2 MCT1 TIGAR | Down-regulate Down-regulate Down-regulate Down-regulate Down-regulate Down-regulate | [117,119,127] [118] [117,120] [121] [122] [124,126,127,129] |

2.4.1 HIF-1

Activation of HIF-1 increases with tumor growth [105]. GLUTs [106] and other glycolytic enzymes [107] are upregulated by HIF-1 either directly or indirectly, thereby promoting tumor cell proliferation. Other stimuli, such as insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1, epidermal growth factor, and angiotensin II, have also been shown to increase HIF-1 levels in cells [108].

The initial stage of glucose metabolism in mammalian cells is plasma membrane glucose transport, which is controlled by GLUT and serves as a major rate-limiting factor [109]. A typical feature of malignant cells is an increase in glucose transport caused by dysregulated expression of glucose transporters. Overexpression of GLUT1 and/or GLUT3 is common in these types of cells [109]. In hypoxic tumor cells, HIF-1 expression is increased, which mediates the transcriptional regulation of genes related to glycolysis that have hypoxia response elements in their promoters, such as GLUT1 and GLUT3 [110].

2.4.2 c-Myc

c-Myc is a helix-loop leucine zipper transcription factor that binds the chaperone protein Max dimer to specific DNA sequences, thereby activating genes in trans. It regulates various cellular functions, including cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, protein synthesis, cell adhesion, and energy metabolism.

c-Myc directly regulates key enzymes and GLUTs involved in glycolysis, most notably GLUT1, HK2, PFKM, and enolase 1 (ENO1) [111]. Therefore, gene expression can be promoted by c-Myc, which increases glucose transport, the catabolism of monosaccharides, and pyruvate, and their conversion to lactate. Under normoxic conditions, c-Myc promotes glucose oxidation and lactate production. However, under hypoxic conditions, c-Myc synergistically induces pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) with HIF-1, thereby inhibiting mitochondrial respiration and facilitating the transformation of glucose into lactate [112].

In pancreatic cancer, activation of c-Myc-lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) stimulates glucose utilization, lactate production, proliferation, migration, and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells [113]. In colorectal cancer, increased expression of LDHA, PKM2, and GLUT1, associated with glycolysis, was observed in c-Myc-overexpressing HCT116 cells, and the ECAR assay showed that the interference of far upstream element-binding protein 1 was reversed by c-Myc overexpression, resulting in the inhibition of glycolysis [114]. The expression of c-Myc is remarkably high in gastric cancer, and its binding to the promoter of PDK1 regulates the expression of PDK1, which inhibits PDH activity by phosphorylating PDH, thereby reducing pyruvate conversion into acetyl coenzyme A in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. This reduces mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, thus promoting pyruvate conversion into lactate, promoting aerobic glycolysis in gastric cancer cells, and reducing the pH of the tumor microenvironment via aerobic glycolysis by LDHA [115].

2.4.3 p53

p53 acts as a tumor suppressor and regulates key cellular processes such as proliferation, invasion, metastasis, apoptosis, stemness, metabolic reprogramming, cell cycle arrest, and DNA repair. Glucose metabolism in cancer cells is impacted by the activation of p53, which hinders the growth of a highly aggressive tumor phenotype [116].

p53 is involved in several glycolytic processes; it can inhibit glucose transport by directly suppressing the transcription of GLUT1 and GLUT4 [117] and can also repress NF-κB, leading to a decrease in GLUT3 expression [118]. In addition, the direct induction of ras-related glycolysis inhibitors and calcium channel regulators (RRAD) can hinder the translocation of GLUT1 to the plasma membrane by inhibiting glucose transport [119]. p53 inhibits glycolysis by indirectly repressing GLUT4 expression, and indirectly inhibits glucose uptake by repressing the insulin receptor promoter (INSR) [120] and downregulating insulin receptor expression. Furthermore, p53 upregulates parkin, which ubiquitinates PKM2 and decreases glycolytic rates [121]. It also inhibits MCT1 by repressing lactate transport, which leads to lactate accumulation and reduced glycolysis in cancer cells [122]. In addition, p53 downregulates pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 2 and upregulates parkin, resulting in increased PDH activity [123]. p53 induces the production of TIGAR, which dephosphorylates F-2,6-P2 to F6P [124]. F-2,6-P2 is a strong transactivator of PFK1. Therefore, TIGAR inhibits glycolysis. P53 also affects glycolysis by downregulating HK2 at the transcriptional level and participating in the degradation of phosphoglycerate during metastasis [125]. Taken together, these findings show that the activation of p53 can aid in reversing the Warburg effect [126].

In colon cancer cells, IC261 reduced the expression of p53 and TIGAR, upregulated GLUT1 mRNA expression, and promoted aerobic glycolysis [127]. In pancreatic cancer cells, missense mutations in p53 prevent the nuclear translocation of the glycolytic enzyme 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and stabilize its cytoplasmic localization, thus encouraging glycolysis in cancerous cells and obstructing apoptosis mediated by nuclear GAPDH [128]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, TIGAR and SCO2 transcription is controlled by TCF19 and p53, which enhance energy production and increase resistance to stress by improving mitochondrial function [129].

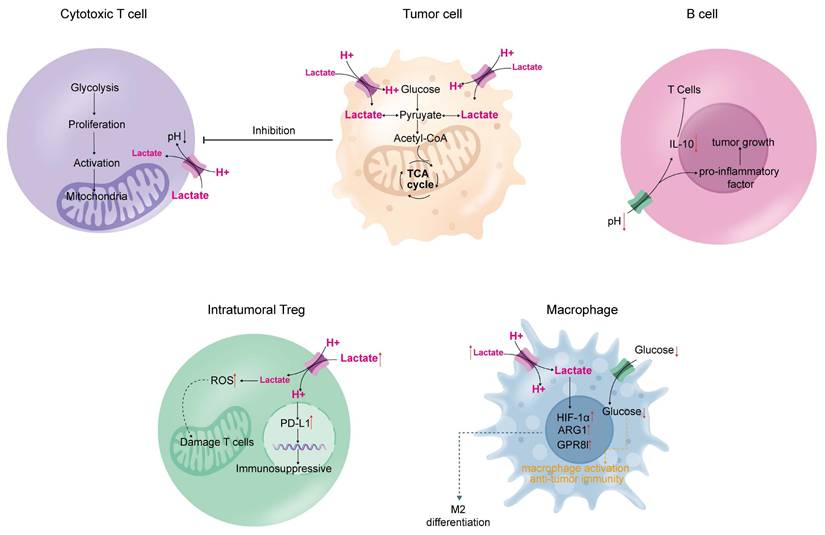

Impact of the tumor microenvironment on immune cells. Tumor cells produce a large amount of lactate through aerobic glycolysis, which is released into the microenvironment and affects the lactate concentration gradient inside immune cells. This inhibits the normal immune functions of cytotoxic T cells, macrophages, B cells, and intratumoral T cells, leading to immune deficiency in tumors, ultimately resulting in tumor progression.

