Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2026; 17(2):290-299. doi:10.7150/jca.122078 This issue Cite

Review

Sialylation in Thyroid Carcinoma: An Overview of Mechanisms, Markers, and Therapeutic Opportunities

Department of General Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, No. 300 Guangzhou Road, Nanjing, 210029, China.

#These authors contribute equally to the work.

Received 2025-7-20; Accepted 2025-12-17; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Thyroid carcinoma (TC) is the most prevalent malignancy of the endocrine system, with its incidence rising annually worldwide. Post-translational modifications and epigenetic changes have been documented to be pivotal in the initiation, progression, and malignant transformation of TC. In addition to mediating biological processes such as cell recognition, signal transduction, and immune regulation, these modifications can also significantly impact the development and metastasis of various cancers. Among these, sialylation is identified as a key post-translational modification, showing close associations with the invasiveness and metastatic potential of TC. This review aims to provide an overview of the current understanding of sialylation in TC, highlighting its underlying mechanisms and examining its roles in cell proliferation, invasion, and immune evasion. Additionally, this study intends to explore the potential of targeting sialylation as a novel therapeutic approach, providing new perspectives for TC prevention and treatment, as well as the development of new therapeutic agents.

Keywords: thyroid carcinoma, sialylation, sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins

1. Introduction

Thyroid carcinoma (TC) is the most prevalent malignancy of the endocrine system, ranking as the seventh most common cancer worldwide given its newly diagnosed cases of over 821,000 in 2022[1]. Its development and progression may be attributed to various risk factors, such as chromosomal and genetic mutations, iodine intake, radiation history, autoimmune thyroid diseases, gender, estrogen, obesity, lifestyle changes, and environmental pollutants, etc[2]. Based on tumor origin and differentiation status, TC is classified into several subtypes, including papillary TC (PTC), follicular TC (FTC), poorly differentiated TC (PDTC), anaplastic TC (ATC), and medullary TC (MTC), the latter of which originates from parafollicular C cells. Among these, PTC is the most common histotype, accounting for approximately 90% of all TCs. PTC and FTC are collectively referred to as differentiated TC (DTC)[3].

The occurrence and progression of TC involve complex molecular mechanisms and regulatory networks. Protein modifications serve as crucial regulatory mechanisms in various physiological and pathological processes intracellularly, which have been highly concerned in recent decades. These modifications include phosphorylation, glycosylation, ubiquitination, methylation, etc[4]. Beyond impacts on the structure, function, and stability of proteins, such modifications can also regulate intracellular signaling, immune response, and biological processes such as cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis[5,6]. Advancement in research within this field has highlighted the critical role of abnormal protein modifications in tumor initiation, progression, and the acquisition of malignant traits, offering new insights into the mechanisms underlying TC and potential therapeutic strategies. Among these modifications, glycosylation has gained increasing interest in oncology. It refers to a specific enzymatic process in which carbohydrate moieties are added to specific amino acid residues on proteins by glycosyltransferases, forming glycosidic bonds. It encompasses various modifications, such as sialylation, fucosylation, and O-glycan truncation[7]. Abnormal sialylation is one of the most common glycosylation progresses in cancer, and has become a major area of focus in tumor research[8-10]. Existing evidence indicates the important position sialylation occupied in the development of TC. Accordingly, this review aims to summarize the specific roles of sialylation in TC.

2. Sialic Acids and Sialylation

2.1 Biochemical Characteristics of Sialic Acids

Sialic acids are a class of acidic sugar molecules containing nine carbon atoms, with wide distribution on the surface of animal and plant cells, as well as on certain biomolecules. Typically, sialic acids locate at the ends of glycoproteins or glycolipids, where they serve as 'bridge' molecules that facilitate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions[11]. These compounds were first isolated by Gunnar Blix in 1936 from submandibular gland mucoproteins, named 'sialic acid'[12]. In the early 1940s, Ernst Klenk isolated acidic gangliosides composed of neurotransmitters, fatty acids, hexoses, and neuraminic acids abundant in the brain[13]. In 1957, Blix and colleagues found that neuraminic acids shared structural similarities with sialic acids[14]. Sialic acids exhibit distinctive structures, characterized by a carbon atom bearing both an amine and a carboxyl group, imparting strong acidity and hydrophilicity. The most common forms of sialic acids are N-Acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac or ManNAc) and its derivative, N-Glycolylneuraminic acid[15]. In malignant tumors, aberrant sialylation of cell surface glycans may alter charge properties and steric hindrance, thereby facilitating tumor cell dissociation, invasion, and metastasis directly[16,17].

2.2 Enzymatic Process of Sialylation

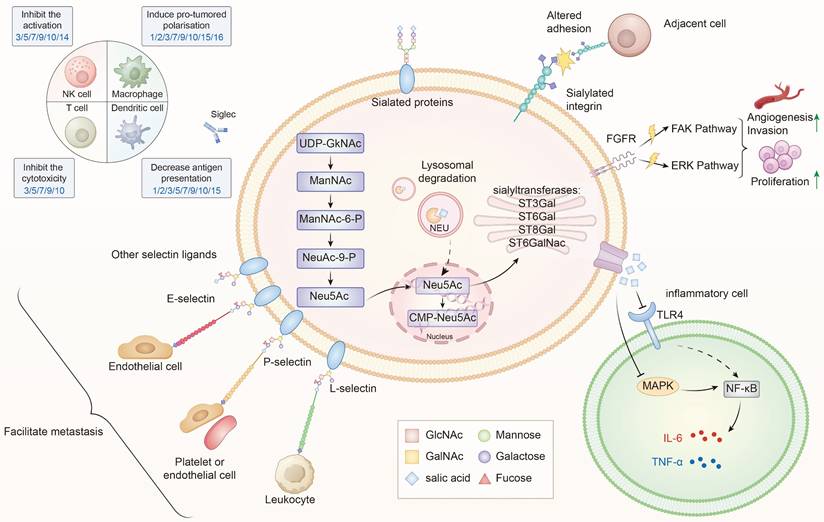

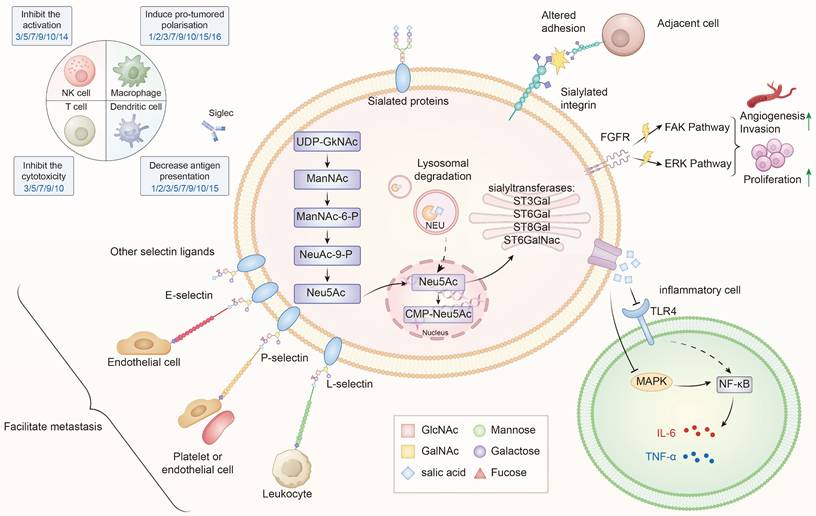

Sialylation, or the covalent addition of sialic acids to the terminal end of glycoproteins, is a biologically significant modification involved in processes such as embryonic development, neurodevelopment, reprogramming, tumorigenesis, and immune responses[9,18-20]. Over 50 subtypes of sialic acids have been identified, with Neu5Ac being the most prevalent form in humans[21]. Figure 1 provides an overview of the sialylation process.

3. Role of Sialylation in Tumorigenesis

In TC, abnormal sialylation has been directly implicated in tumor initiation and progression. Early studies demonstrated that elevated serum and tissue levels of total sialic acids (TSA) could serve as markers for TC[22]. More recent investigations revealed that dysregulated expression of sialyltransferases (STs), such as ST6GAL1 and ST6GAL2, was associated with lymph node metastasis, advanced clinical stage, and poor prognosis in TC patients[23,24]. These findings underscore the clinical relevance of sialylation in TC.

Beyond TC, evidence from other malignancies provides additional mechanistic insights. Abnormal sialylation, mainly regulated by STs and neuraminidases (NEUs), can disturb the balance of sialic acids and drive uncontrolled proliferation, invasion, migration, and immune suppression[25-27]. To date, existing research has identified 20 STs and 4 NEUs, which can mediate α-2,3, α-2,6, or α-2,8 linkages[28]. Table 1 summarizes the specific roles of related enzymes in TC, while Table 2 covers their roles in other malignancies over the past five years.

Besides STs and NEUs, other molecules are also engaged in tumor sialylation. The part related to TC will be elaborated below.

Roles of related enzymes in TC

| Thyroid carcinoma | Enzymes | Roles | Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTC | ST3GAL1 | promotion | Associates with dedifferentiation[85] |

| ST6GAL1 | promotion | Associates with lymph node metastasis, clinical staging, and decreased survival rates[23] | |

| ST8SIA4 | promotion | Increases metastatic potential[86] | |

| FTC | ST6GAL2 | promotion | Inactivates the Hippo signaling pathway[24] |

| ST6GALNAC2 | promotion | modulates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway[36] | |

| ST6GALNAC4 | promotion | modulates the invasion and tumorigenicity[37] |

4. Sialylation-Mediated Malignant Behaviors in TC

In the 1980s, Kokoglu et al. for the first time identified that TSA in serum and tissues could serve as markers for TC[22]. Later, in 2006, Pavel et al. demonstrated the significance of elevated sialic acid levels on the thyroid cell membrane as an important pathological indicator for distinguishing between benign and malignant thyroid lesions[29]. Other related molecular markers have also been identified to be essential in the onset and progression of PTC. Moreover, sialylation has been confirmed to be involved in the malignant progression of various subtypes of TC, including key biological behaviors such as tumor cell proliferation, dedifferentiation, migration, invasion, and immune escape. We will continue to explore the potential mechanisms of these effects (Figure 1).