3. Glycolysis mediates cancer immunity

Aerobic glycolysis in tumors leads to metabolic alterations that can impair immune function [130]. This involves three main mechanisms: (1) tumor cells compete for nutrients with growing and activated immune cells during proliferation; (2) byproducts of aerobic glycolysis in tumor cells inhibit the function of immune cells and modulate immune performance; and (3) genes and signaling pathways that regulate glycolysis produce factors and metabolites associated with immune suppression (Figure 3).

3.1 T-cell

Large amounts of lactate from aerobic glycolysis are released into the tumor microenvironment, creating a concentration gradient that prevents T cells within the microenvironment from releasing the lactate produced during their activation and proliferation [131]. High lactate levels in T cells inhibit their growth and activation [132].

Acidity, hypoxia, and lack of nutrients are distinguishing features of the tumor metabolic environment, which hinder T cells from exerting effective anti-tumor immunity and developing long-term immune memory [130]. The build-up of lactic acid in the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis has been shown to hinder T-cell mobility [133], and this phenomenon can be observed in tumors. In addition, T cell adaptation to the tumor microenvironment may lead to mitochondrial deficiency and dysfunction, directly resulting in T cell immune dysfunction [134].

3.2 Regulatory T cells (Treg)

The hypoxic and acidic tumor microenvironment not only reduces anti-tumor immunity by blunting effector T-cell responses but also drives immune escape by encouraging the enlistment and function of pro-tumor immune cells that suppress the immune system (e.g., Tregs) [135]. Involved in maintaining immune balance, shielding against autoimmune conditions, and preventing excessive inflammation, Tregs are a distinct type of CD4+ T cells [136]. However, increased Treg ratios have been identified in the tumor microenvironment across various tumor types and are associated with a poor prognosis (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [137], non-small cell lung cancer [138], ovarian cancer [139] and glioblastoma [140]).

Basal levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are significantly higher in Tregs than in other T-cell subsets [141], and increased production of ROS by Tregs may be harmful to effector T-cells [142]. In addition, lactate uptake by Tregs upregulates the expression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), which largely influences Treg-mediated immunosuppression and the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade therapy [143].

3.3 Macrophages

Macrophages are classified as M1-like inflammatory and M2-like regulatory types [144]. M1 macrophages eliminate cancer cells, whereas M2 macrophages promote the growth of cancer cells [145]. As macrophages grow and mature, their metabolism shifts to glycolysis and lactate production. Interestingly, high extracellular lactate levels polarize macrophages into immunosuppressive M2-like macrophages [146]. Moreover, lactate can drive M2 polarization by mediating the expression of HIF1-α, thus causing an impact on the development of macrophages that results in the M2-like characteristic [147]. The uptake of lactate by macrophages induces arginase 1 (ARG1), which converts M1 macrophages into M2 macrophages [148]. ARG1 hinders the initiation and reproduction of T cells [149]. Lactate can also drive signals from the GPR81 receptor on macrophages, promoting the production of immunosuppressive agents with M2-like characteristics [150].

3.4 B-cell

B cells are the second type of adaptive immune cells found in the tumor microenvironment [151]. In an acidic microenvironment due to the presence of a tumor, B cells exhibit tumor growth-promoting properties [152]. B cells produce or induce other cells to produce interleukin-10 to suppress T cells [153, 154]. PD-L1+ B cells act on natural immune cells to promote immune tolerance [155]. In addition, B cells directly drive cancer cell growth by producing proinflammatory cytokines [156].

4. Aerobic glycolysis as a therapeutic target in the treatment of gastrointestinal tumors

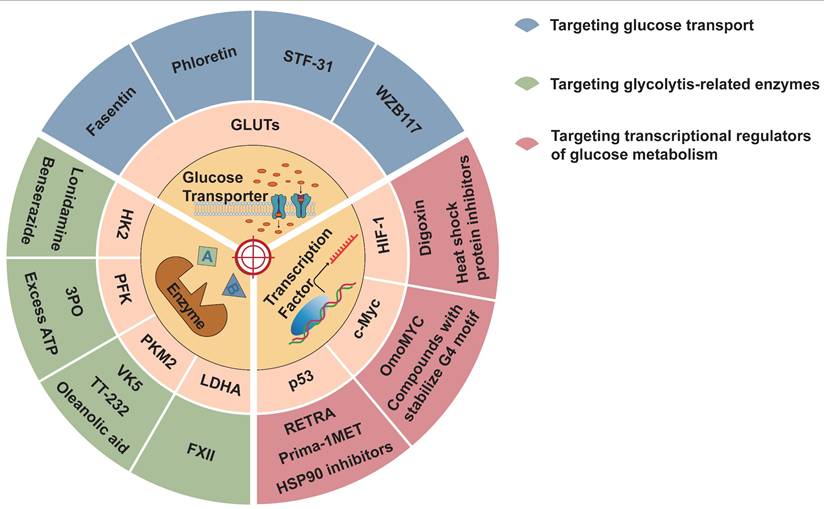

Aerobic glycolysis can promote tumor development, drug resistance, and suppression of antitumor immunity. Therefore, it is possible to interfere with different mechanisms of aerobic glycolysis to inhibit tumor occurrence and development. Several drugs and inhibitors targeting aerobic glycolysis are described below (Figure 4 and Table 2).

Inhibitors of aerobic glycolysis. Aerobic glycolysis inhibitors can be divided into three categories: those targeting the glucose transporter, glycolysis key enzymes, and transcription factors.