4.1 Sialylation and Malignant Phenotypes in DTC

Tumor metastasis refers to the process by which primary tumor cells shed from the primary site and migrate to other parts of the body (e.g., nearby blood vessels or the lymphatic system, etc.) through a series of complex biological mechanisms. Beyond a defining characteristic of malignant tumors, tumor metastasis is also accepted as a major contributor to poor prognosis and mortality in cancer patients[30]. Through the alteration of their adhesion properties, sialylation of cells, the extracellular matrix, and adhesion molecules (e.g., integrins) occupy critical positions in enhancing the metastatic potential of various cancers[16,31].

The role of sialylation in thyroid cancer progression. Sialylation in TC is regulated by STs (ST3Gal, ST6Gal, ST8Gal ang ST6GalNAc) and NEUs, which dynamically control the addition or removal of sialic acids. Within the cell, sialic acids are synthesized from UDP-GlcNAc through the ManNAc-Neu5Ac pathway, subsequently activated to CMP-Neu5Ac in the nucleus and utilized in the Golgi apparatus for glycoprotein and glycolipid sialylation[83]. Aberrant sialylation leads to multiple oncogenic effects: (1) Altered adhesion and metastasis—sialylated integrins and selectin ligands (E-, P-, L-selectins) facilitate interactions with endothelial cells, leukocytes, and platelets, promoting tumor dissemination; (2) Activation of signaling pathways—sialylated FGFR and integrins activate FAK and ERK cascades, driving proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis; (3) Immune evasion—sialylated ligands engage Siglec receptors on NK cells, T cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, inhibiting cytotoxicity, dampening activation, and inducing pro-tumoral polarization; (4) Inflammatory modulation—via TLR4-MAPK-NF-κB signaling, sialylation influences cytokine secretion (IL-6, TNF-α) and shapes the tumor microenvironment. Collectively, these processes contribute to the malignant progression of TC by promoting proliferation, invasion, immune suppression, and metastatic spread[16,84].

4.1.1 Mechanisms in PTC

Abnormal regulation of sialylation can profoundly alter the glycan structures on the surface of tumor cells in PTC, thus facilitating the interactions with other cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME)[32]. It may further advance tumor invasion and metastasis. Low et al. discovered that in the diffuse sclerosing variant of PTC (DSVPTC), lymphoid aggregates could induce the formation of small venules resembling high endothelial venules (HEVs) found in secondary lymphoid organs. These venules further facilitated tumor cell-lymphatic endothelial cell interactions through the expression of 6-sulfo-sialyl Lewis X and intercellular adhesion molecule 1, thereby altering the TME and promoting lymph node metastasis in DSVPTC[33]. Zhang et al. identified a significant positive correlation between several N-glycan biomarkers and lymph node metastasis in PTC, offering potential biomarker of glycan modifications for classifying PTC patients into low- or high-risk groups for lymph node metastasis[34]. Additionally, compared to typical PTC, the follicular variant of PTC (FVPTC) had significantly higher mRNA levels of ST6GAL1, which exhibited strong correlations with lymph node metastasis, advanced clinical stage, and reduced survival[23]. Therefore, ST6GAL1 may function as a potential cancer-associated glycosyltransferase in TC, providing valuable insights into its diagnostic and prognostic significance.

4.1.2 Mechanisms in FTC

FTC is the second most common form of TC, responsible for nearly 10-15% of all thyroid malignancies. Patients with FTC generally have good prognosis, despite more aggressive biological behaviors of this clinical phenotype compared to PTC[35]. Miao et al. discovered high expression of ST6GalNAc2 in FTC cells, which might boost tumor invasion by modulating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway[36]. Xu et al. demonstrated enhanced FTC tumorigenesis after aberrant overexpression of ST6GAL2 in both in vivo and in vitro models by inhibiting the Hippo signaling pathway, which could be reversed effectively by resveratrol, a common anti-cancer compound[23]. Additionally, miR-4299 has been shown to modulate the invasive potential of human FTC cells by targeting ST6GALNAC4, both in vivo and in vitro[37].

4.2 Regulation of Immune Response in DTC

Elevated levels of sialylation in tumor cells can enhance the presentation of sialylated ligands such as Mucin proteins (e.g., MUC1), CD24, and sialylated IgG on the cell surface, further facilitating their interactions with specific receptors known as Siglecs[38-41]. Siglecs, belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily, are a class of glycan-binding proteins on cell surface. Their primary function is the selective recognition and binding of sialylated glycans. Through this ligand-receptor interaction, sialylated ligands on tumor cells can engage Siglecs expressed on immune cells, leading to immune tolerance, suppression of anti-tumor immunity, and facilitation of tumor progression[42].

4.2.1 Siglec-Mediated Mechanisms

To date, research has identified a total of 15 types of Siglec receptors. Tumor cells express Siglec ligands, such as CD24, which specifically bind to Siglec-10 receptors on immune cells. This interaction can transmit inhibitory signals that prevent macrophages from phagocytosing tumor cells, thereby promoting immune evasion and facilitating the malignant progression of tumors[43]. Siglecs 7, 9, 10, and 15 are generally detected to be expressed on myeloid cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, monocytes, and neutrophils. By interacting with sialic acids, these Siglecs can interfere with the function of these immune cells, affecting cell differentiation, polarization, phagocytic ability, and immune activation, thereby contributing to immune evasion in tumors[44]. Additionally, the Siglec family may modulate the function of dendritic cells by suppressing their antigen-presenting capability, thereby weakening the initiation of specific immune responses[45].

Roles of STs and NEUs in malignant tumor types

| Functions | Related enzymes* |

|---|---|

| Immune suppression or immune evasion | ST3GAL1[87-90]; ST3GAL3[70]; ST3GAL4[91]; ST6GAL1[92]; ST6GALNAC4[93,94]; ST8SIA4[95]; ST8SIA6[96]; NEU1[97] |

| Induction of EMT signaling pathways | ST6GALNAC1[98]; ST3GAL4[99]; ST3GAL5[100]; ST6GALNAC3[101]; NEU1[65] |

| Regulation of EGFR signaling | ST6GAL1[102]; ST3GAL6[103]; NEU4[104] |

| Regulation of immune cell infiltration | ST3GAL5[105]; ST6GAL1[106]; ST6GAL2[107]; ST8SIA1[108] |

| Mediation of cell-surface sialylation | ST6GAL1[109-113]; ST6GALNAC6[114]; ST8SIA1[115]; ST8SIA2[116]; NEU4[117] |

| Activation of FAK/AKT related signaling pathways | ST8SIA1[118,119]; ST6GALNAC1[120] |

| Regulation of CD8+ T cell function | ST3GAL5[121]; ST8SIA1[122] |

| Induction of cell death | ST6GALNAC6[123]; NEU2[124] |

| Promotion of the malignant biological behaviors | ST3GAL2[125]; ST6GAL1[126,127]; ST6GALNAC5[128]; ST8SIA4[129]; ST8SIA5[130] |

| Other signaling pathways | ST3GAL1: Inhibits CAR-T cells[131]; Activates the NF-κB signaling pathway[132]; ST3GAL4: Enhances glycolysis[133]; Activates MET signaling pathways[134]; ST6GAL1: Induces drug resistance[135]; Activates the cGMP/PKG pathway[136]; ST6GALNAC2: DNA repair pathway[137]; ST6GALNAC4: Activates the TGF pathway[138]; resists NK cell cytotoxicity[139]; ST8SIA1: Blocks JAK/STAT signaling pathways[140]; Enhances the Ap2α-MMP9 axis[141] ST8SIA3: Increases A2B5 expression on the cell surface[142]; NEU3: Activates ERK and PI3K signaling[143] |

*Literature within the latest five years

4.2.2 Evidence from PTC Studies

In PTC cells, Maggisano et al. reported upregulated expression of Siglec-10 and Siglec-11 in PTC cell-derived exosomes, thereby modulating the function of immune cells[46]. Therefore, the molecular profiling of exosomes may provide valuable insights into monitoring the TME and studying the pathogenesis of TC. Huang et al. demonstrated the role of Siglec-15 in promoting TC cell migration by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway through the epidermal growth factor receptor[47]. Jin et al. observed higher expression of Siglec-10 in tumor cells than that in normal tissue cells. Furthermore, co-expression of Siglec-10 and Siglec-15 in tumor cells significantly increased the risk of recurrence in PTC patients, indicating that both factors could serve as important prognostic markers and potential targets for immunotherapy in TC[48]. Additionally, by binding to Siglec-10 on macrophages, CD24 on the surface of TC cells would aid tumor cells in escaping immune surveillance[49].

Furthermore, sialic acids were examined with higher levels on the thyroid globulin antibody IgG1 in PTC patients when compared with Graves' disease patients and healthy controls. By modulating the binding of the antibody's Fc region to Fcγ receptors, this modification of sialic acids may regulate antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and other immune effector functions[50].

However, there is currently a lack of large-scale and systemic clinical data as well as animal models to elucidate the role of sialylation in the malignant progression of DTC. So far, we know little about the specific mechanisms, functions, and clinical significance of sialylation-related targets in DTC. Consequently, it is of great significance to further investigate into the expression, function, and interplay of sialylation-related molecules and immune evasion in PTC, thereby facilitating the elucidation of novel targets and strategies for immunotherapy in DTC.

4.3 Sialylation in Other Types of TC

Currently, researchers also focus on exploring the expression and role of sialylation in other types of TC, in addition to DTC. Preliminary studies have highlighted the potential involvement and the clinical significance of sialylation in these tumors, further supporting its value as a tumor biomarker and laying a foundation for future in-depth research.