Glycolytic inhibitors that modulate glycolytic metabolism

| Target | Inhibitors | Mechanisms of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLUTs | Fasentin Phloretin STF-31 WZB117 | Inhibits glucose transport and reduces drug resistance Inhibits the expression of GLUTs and activates p53 Inhibits GLUT1 Inhibits GLUT1 and cell cycle; inhibits GLUT3 and EMT | [157] [158] [159] [160] |

| HK2 | Lonidamine 3-Bromopyruvate Benserazide | Inhibits HK2 Inhibits HK2 Inhibits HK2 | [163] [163] [163] |

| PFK | Excess ATP 3PO | Inhibits the activity of PFK Inhibits the activity of PFK | [164] [164] |

| PKM2 | TT-232 VK3 VK5 Compound 3 Oleanolic acid | Inhibits PKM2 Inhibits PKM2 Inhibits PKM2 Inhibits PKM2 Inhibits PKM2; converts PKM2 into PKM1 | [165] [165] [165] [165] [166] |

| LDHA | FXII | Inhibits LDHA; depletes intracellular ATP | [167] |

| HIF-1 | Digoxin Heat shock protein inhibitors | Inhibits HIF-1 expression Degrades HIF-1 | [168] [168] |

| C-Myc | OmoMYC BET protein inhibitor Compounds with stabilize G4 motif | Inhibits the binding of Myc-max to DNA and myc expression Reduce myc expression Reduce myc expression | [169] [170] [170] |

| p53 | Prima-1MET HSP90 inhibitors HDAC inhibitors RETRA PKC | Restores wild-type p53 function Induce degradation of mutant p53 Induce degradation of mutant p53 Disrupts the p53-p73 complex Inhibit the survival pathway of p53-mutated cells | [171] [172] [173] [174] [175] |

4.1 Targeting glucose transport

The transport of glucose into tumor cells via glucose transporters is the initial stage of glucose metabolism. Targeted glucose transporter therapy inhibits tumor occurrence and development. Drugs that target GLUT1 include fasentin, phloretin, STF-31, and WZB117. Fasentin can inhibit glucose transport and reduce resistance to caspase activation, thereby improving drug efficacy against tumors [157]. Phloretin inhibits the expression of GLUT1 and GLUT2 and activates p53 to suppress tumors by inhibiting the growth of colon cancer cells [158]. STF-31 selectively inhibits GLUT1, which hinders tumor growth and reduces tumor size with few side effects [159]. Similarly, WZB117 is a highly effective GLUT1 inhibitor that can irreversibly hinder the transport of glucose by GLUT1, thus inhibiting tumors from performing aerobic glycolysis and reducing the ATP concentration in cells, leading to cessation of the cell cycle [160]. Research findings indicate that targeting glycolysis can impede the proliferation of cancerous cells both in vivo and in vitro, and act synergistically with cisplatin and paclitaxel [161]. In addition, GLUT3 inhibition effectively inhibits EMT in colon cancer cells [162].

4.2 Targeting glycolytic-related enzymes

In most cases, glycolysis-related enzymes are overexpressed in tumors. Targeting these enzymes can effectively inhibit the Warburg effect, thereby controlling tumor growth and metastasis. Therapeutic modalities that target HK2 include HK2 inhibitors, such as Lonidamine, 3-Bromopyruvate, and benserazide, which have the potential to restrict the development, multiplication, and programmed cell death of cancerous cells [163].

Excess ATP and 3-(3-Pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one(3PO) [164] can inhibit the activity of PFK, thus hindering tumor growth. In addition, TT-232, VK3, VK5, and Compound 3 inhibit tumor cell glycolysis by inhibiting PKM2 [165]. Oleanolic acid can convert PKM2 into PKM1 to inhibit the function of PKM2 [166]. FXII, which inhibits LDHA, depletes intracellular ATP, leading to inhibition of tumor growth and cell death [167].

4.3 Targeting transcriptional regulators of glucose metabolism

Digoxin can inhibit HIF-1 expression as well as tumor growth and proliferation, and heat shock protein inhibitors can degrade HIF-1 [168]. OmoMYC can form homologous dimers that bind to DNA and inhibit c-Myc-max from binding to DNA and c-Myc expression [169]. Additionally, inhibitors of BET proteins and compounds that stabilize G4 motifs in the Myc promoter can reduce Myc expression and achieve tumor suppression [170]. Prima-1MET restores wild-type p53 function and inhibits tumor growth [171]. Studies have shown that HSP90 inhibitors [172] and HDAC inhibitors [173] can induce degradation of mutant p53 to achieve therapeutic effects in tumors. RETRA disrupts the p53-p73 complex and inhibits tumor growth via p53 mutations through a pathway that relies on p73 for its operation [174]. The inhibition of kinases involved in the G2/M checkpoint, such as PKC, can inhibit the survival pathway of p53-mutated cells and lead to the death of p53-mutated cells [175].

5. Conclusions and perspectives

A distinguishing feature of cancer is aerobic glycolysis, commonly referred to as the Warburg effect. Aerobic glycolysis is a common mechanism that supports the proliferation and metastasis of GI tumors. Glucose transporters (GLUT1, GLUT3, etc.), key enzymes (HK, PFK, PK), signaling pathways (PI3K/AKT, mTOR, AMPK, MAPK, and Wnt), and some transcription factors (HIF-1, c-Myc, and p53) are involved in the aerobic glycolysis of gastrointestinal tumors. The byproducts of aerobic glycolysis, including lactic acid, alter the tumor microenvironment, which affects the normal function of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, leading to weakened antitumor immunity and increased drug resistance. Therefore, aerobic glycolysis is a potential therapeutic target.

This paper reviews the roles of key enzymes in glycolysis, the regulation of related signaling pathways and transcription factors, and the alterations and roles of immune cells within the tumor milieu. These factors are key to the occurrence of metabolic rearrangement, apoptosis, the cell cycle, and drug resistance, thus largely affecting the growth, invasion, and metastasis of gastrointestinal tumors. Thus, aerobic glycolysis is a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of gastrointestinal tumors.

Abbreviations

AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; ATP: Adenosine triphosphate; 18F-FDG PET: 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; GLUT: Glucose transporter; HIF-1: Hypoxia-inducible factor; DHA: Dehydroascorbic acid; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; HK: Hexokinase; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; HKDC1: HK domain-containing 1; mTOR: Mechanistic target of rapamycin; PFKFB3: 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2:6-Biphosphatase; 3 PFK: Phosphofructokinase; PK: Pyruvate kinase; Treg: Regulatory T cells; PRAS40: Proline rich AKT substrate 40 kDa; MCT1: Monocarboxylate transporter 1; ENO1: Enolase 1; PDK1: Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1; INSR: Insulin receptor promoter; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81903000), Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2023NSFSC1846), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2022YFS0636-C4), Hejiang County People's Hospital-Southwest Medical University Science and Technology Cooperation Project (2022HJXNYD11, 2022HJXNYD16), and Luzhou Science and Technology Project (2021-jyj-81).