4.3.1 Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (MTC)

MTC originates from thyroid C cells, also known as parafollicular cells, which is characterized by high invasiveness, metastatic potential, and a complex genetic background[51]. So far, there is a scarcity of research on unveiling the relationship between sialylation and MTC. Specifically, Komminoth et al. demonstrated specific expression of poly-sialic acid in MTC, suggesting it as a potential marker for distinguishing MTC from other thyroid tumors[52]. Lewis antigens, such as sLeᵃ and sLeˣ, are a class of glycosylated antigens found on carbohydrate molecules, which are associated with the development and progression of tumor cells[53,54]. Vierbuchen et al. further revealed that sialic acids on the outermost layer of MTC tumor cells would mask the Lewis antigens, which would otherwise be recognized by the immune system, highlighting the immune-suppressive role of sialic acids in MTC[55]. This masking effect could reduce the exposure of tumor-associated carbohydrate antigens, impair immune cell recognition, and might contribute to evasion from natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

4.3.2 Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma (ATC)

Typically, ATC is highly proliferative, invasive and metastatic, which is an extremely aggressive and poorly prognostic form of TC[56]. ATC cells with elevated Siglec-15 expression exhibited a higher frequency of interactions with TME cells, further enabling tumor cells to communicate with T cells through immune-suppressive signals. Notably, blocking Siglec-15 would increase the secretion of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) both in vitro and in vivo, significantly inhibiting tumor growth[57]. Hou et al. suggested that Siglec-15 could act as a novel immune checkpoint in TC, promoting cell growth via activating the STAT1/STAT3 signaling pathway, which subsequently enhanced immune suppression. STAT1 and STAT3 are key intracellular signaling molecules that regulate cell proliferation, survival, and immune responses. In addition, silencing Siglec-15 notably inhibited TC cell proliferation and induced apoptosis, presenting a promising therapeutic approach for TC treatment[58]. Thus, high expression of Siglec-15 in ATC exhibits an intimate association with tumor invasiveness, immune evasion, and poor prognosis, providing a solid theoretical foundation for developing strategies targeting Siglec-15 for immune therapy of this disease phenotype.

5. The Application of Sialylation in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Thyroid Carcinoma

As previously mentioned, sialylation has been recognized to be a significant pattern of glycan modification, which has established relationship with tumorigenesis, progression, invasiveness, and metastasis. It also holds potential application value in diagnosing and treating TC, as demonstrated in the following aspects.

5.1 Diagnostic Applications of Sialylation

Advanced techniques, such as mass spectrometry and glycan microarrays, can facilitate the effective detection of different types of sialic acid linkages (e.g. α-2,3 or α-2,6), as well as monitoring of changes in their distribution and abundance across glycan structures[59,60]. These methods are invaluable for exploring the glycosylation profiles of TC tissues and their secretions, enabling precise analysis of the molecular patterns of sialylation. Existing evidence has highlighted the pivotal role of sialylation in differentiating benign from malignant thyroid nodules, and predicting lymph node metastasis[34]. As previously discussed, various STs and Siglecs are crucial molecular biomarkers for predicting TC.

Through a comprehensive analysis of plasma N-glycan alterations in patients with TC and benign thyroid nodules (BTN), Zhang et al. identified distinct differences in plasma N-glycomics between BTN, TC, and healthy controls. It consisted of variations in sialylation levels, and this study also constructed a prediction model, based on four potential biomarkers, to assess the risk of lymph node metastasis in TC patients[34]. Furthermore, Wallace et al. observed significantly lower relative abundance of N-glycans in TC tissues than that in normal thyroid tissues, potentially attributable to impaired N-glycosylation of key proteins such as thyroglobulin. Moreover, there was an escalated relative abundance of sialylated N-glycans in TC, particularly those with α-2,6 sialic acid linkages. This enrichment potentially correlated with enhanced tumor invasiveness and metastatic potential[59]. Collectively, the aforementioned findings suggest that alterations in sialylation status may serve as a valuable adjunctive diagnostic marker for TC.

5.2 Prognostic Implications of Sialylation

The level of sialylation has been reported to have a close link to patient prognosis. Cao et al. observed differences in serum N-glycomics between patients with postoperative surveillance (PS) and postoperative recurrence (PR), further confirming the indicative role of two specific glycan structures (H4N3F1L1 and H4N6F1E1) for sialylation levels in specific linkage types. These structures were found to be upregulated in patients with PR after thyroidectomy and downregulated in those without recurrence (PS), demonstrating their high predictive value for PR of TC[61]. Liu et al. proposed that the accumulation of sialic acids on cancer cell surfaces was a key factor influencing the morphology and invasiveness of diffuse versus non-diffuse tumor types. This hypothesis has been validated in gastric, breast, prostate, and lung cancers, which can be further applicable to other tumor types, such as DSVPTC[62]. As a result, the accumulation of sialic acids on tumor cell surfaces reveals potential correlation with tumor prognosis.

5.3 Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Sialylation

Great concern has been attached to the critical role of sialylation in tumor pathogenesis. Consequently, research on sialylation may both deepen our understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms of tumors, and offer potential anti-tumor therapeutic targets. Kaptan et al. identified that plant lectins (e.g., MAL, SNA, and AAL) might influence tumor cell survival, proliferation, migration, and interactions with endothelial cells by specifically targeting sialic acid-rich α-2,6 and α-2,3 glycan structures on the surface of TC cells[63].