Author contributions

YLL and LP conceived and wrote the manuscript, and ZDQ and JL contributed to drawing the figures and designing the tables. YNL, ZJF, JMW, SL, SKH, HRZ, and collected data. LX and YHL provided guidance on the revision of this manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. WARBURG O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science (New York, NY). 1956;123:309-14

2. Guo W, Qiu Z, Wang Z, Wang Q, Tan N, Chen T. et al. MiR-199a-5p is negatively associated with malignancies and regulates glycolysis and lactate production by targeting hexokinase 2 in liver cancer. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2015;62:1132-44

3. Michelangelo C, Chin-Hsien T, Valentina P, Ping-Chih H, Claudio M. Lactate modulation of immune responses in inflammatory versus tumour microenvironments. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020 21

4. Kelloff G, Hoffman J, Johnson B, Scher H, Siegel B, Cheng E. et al. Progress and promise of FDG-PET imaging for cancer patient management and oncologic drug development. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:2785-808

5. Ziliang W, Wei C, Ling Z, Midie X, Yong W, Jiami H. et al. The Fibrillin-1/VEGFR2/STAT2 signaling axis promotes chemoresistance via modulating glycolysis and angiogenesis in ovarian cancer organoids and cells. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2022 42

6. Jun L, Qian Z, Yupeng G, Dingzhun L, Donggen J, Haiyun X. et al. Circular RNA circVAMP3 promotes aerobic glycolysis and proliferation by regulating LDHA in renal cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2022 13

7. Yan Z, Qiu P, Jinhua Z, Yuzhong Y, Xuemei Z, Aiyu M. et al. The function and mechanism of lactate and lactylation in tumor metabolism and microenvironment. Genes Dis. 2023 10

8. Runze S, Miao W, Bin D, Jianbing D, Jianlin W, Zekun L. et al. Long noncoding RNA SLC2A1-AS1 regulates aerobic glycolysis and progression in hepatocellular carcinoma via inhibiting the STAT3/FOXM1/GLUT1 pathway. Mol Oncol. 2020 14

9. Jie T, Jingpu Z, Yun L, Charles E M, Tie Fu L. Mitochondrial Sirtuin 4 Resolves Immune Tolerance in Monocytes by Rebalancing Glycolysis and Glucose Oxidation Homeostasis. Front Immunol. 2018 9

10. Vikas S S, Joanne M B. The Sweet Science of Glucose Transport. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023 33

11. Hongping X, Jianxiang C, Hengjun G, Shik Nie K, Amudha D, Ming S. et al. Hypoxia-induced modulation of glucose transporter expression impacts (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT imaging in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019 47

12. Hye Jin Y, Min L, Dong G, So Mi J, Su Hwan P, Je Sun L. et al. AMPK-HIF-1α signaling enhances glucose-derived de novo serine biosynthesis to promote glioblastoma growth. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023 42

13. Madan E, Gogna R, Bhatt M, Pati U, Kuppusamy P, Mahdi A. Regulation of glucose metabolism by p53: emerging new roles for the tumor suppressor. Oncotarget. 2011;2:948-57

14. Uldry M, Ibberson M, Hosokawa M, Thorens B. GLUT2 is a high affinity glucosamine transporter. FEBS letters. 2002;524:199-203

15. Cai K, Chen S, Zhu C, Li L, Yu C, He Z. et al. FOXD1 facilitates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis by regulating GLUT1-mediated aerobic glycolysis. Cell death & disease. 2022;13:765

16. Dai W, Xu Y, Mo S, Li Q, Yu J, Wang R. et al. GLUT3 induced by AMPK/CREB1 axis is key for withstanding energy stress and augments the efficacy of current colorectal cancer therapies. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2020;5:177

17. Liu J, Wen D, Fang X, Wang X, Liu T, Zhu J. p38MAPK Signaling Enhances Glycolysis Through the Up-Regulation of the Glucose Transporter GLUT-4 in Gastric Cancer Cells. Cellular physiology and biochemistry: international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2015;36:155-65

18. Park G, Jeong J, Kim D. GLUT5 regulation by AKT1/3-miR-125b-5p downregulation induces migratory activity and drug resistance in TLR-modified colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:1329-40

19. Sharen G, Peng Y, Cheng H, Liu Y, Shi Y, Zhao J. Prognostic value of GLUT-1 expression in pancreatic cancer: results from 538 patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:19760-7

20. Birte A, Guido M, Jasmin W, Kathy A, Angelika E, Stefan K. et al. Inhibiting PHGDH with NCT-503 reroutes glucose-derived carbons into the TCA cycle, independently of its on-target effect. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2021 36

21. Xiu-Lin F, Robertson A, Huan Y, Qiu-Yun C. The NIR inspired nano-CuSMn(II) composites for lactate and glycolysis attenuation. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019 181

22. Peng X, He Z, Yuan D, Liu Z, Rong P. Lactic acid: The culprit behind the immunosuppressive microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochimica et biophysica acta Reviews on cancer. 2024;1879:189164

23. Jin Q, Zi-Chen G, Yi-Na Z, Hong-Hua W, Jing Z, Li-Ting W. et al. Lactic acid promotes metastatic niche formation in bone metastasis of colorectal cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 2021 19

24. Yongwen L, Zhonghua Y, Ying Y, Peng Z. HIF1α lactylation enhances KIAA1199 transcription to promote angiogenesis and vasculogenic mimicry in prostate cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022 222

25. Fumimasa K, Takashi S, Noriko Y-Y, Kosuke Y, Akiho N, Juntaro Y. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts reuse cancer-derived lactate to maintain a fibrotic and immunosuppressive microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. JCI Insight. 2023 8

26. Roland C, Arumugam T, Deng D, Liu S, Philip B, Gomez S. et al. Cell surface lactate receptor GPR81 is crucial for cancer cell survival. Cancer research. 2014;74:5301-10

27. Xing W, Feng L, Zhigui L, Liming Z. ASIC3-activated key enzymes of de novo lipid synthesis supports lactate-driven EMT and the metastasis of colorectal cancer cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2024 22

28. Dhup S, Dadhich R, Porporato P, Sonveaux P. Multiple biological activities of lactic acid in cancer: influences on tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. Current pharmaceutical design. 2012;18:1319-30

29. Jin S, Xinyuan M, Lingzhi W, Zhian C, Weisheng W, Cuiyin Z. et al. Lactate/GPR81 recruits regulatory T cells by modulating CX3CL1 to promote immune resistance in a highly glycolytic gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2024 13

30. Yihui S, Hoang V D, Edward R C, Zihong C, Caroline R B, Tianxia X. et al. Mitochondrial ATP generation is more proteome efficient than glycolysis. Nat Chem Biol. 2024 20

31. Cheng H, Haiyue X, Zehao L, Dandan L, Siqi Z, Fang F. et al. Juglone promotes antitumor activity against prostate cancer via suppressing glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation. Phytother Res. 2022 37

32. Wang S, Li X, Wu L, Guo P, Feng L, Li B. MicroRNA-202 suppresses glycolysis of pancreatic cancer by targeting hexokinase 2. Journal of Cancer. 2021;12:1144-53

33. Huang X, Liu M, Sun H, Wang F, Xie X, Chen X. et al. HK2 is a radiation resistant and independent negative prognostic factor for patients with locally advanced cervical squamous cell carcinoma. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2015;8:4054-63

34. Zhang Z, Huang S, Wang H, Wu J, Chen D, Peng B. et al. High expression of hexokinase domain containing 1 is associated with poor prognosis and aggressive phenotype in hepatocarcinoma. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2016;474:673-9

35. Chen B, Cai T, Huang C, Zang X, Sun L, Guo S. et al. G6PD-NF-κB-HGF Signal in Gastric Cancer-Associated Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promotes the Proliferation and Metastasis of Gastric Cancer Cells by Upregulating the Expression of HK2. Frontiers in oncology. 2021;11:648706

36. Kim S, Jang J, Koh J, Kwon D, Kim Y, Paeng J. et al. Programmed cell death ligand-1-mediated enhancement of hexokinase 2 expression is inversely related to T-cell effector gene expression in non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research: CR. 2019;38:462

37. Tan V, Miyamoto S. HK2/hexokinase-II integrates glycolysis and autophagy to confer cellular protection. Autophagy. 2015;11:963-4

38. Shaun B, Michael R, Jörg B, Anke E, Teresa R. Structures of S. pombe phosphofructokinase in the F6P-bound and ATP-bound states. J Struct Biol. 2007 159

39. Kimberley M, Paula G-M, Rosaura E-P, Sara G-O, Yuxin D, Sara S-R. et al. BRAF activation by metabolic stress promotes glycolysis sensitizing NRAS(Q61)-mutated melanomas to targeted therapy. Nat Commun. 2022 13

40. Jong-Ho L, Rui L, Jing L, Yugang W, Lin T, Xin-Jian L. et al. EGFR-Phosphorylated Platelet Isoform of Phosphofructokinase 1 Promotes PI3K Activation. Mol Cell. 2018 70

41. Kim S, Manes N, El-Maghrabi M, Lee Y. Crystal structure of the hypoxia-inducible form of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFKFB3): a possible new target for cancer therapy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:2939-44

42. Lei L, Hong L, Ling Z, Zhong Y, Hu X, Li P. et al. A Potential Oncogenic Role for PFKFB3 Overexpression in Gastric Cancer Progression. Clinical and translational gastroenterology. 2021;12:e00377

43. Han J, Meng Q, Xi Q, Zhang Y, Zhuang Q, Han Y. et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates aerobic glycolysis by regulating PFKFB3 at early stage of colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2016;48:215-24

44. Bobarykina A, Minchenko D, Opentanova I, Moenner M, Caro J, Esumi H. et al. Hypoxic regulation of PFKFB-3 and PFKFB-4 gene expression in gastric and pancreatic cancer cell lines and expression of PFKFB genes in gastric cancers. Acta biochimica Polonica. 2006;53:789-99

45. Lin Y, Lv F, Liu F, Guo X, Fan Y, Gu F. et al. High Expression of Pyruvate Kinase M2 is Associated with Chemosensitivity to Epirubicin and 5-Fluorouracil in Breast Cancer. Journal of Cancer. 2015;6:1130-9

46. Hanahan D, Weinberg R. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-74

47. Irey E, Lassiter C, Brady N, Chuntova P, Wang Y, Knutson T. et al. JAK/STAT inhibition in macrophages promotes therapeutic resistance by inducing expression of protumorigenic factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2019;116:12442-51

48. Yu Z, Wang D, Tang Y. PKM2 promotes cell metastasis and inhibits autophagy via the JAK/STAT3 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2021;476:2001-10

49. Azoitei N, Becher A, Steinestel K, Rouhi A, Diepold K, Genze F. et al. PKM2 promotes tumor angiogenesis by regulating HIF-1α through NF-κB activation. Molecular cancer. 2016;15:3

50. Gao S, Chen M, Wei W, Zhang X, Zhang M, Yao Y. et al. Crosstalk of mTOR/PKM2 and STAT3/c-Myc signaling pathways regulate the energy metabolism and acidic microenvironment of gastric cancer. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2018

51. Wang W, Liu Z, Chen X, Lu Y, Wang B, Li F. et al. FABP5Downregulation of Suppresses the Proliferation and Induces the Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer Cells Through the Hippo Signaling Pathway. DNA and cell biology. 2021;40:1076-86

52. Shen X, Zhao J, Wang Q, Chen P, Hong Y, He X. et al. The Invasive Potential of Hepatoma Cells Induced by Radiotherapy is Related to the Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells and Could be Inhibited by EGCG Through the TLR4 Signaling Pathway. Radiation research. 2022;197:365-75

53. Xiu D, Liu G, Yu S, Li L, Zhao G, Liu L. et al. Long non-coding RNA LINC00968 attenuates drug resistance of breast cancer cells through inhibiting the Wnt2/β-catenin signaling pathway by regulating WNT2. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research: CR. 2019;38:94

54. Bao S, Ji Z, Shi M, Liu X. EPB41L5 promotes EMT through the ERK/p38 MAPK signaling pathway in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Pathology, research and practice. 2021;228:153682

55. Voss C, Andersen J, Jakobsen E, Siamka O, Karaca M, Maechler P. et al. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulates astrocyte oxidative metabolism by balancing TCA cycle dynamics. Glia. 2020;68:1824-39

56. Okrah E, Wang Q, Fu H, Chen Q, Gao J. PdpaMn inhibits fatty acid synthase-mediated glycolysis by down-regulating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in breast cancer. Anti-cancer drugs. 2020;31:1046-56

57. Shin N, Lee HJ, Sim DY, Im E, Park JE, Park WY. et al. Apoptotic effect of compound K in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via inhibition of glycolysis and Akt/mTOR/c-Myc signaling. Phytother Res. 2021;35:3812-20

58. He H, Chen T, Mo H, Chen S, Liu Q, Guo C. Hypoxia-inducible long noncoding RNA NPSR1-AS1 promotes the proliferation and glycolysis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by regulating the MAPK/ERK pathway. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2020;533:886-92

59. Fan Q, Yang L, Zhang X, Ma Y, Li Y, Dong L. et al. Autophagy promotes metastasis and glycolysis by upregulating MCT1 expression and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research: CR. 2018;37:9

60. Ciccarese F, Zulato E, Indraccolo S. LKB1/AMPK Pathway and Drug Response in Cancer: A Therapeutic Perspective. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:8730816

61. Ren Y, Chen J, Chen P, Hao Q, Cheong L, Tang M. et al. Oxidative stress-mediated AMPK inactivation determines the high susceptibility of LKB1-mutant NSCLC cells to glucose starvation. Free radical biology & medicine. 2021;166:128-39