Beyond ST inhibitors, other strategies such as sialidase (neuraminidase) therapy and Siglec-targeting monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are emerging as promising approaches. Sialidase enzymes, such as NEU1, NEU2, NEU3, and NEU4, can desialylate tumor cell surfaces, reducing hypersialylation and enhancing immune recognition[64]. For instance, in TC, sialidase treatment may reverse immune evasion by exposing tumor-associated antigens and improving T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity[65,66]. However, off-target effects, enzymatic stability and other similar challenges may hinder the application of sialidases[67]. Siglec mAbs, such as anti-Siglec-15 or anti-Siglec-10 antibodies, can block inhibitory signals on immune cells to restore the anti-tumor immunity. In ATC, anti-Siglec-15 mAbs have shown potential in increasing IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion to inhibit tumor growth[57]. Advantages of Siglec mAbs include high specificity and synergy with existing immunotherapies, but disadvantages are potential autoimmune reactions and the need for precise targeting to avoid immune-related adverse events[68].

Combination therapy is emerging as a key direction in future cancer immunotherapy. Noticeably, the efficacy of immune treatments can be further enhanced by combining sialylation with other immune therapies (e.g. immune checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cell therapy). This approach may boost the immunogenicity of tumor cells while weakening their ability to evade immune surveillance[69-72].

The necessity of targeting sialylation in TC is underscored by current treatment obstacles, such as radioiodine resistance in differentiated TC, dedifferentiation, and immune suppression in advanced cases. Sialylation-targeted strategies may contribute to overcoming these by re-sensitizing tumors to therapy, inhibiting metastasis, and reversing immune evasion. For example, in PTC, ST6GAL1 inhibition may reduce lymph node metastasis[23], while in ATC, Siglec-15 blockade enhances immune responses[57]. However, corresponding clinical translation requires further validation due to sparse TC-specific studies.

Inhibiting sialylation, targeting sialylated glycans, and modulating immune responses to these glycans can pave the way for innovative diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, thereby improving anti-tumor therapeutic efficacy. Currently, several sialylation-related targeted therapeutic agents, ST inhibitors in particular, are under investigation. These compounds, structurally related to sialic acid donors, receptor substrates, or dual donor-receptor substrates, transition-state analogs, natural products, bile acids, and flavonoids, can specifically inhibit the sialylation of glycoproteins or glycolipids mediated by STs[73-75]. This blockade of the sialic acid recognition pathway can mitigate the malignant biological behaviors of tumors, such as proliferation and invasion[76]. Research on ST inhibitors has already been applied to breast cancer, melanoma, lung cancer and other malignant tumors[77-80]. However, given a sparse studies on TC, its clinical applications remain limited and require further investigation and validation.

6. Conclusions

Currently, there has been great progression in methods for detecting sialylation with the continuous advancement in biomedicine, encompassing techniques such as gas/liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, high-performance liquid chromatography, and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry[81,82]. Significantly, sialylation has been documented to have intimate associations with the invasiveness, metastasis, and immune regulation in various malignant tumors. However, research on the relationship between sialylation and TC is still in its infancy, with limited studies and relatively insufficient exploration. Current investigations primarily focused on alterations in sialylation expression on TC cell surfaces and its correlation with tumor biological behaviors. There is a poor understanding of the specific mechanisms, pathways, and clinical significance of sialylation in TC. For instance, we know little about the precise molecular signaling pathways and regulatory networks although sialylation has been confirmed to affect TC cell adhesion, migration, and invasiveness. Furthermore, more thorough investigation is also necessitated to unveil the role of sialylation in immune evasion in TC and its interactions with the TME. Therefore, there is a pressing need for more systematic and in-depth basic research, along with clinical validation, to explore the mechanisms of sialylation in TC and its potential value in diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis assessment. Such research may provide fresh insights and scientific evidence for precision medicine in TC, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies, thereby improving the prognosis and survival of TC patients.

Abbreviations

TC: thyroid carcinoma; PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma; FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma; DTC: differentiated thyroid carcinoma; PDTC: poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma; ATC: anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; MTC: medullary thyroid carcinoma; TSA: total sialic acids; STs: sialyltransferases; NEUs: neuraminidases; TME: tumor microenvironment; DSVPTC: diffuse sclerosing variant of PTC; HEVs: high endothelial venules; FVPTC: follicular variant of PTC; BTN: benign thyroid nodules; PS: postoperative surveillance; PR: postoperative recurrence; sLeX: sialyl Lewis X; sLeA: sialyl Lewis A; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; AKT: protein kinase B; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; Siglecs: sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins; CMP-Neu5Ac: cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid; UDP-GlcNAc: uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine; ManNAc: N-acetylmannosamine; STAT1/STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 1/3; IFN-γ: interferon gamma; IL-2: interleukin-2; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography; MALDI-TOF-MS: matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry; EMT: epithelial—mesenchymal transition; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; CTCs: circulating tumor cells; ADM: acinar to ductal metaplasia.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20241140), the Doctoral Program for Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Jiangsu province (JSSCBS20221836), and Jiangsu Province Capability Improvement Project through Science, Technology and Education (Jiangsu Provincial Medical Key Discipline, ZDXK202222).