62. Xu X, Ding G, Liu C, Ding Y, Chen X, Huang X. et al. Nuclear UHRF1 is a gate-keeper of cellular AMPK activity and function. Cell research. 2022;32:54-71

63. de Wendt C, Espelage L, Eickelschulte S, Springer C, Toska L, Scheel A. et al. Contraction-Mediated Glucose Transport in Skeletal Muscle Is Regulated by a Framework of AMPK, TBC1D1/4, and Rac1. Diabetes. 2021;70:2796-809

64. Wang Y, Luo M, Wang F, Tong Y, Li L, Shu Y. et al. AMPK induces degradation of the transcriptional repressor PROX1 impairing branched amino acid metabolism and tumourigenesis. Nature communications. 2022;13:7215

65. Inoki K, Ouyang H, Zhu T, Lindvall C, Wang Y, Zhang X. et al. TSC2 integrates Wnt and energy signals via a coordinated phosphorylation by AMPK and GSK3 to regulate cell growth. Cell. 2006;126:955-68

66. Gwinn D, Shackelford D, Egan D, Mihaylova M, Mery A, Vasquez D. et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Molecular cell. 2008;30:214-26

67. Hsu C, Peng D, Cai Z, Lin H. AMPK signaling and its targeting in cancer progression and treatment. Seminars in cancer biology. 2022;85:52-68

68. Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan K. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:132-41

69. Mo J, Meng Z, Kim Y, Park H, Hansen C, Kim S. et al. Cellular energy stress induces AMPK-mediated regulation of YAP and the Hippo pathway. Nature cell biology. 2015;17:500-10

70. Li Y, Luo J, Mosley Y, Hedrick V, Paul L, Chang J. et al. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Directly Phosphorylates and Destabilizes Hedgehog Pathway Transcription Factor GLI1 in Medulloblastoma. Cell reports. 2015;12:599-609

71. Zheng C, Yu X, Liang Y, Zhu Y, He Y, Liao L. et al. Targeting PFKL with penfluridol inhibits glycolysis and suppresses esophageal cancer tumorigenesis in an AMPK/FOXO3a/BIM-dependent manner. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2022;12:1271-87

72. Liu W, Liu X, Liu Y, Ling T, Chen D, Otkur W. et al. PLIN2 promotes HCC cells proliferation by inhibiting the degradation of HIF1α. Experimental cell research. 2022: 113244.

73. Guerrero-Zotano A, Mayer I, Arteaga C. PI3K/AKT/mTOR: role in breast cancer progression, drug resistance, and treatment. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2016;35:515-24

74. Sarker K, Lee K. L6 myoblast differentiation is modulated by Cdk5 via the PI3K-AKT-p70S6K signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23:6064-70

75. Novellasdemunt L, Tato I, Navarro-Sabate A, Ruiz-Meana M, Méndez-Lucas A, Perales J. et al. Akt-dependent activation of the heart 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFKFB2) isoenzyme by amino acids. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:10640-51

76. Li C, Chen Q, Zhou Y, Niu Y, Wang X, Li X. et al. S100A2 promotes glycolysis and proliferation via GLUT1 regulation in colorectal cancer. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2020;34:13333-44

77. Samih N, Hovsepian S, Aouani A, Lombardo D, Fayet G. Glut-1 translocation in FRTL-5 thyroid cells: role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and N-glycosylation. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4146-55

78. Huang F, Chen J, Wang J, Zhu P, Lin W. Palmitic Acid Induces MicroRNA-221 Expression to Decrease Glucose Uptake in HepG2 Cells via the PI3K/AKT/GLUT4 Pathway. BioMed research international. 2019;2019:8171989

79. Riaz F, Chen Q, Lu K, Osoro E, Wu L, Feng L. et al. Inhibition of miR-188-5p alleviates hepatic fibrosis by significantly reducing the activation and proliferation of HSCs through PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2021;25:4073-87

80. Pan R, Zhao Z, Xu D, Li C, Xia Q. GPX4 transcriptionally promotes liver cancer metastasis via GRHL3/PTEN/PI3K/AKT axis. Translational research: the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2024;271:79-92

81. Ji H, Ma J, Chen L, Chen T, Zhang S, Jia J. et al. Pyrroloquinoline Quinine and LY294002 Changed Cell Cycle and Apoptosis by Regulating PI3K-AKT-GSK3β Pathway in SH-SY5Y Cells. Neurotoxicity research. 2020;38:266-73

82. Cho D, Choi Y, Jo S, Ryou J, Kim J, Chung J. et al. Troglitazone acutely inhibits protein synthesis in endothelial cells via a novel mechanism involving protein phosphatase 2A-dependent p70 S6 kinase inhibition. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2006;291:C317-26

83. Ziegler M, Hatch M, Wu N, Muawad S, Hughes C. mTORC2 mediates CXCL12-induced angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2016;19:359-71

84. Zhao C, Tao T, Yang L, Qin Q, Wang Y, Liu H. et al. Loss of PDZK1 expression activates PI3K/AKT signaling via PTEN phosphorylation in gastric cancer. Cancer letters. 2019;453:107-21

85. Shen X, Si Y, Wang Z, Wang J, Guo Y, Zhang X. Quercetin inhibits the growth of human gastric cancer stem cells by inducing mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis through the inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling. International journal of molecular medicine. 2016;38:619-26

86. Coleman N, Subbiah V, Pant S, Patel K, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Yedururi S. et al. Emergence of mTOR mutation as an acquired resistance mechanism to AKT inhibition, and subsequent response to mTORC1/2 inhibition. NPJ precision oncology. 2021;5:99

87. Kim D, Sarbassov D, Ali S, Latek R, Guntur K, Erdjument-Bromage H. et al. GbetaL, a positive regulator of the rapamycin-sensitive pathway required for the nutrient-sensitive interaction between raptor and mTOR. Molecular cell. 2003;11:895-904

88. Liu X, Yamaguchi K, Takane K, Zhu C, Hirata M, Hikiba Y. et al. Cancer-associated IDH mutations induce Glut1 expression and glucose metabolic disorders through a PI3K/Akt/mTORC1-Hif1α axis. PloS one. 2021;16:e0257090

89. Düvel K, Yecies J, Menon S, Raman P, Lipovsky A, Souza A. et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Molecular cell. 2010;39:171-83

90. Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, Lin S, Rüegg M, Hall A. et al. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nature cell biology. 2004;6:1122-8

91. Zhang H, Su X, Burley S, Zheng X. mTOR regulates aerobic glycolysis through NEAT1 and nuclear paraspeckle-mediated mechanism in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 2022;12:3518-33

92. Wang G, Yu Y, Wang YZ, Yin PH, Xu K, Zhang H. The effects and mechanisms of isoliquiritigenin loaded nanoliposomes regulated AMPK/mTOR mediated glycolysis in colorectal cancer. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2020;48:1231-49

93. Csibi A, Lee G, Yoon S, Tong H, Ilter D, Elia I. et al. The mTORC1/S6K1 pathway regulates glutamine metabolism through the eIF4B-dependent control of c-Myc translation. Current biology: CB. 2014;24:2274-80

94. Xiaoyu H, Yiru Y, Shuisheng S, Keyan C, Zixing Y, Shanglin C. et al. The mTOR Pathway Regulates PKM2 to Affect Glycolysis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018;17:1533033818780063

95. Cargnello M, Roux P. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 2011;75:50-83

96. Ni R, Cao T, Ji X, Peng A, Zhang Z, Fan G. et al. DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 positively regulates RIPK1-mediated necroptosis. Cell death and differentiation. 2024

97. Novellasdemunt L, Bultot L, Manzano A, Ventura F, Rosa J, Vertommen D. et al. PFKFB3 activation in cancer cells by the p38/MK2 pathway in response to stress stimuli. The Biochemical journal. 2013;452:531-43

98. Bertero T, Oldham W, Cottrill K, Pisano S, Vanderpool R, Yu Q. et al. Vascular stiffness mechanoactivates YAP/TAZ-dependent glutaminolysis to drive pulmonary hypertension. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2016;126:3313-35

99. Liu Q, Luo Q, Deng B, Ju Y, Song G. Stiffer Matrix Accelerates Migration of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells through Enhanced Aerobic Glycolysis Via the MAPK-YAP Signaling. Cancers. 2020 12

100. Lee S, Jeon H, Ju M, Kim C, Yoon G, Han S. et al. Wnt/Snail signaling regulates cytochrome C oxidase and glucose metabolism. Cancer research. 2012;72:3607-17

101. Yang L, Perez A, Fujie S, Warden C, Li J, Wang Y. et al. Wnt modulates MCL1 to control cell survival in triple negative breast cancer. BMC cancer. 2014;14:124

102. Perciavalle R, Stewart D, Koss B, Lynch J, Milasta S, Bathina M. et al. Anti-apoptotic MCL-1 localizes to the mitochondrial matrix and couples mitochondrial fusion to respiration. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:575-83

103. Li Z, Yang Z, Liu W, Zhu W, Yin L, Han Z. et al. Disheveled3 enhanced EMT and cancer stem-like cells properties via Wnt/β-catenin/c-Myc/SOX2 pathway in colorectal cancer. Journal of translational medicine. 2023;21:302

104. Nie X, Wang H, Wei X, Li L, Xue T, Fan L. et al. LRP5 Promotes Gastric Cancer via Activating Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin and Glycolysis Pathways. The American journal of pathology. 2022;192:503-17

105. Lunt S, Vander Heiden M. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2011;27:441-64

106. Macheda ML, Rogers S, Best JD. Molecular and cellular regulation of glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:654-62

107. Guadall A, Orriols M, Rodríguez-Calvo R, Calvayrac O, Crespo J, Aledo R. et al. Fibulin-5 is up-regulated by hypoxia in endothelial cells through a hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1α)-dependent mechanism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:7093-103

108. Lu H, Forbes R, Verma A. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation by aerobic glycolysis implicates the Warburg effect in carcinogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:23111-5

109. Macheda M, Rogers S, Best J. Molecular and cellular regulation of glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins in cancer. Journal of cellular physiology. 2005;202:654-62

110. Ziyan Z, Jingqi Y, Saeid T, Ke Jian L, Honglian S. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 contributes to N-acetylcysteine's protection in stroke. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013 68

111. Kim J, Gao P, Liu Y, Semenza G, Dang C. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and dysregulated c-Myc cooperatively induce vascular endothelial growth factor and metabolic switches hexokinase 2 and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:7381-93

112. Hao Z, Xiangyu Z, Yanfeng L, Zhijia X, Tong X, Gang D. et al. NOP2-mediated m5C Modification of c-Myc in an EIF3A-Dependent Manner to Reprogram Glucose Metabolism and Promote Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression. Research (Wash D C). 2023 6

113. He T, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Li X, Zhu H, Zheng K. The c-Myc-LDHA axis positively regulates aerobic glycolysis and promotes tumor progression in pancreatic cancer. Medical oncology (Northwood, London, England). 2015;32:187

114. Wang S, Wang Y, Li S, Nian S, Xu W, Liang F. Far upstream element -binding protein 1 (FUBP1) participates in the malignant process and glycolysis of colon cancer cells by combining with c-Myc. Bioengineered. 2022;13:12115-26

115. Wang P, Jin J, Liang X, Yu M, Yang C, Huang F. et al. Helichrysetin inhibits gastric cancer growth by targeting c-Myc/PDHK1 axis-mediated energy metabolism reprogramming. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2022;43:1581-93

116. Zawacka-Pankau J, Grinkevich V, Hünten S, Nikulenkov F, Gluch A, Li H. et al. Inhibition of glycolytic enzymes mediated by pharmacologically activated p53: targeting Warburg effect to fight cancer. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:41600-15

117. Gatenby R, Gawlinski E. The glycolytic phenotype in carcinogenesis and tumor invasion: insights through mathematical models. Cancer research. 2003;63:3847-54

118. Hsu P, Sabatini D. Cancer cell metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell. 2008;134:703-7

119. Na-Jin G, Ming-Zhe W, Ling H, Xu-Bo W, Shiyu W, Xue-Shan Q. et al. HPV 16 E6/E7 up-regulate the expression of both HIF-1α and GLUT1 by inhibition of RRAD and activation of NF-κB in lung cancer cells. J Cancer. 2019 10

120. Bieging K, Mello S, Attardi L. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nature reviews Cancer. 2014;14:359-70

121. Liu K, Li F, Han H, Chen Y, Mao Z, Luo J. et al. Parkin Regulates the Activity of Pyruvate Kinase M2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2016;291:10307-17

122. Ravi K, Hung-Ju S, Meng-Hsun W, ChikOn C, Tai-Du L, Linyi C. et al. The antagonism between MCT-1 and p53 affects the tumorigenic outcomes. Mol Cancer. 2010 9

123. Contractor T, Harris C. p53 negatively regulates transcription of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase Pdk2. Cancer research. 2012;72:560-7

124. Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak M, Vidal M, Nakano K, Bartrons R. et al. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:107-20

125. Mathupala S, Rempel A, Pedersen P. Glucose catabolism in cancer cells: identification and characterization of a marked activation response of the type II hexokinase gene to hypoxic conditions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:43407-12

126. Matoba S, Kang J, Patino W, Wragg A, Boehm M, Gavrilova O. et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science (New York, NY). 2006;312:1650-3