Author contributions

Original idea, planning and writing: Chengyuan Li and Jianing Zhou. Searching for resources: Lijun Zhang and Yan Si. Reviewing and editing: Xiang Zhang and Meiping Shen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229-263

2. Boucai L, Zafereo M, Cabanillas ME. Thyroid cancer: a review. Jama. 2024;331(5):425-435

3. Chen DW, Lang BHH, Mcleod DSA. et al. Thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2023;401(10387):1531-1544

4. Wang S, Osgood AO, Chatterjee A. Uncovering post-translational modification-associated protein-protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2022;74:102352

5. Pan S, Chen R. Pathological implication of protein post-translational modifications in cancer. Mol Aspects Med. 2022;86:101097

6. Wang Y, Zuo J, Chen C. et al. Post-translational modifications and immune responses in liver cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1230465

7. čaval T, Alisson-Silva F, Schwarz F. Roles of glycosylation at the cancer cell surface: opportunities for large scale glycoproteomics. Theranostics. 2023;13(8):2605-2615

8. Pietrobono S, Stecca B. Aberrant sialylation in cancer: biomarker and potential target for therapeutic intervention? Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(9):2014

9. Li F, Ding J. Sialylation is involved in cell fate decision during development, reprogramming and cancer progression. Protein Cell. 2019;10(8):550-565

10. Munkley J. Aberrant sialylation in cancer: therapeutic opportunities. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(17):4248-4270

11. Filipsky F, Läubli H. Regulation of sialic acid metabolism in cancer. Carbohydr Res. 2024;539:109123

12. Blix G. Über die kohlenhydratgruppen des submaxillarismucins. Biol Chem. 1936;1-2(240):43-54

13. Klenk E. Neuraminsäure, das spaltprodukt eines neuen gehirnlipoids. Biol Chem. 1941;1-2(268):50-58

14. Blix FG, Gottschalk A, Klenk E. Proposed nomenclature in the field of neuraminic and sialic acids. Nature. 1957;179(4569):1088

15. Li D, Lin Q, Luo F. et al. Insights into the structure, metabolism, biological functions and molecular mechanisms of sialic acid: a review. Foods. 2024;13(1):145-165

16. Dobie C, Skropeta D. Insights into the role of sialylation in cancer progression and metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(1):76-90

17. Zhou X, Yang G, Guan F. Biological functions and analytical strategies of sialic acids in tumor. Cells. 2020;9(2):273-290

18. Zhou X, Chi K, Zhang C. et al. Sialylation: a cloak for tumors to trick the immune system in the microenvironment. Biology (Basel). 2023;12(6):832-852

19. Vattepu R, Sneed SL, Anthony RM. Sialylation as an important regulator of antibody function. Front Immunol. 2022;13:818736

20. Lee D, Kang S, Choi D. et al. Genome wide CRISPR screening reveals a role for sialylation in the tumorigenesis and chemoresistance of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cancer Lett. 2021;510:37-47

21. Harduin-Lepers A, Vallejo-Ruiz V, Krzewinski-Recchi M. et al. The human sialyltransferase family. Biochimie. 2001;83(8):727-737

22. Kokoglu E, Uslu E, Uslu I. et al. Serum and tissue total sialic acid as a marker for human thyroid cancer. Cancer Lett. 1989;46(1):1-5

23. Gunjaca I, Benzon B, Pleic N. et al. Role of ST6GAL1 in thyroid cancers: insights from tissue analysis and genomic datasets. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(22):16334

24. Xu G, Chen J, Wang G. et al. Resveratrol inhibits the tumorigenesis of follicular thyroid cancer via ST6GAL2-regulated activation of the hippo signaling pathway. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;16:124-133

25. Hugonnet M, Singh P, Haas Q. et al. The distinct roles of sialyltransferases in cancer biology and onco-immunology. Front Immunol. 2021;12:799861

26. Nag S, Mandal A, Joshi A. et al. Sialyltransferases and neuraminidases: potential targets for cancer treatment. Diseases. 2022;10(4):114-136

27. Bowles WHD, Gloster TM. Sialidase and sialyltransferase inhibitors: targeting pathogenicity and disease. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:705133

28. Grewal RK, Shaikh AR, Gorle S. et al. Structural insights in mammalian sialyltransferases and fucosyltransferases: we have come a long way, but it is still a long way down. Molecules. 2021;26(17):5203-5225

29. Babál P, Janega P, černá A. et al. Neoplastic transformation of the thyroid gland is accompanied by changes in cellular sialylation. Acta Histochem. 2006;108(2):133-140

30. Jiang M, Fang H, Tian H. Metabolism of cancer cells and immune cells in the initiation, progression, and metastasis of cancer. Theranostics. 2025;15(1):155-188

31. Cai K, Chen Q, Shi D. et al. Sialylation-dependent interaction between PD-l1 and CD169 promotes monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. Glycobiology. 2023;33(3):215-224