127. Liu M, Hu Y, Lu S, Lu M, Li J, Chang H. et al. IC261, a specific inhibitor of CK1δ/ε, promotes aerobic glycolysis through p53-dependent mechanisms in colon cancer. International journal of biological sciences. 2020;16:882-92

128. Butera G, Pacchiana R, Mullappilly N, Margiotta M, Bruno S, Conti P. et al. Mutant p53 prevents GAPDH nuclear translocation in pancreatic cancer cells favoring glycolysis and 2-deoxyglucose sensitivity. Biochimica et biophysica acta Molecular cell research. 2018;1865:1914-23

129. Mondal P, Gadad S, Adhikari S, Ramos E, Sen S, Prasad P. et al. TCF19 and p53 regulate transcription of TIGAR and SCO2 in HCC for mitochondrial energy metabolism and stress adaptation. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2021;35:e21814

130. Sukumar M, Liu J, Ji Y, Subramanian M, Crompton J, Yu Z. et al. Inhibiting glycolytic metabolism enhances CD8+ T cell memory and antitumor function. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:4479-88

131. Frauwirth K, Riley J, Harris M, Parry R, Rathmell J, Plas D. et al. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity. 2002;16:769-77

132. Fischer K, Hoffmann P, Voelkl S, Meidenbauer N, Ammer J, Edinger M. et al. Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid on human T cells. Blood. 2007;109:3812-9

133. Haas R, Smith J, Rocher-Ros V, Nadkarni S, Montero-Melendez T, D'Acquisto F. et al. Lactate Regulates Metabolic and Pro-inflammatory Circuits in Control of T Cell Migration and Effector Functions. PLoS biology. 2015;13:e1002202

134. Zhang Y, Kurupati R, Liu L, Zhou X, Zhang G, Hudaihed A. et al. Enhancing CD8 T Cell Fatty Acid Catabolism within a Metabolically Challenging Tumor Microenvironment Increases the Efficacy of Melanoma Immunotherapy. Cancer cell. 2017;32:377-91.e9

135. Jinren Z, Jian G, Qufei Q, Yigang Z, Tianning H, Xiangyu L. et al. Lactate supports Treg function and immune balance via MGAT1 effects on N-glycosylation in the mitochondria. J Clin Invest. 2024 134

136. Giang T T, Suzanne J H, Nicole M C, Nirupama D V, Karren M P, Rochelle B. et al. IL-5 promotes induction of antigen-specific CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells that suppress autoimmunity. Blood. 2012 119

137. Yaqing Z, Jenny L, Nina G S, Wei Y, Ho-Joon L, Zeribe C N. et al. Regulatory T-cell Depletion Alters the Tumor Microenvironment and Accelerates Pancreatic Carcinogenesis. Cancer Discov. 2020 10

138. Tao H, Mimura Y, Aoe K, Kobayashi S, Yamamoto H, Matsuda E. et al. Prognostic potential of FOXP3 expression in non-small cell lung cancer cells combined with tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2012;75:95-101

139. Leffers N, Gooden M, de Jong R, Hoogeboom B, ten Hoor K, Hollema H. et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes in primary and metastatic lesions of advanced stage ovarian cancer. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII. 2009;58:449-59

140. Sayour E, McLendon P, McLendon R, De Leon G, Reynolds R, Kresak J. et al. Increased proportion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with tumor recurrence and reduced survival in patients with glioblastoma. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII. 2015;64:419-27

141. Beier U, Angelin A, Akimova T, Wang L, Liu Y, Xiao H. et al. Essential role of mitochondrial energy metabolism in Foxp3⁺ T-regulatory cell function and allograft survival. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2015;29:2315-26

142. Fu G, Xu Q, Qiu Y, Jin X, Xu T, Dong S. et al. Suppression of Th17 cell differentiation by misshapen/NIK-related kinase MINK1. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2017;214:1453-69

143. Kumagai S, Koyama S, Itahashi K, Tanegashima T, Lin Y, Togashi Y. et al. Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer cell. 2022;40:201-18.e9

144. Baolong L, Phuong Linh N, Han Y, Xingzhi L, Huiren W, Jeffrey P. et al. Critical contributions of protein cargos to the functions of macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023 21

145. Sri Murugan Poongkavithai V, Yeoul K, Gowri Rangaswamy G, Seok-Min L, Min-Sung P, Dong Gyun J. et al. IL4 receptor targeting enables nab-paclitaxel to enhance reprogramming of M2-type macrophages into M1-like phenotype via ROS-HMGB1-TLR4 axis and inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis. Theranostics. 2024 14

146. Colegio O, Chu N, Szabo A, Chu T, Rhebergen A, Jairam V. et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 2014;513:559-63

147. Stone S, Rossetti R, Alvarez K, Carvalho J, Margarido P, Baracat E. et al. Lactate secreted by cervical cancer cells modulates macrophage phenotype. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2019;105:1041-54

148. Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C, Weng Y. et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature. 2019;574:575-80

149. Ohashi T, Akazawa T, Aoki M, Kuze B, Mizuta K, Ito Y. et al. Dichloroacetate improves immune dysfunction caused by tumor-secreted lactic acid and increases antitumor immunoreactivity. International journal of cancer. 2013;133:1107-18

150. Hoque R, Farooq A, Ghani A, Gorelick F, Mehal W. Lactate reduces liver and pancreatic injury in Toll-like receptor- and inflammasome-mediated inflammation via GPR81-mediated suppression of innate immunity. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1763-74

151. Tokunaga R, Naseem M, Lo J, Battaglin F, Soni S, Puccini A. et al. B cell and B cell-related pathways for novel cancer treatments. Cancer treatment reviews. 2019;73:10-9

152. Limei S, Jingjing L, Qi L, Manisit D, Wantong S, Xueqiong Z. et al. Nano-trapping CXCL13 reduces regulatory B cells in tumor microenvironment and inhibits tumor growth. J Control Release. 2022 343

153. Glass M, Glass D, Oliveria J, Mbiribindi B, Esquivel C, Krams S. et al. Human IL-10-producing B cells have diverse states that are induced from multiple B cell subsets. Cell reports. 2022;39:110728

154. Zhang B, Vogelzang A, Miyajima M, Sugiura Y, Wu Y, Chamoto K. et al. B cell-derived GABA elicits IL-10 macrophages to limit anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2021;599:471-6

155. Li X, Du H, Zhan S, Liu W, Wang Z, Lan J. et al. The interaction between the soluble programmed death ligand-1 (sPD-L1) and PD-1 regulator B cells mediates immunosuppression in triple-negative breast cancer. Frontiers in immunology. 2022;13:830606