32. Bai J, Xiao R, Jiang D. et al. Sialic acids: sweet modulators fueling cancer cells and domesticating the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2025;626:217773

33. Low S, Sakai Y, Hoshino H. et al. High endothelial venule-like vessels and lymphocyte recruitment in diffuse sclerosing variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Pathology. 2016;48(7):666-674

34. Zhang Z, Reiding KR, Wu J. et al. Distinguishing benign and malignant thyroid nodules and identifying lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer by plasma n -glycomics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:692910

35. Yamazaki H, Sugino K, Katoh R. et al. Management of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Eur Thyroid J. 2024;13(5):e240146

36. Miao X, Zhao Y. ST6GalNAcII mediates tumor invasion through PI3k/akt/NF-kappab signaling pathway in follicular thyroid carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(4):2131-2140

37. Miao X, Jia L, Zhou H. et al. Mir-4299 mediates the invasive properties and tumorigenicity of human follicular thyroid carcinoma by targeting ST6GALNAC4. IUBMB Life. 2016;68(2):136-144

38. J M, Sanji AS, Gurav MJ. et al. Overexpression of sialyl lewis(a) carrying mucin-type glycoprotein in prostate cancer cell line contributes to aggressiveness and metastasis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;281(Pt 4):136519

39. He J, Zhang F, Wu B. et al. ST8SIA6 sialylates CD24 to enhance its membrane localization in BRCA. Cells. 2024;14(1):9-26

40. Cui M, Shoucair S, Liao Q. et al. Cancer-cell-derived sialylated IgG as a novel biomarker for predicting poor pathological response to neoadjuvant therapy and prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Int J Surg. 2023;109(2):99-106

41. Wang Z, Geng Z, Shao W. et al. Cancer-derived sialylated IgG promotes tumor immune escape by binding to siglecs on effector t cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(11):1148-1162

42. Stanczak MA, Rodrigues Mantuano N, Kirchhammer N. et al. Targeting cancer glycosylation repolarizes tumor-associated macrophages allowing effective immune checkpoint blockade. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(669):eabj1270

43. Li X, Tian W, Jiang Z. et al. Targeting CD24/siglec-10 signal pathway for cancer immunotherapy: recent advances and future directions. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024;73(2):31

44. Boelaars K, van Kooyk Y. Targeting myeloid cells for cancer immunotherapy: siglec-7/9/10/15 and their ligands. Trends Cancer. 2024;10(3):230-241

45. Wang J, Manni M, Bärenwaldt A. et al. Siglec receptors modulate dendritic cell activation and antigen presentation to t cells in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:828916

46. Maggisano V, Capriglione F, Mio C. et al. RNA profile of cell bodies and exosomes released by tumorigenic and non-tumorigenic thyroid cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(3):1407

47. Huang S, Ji Z, Xu J. et al. Siglec15 promotes the migration of thyroid carcinoma cells by enhancing the EGFR protein stability. Glycobiology. 2023;33(6):464-475

48. Jin T, Wang W, Ge L. et al. The expression of two immunosuppressive SIGLEC family molecules in papillary thyroid cancer and their effect on prognosis. Endocrine. 2023;82(3):590-601

49. Zhang F, Xu P, Zhang L. et al. RARγ promotes the invasion and metastasis of thyroid carcinoma by activating the JAK1-STAT3-CD24/MMPs axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;125(Pt A):111129

50. Li Y, Zhao C, Zhao K. et al. Glycosylation of anti-thyroglobulin IgG1 and IgG4 subclasses in thyroid diseases. Eur Thyroid J. 2021;10(2):114-124

51. Zhang Y, Zheng W, Zhou S. et al. Molecular genetics, therapeutics and RET inhibitor resistance for medullary thyroid carcinoma and future perspectives. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22(1):460-486

52. Komminoth P, Roth J, Saremaslani P. et al. Polysialic acid of the neural cell adhesion molecule in the human thyroid: a marker for medullary thyroid carcinoma and primary c-cell hyperplasia. An immunohistochemical study on 79 thyroid lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(4):399-411

53. Yan L, Sundaram S, Rust BM. et al. Metabolomes of lewis lung carcinoma metastases and normal lung tissue from mice fed different diets. J Nutr Biochem. 2022;107:109051

54. Rabassa ME, Pereyra A, Pereyra L. et al. Lewis x antigen is associated to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma survival. Pathol Oncol Res. 2018;24(3):525-531

55. Vierbuchen M, Schroder S, Larena A. et al. Native and sialic acid masked lewis(a) antigen reactivity in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Distinct tumour-associated and prognostic relevant antigens. Virchows Arch. 1994;424(2):205-211

56. Rao SN, Smallridge RC. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: an update. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;37(1):101678

57. Bao L, Li Y, Hu X. et al. Targeting SIGLEC15 as an emerging immunotherapy for anaplastic thyroid cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;133:112102

58. Hou X, Chen C, He X. et al. Siglec-15 silencing inhibits cell proliferation and promotes cell apoptosis by inhibiting STAT1/STAT3 signaling in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:1606404

59. Wallace EN, West CA, Mcdowell CT. et al. An n-glycome tissue atlas of 15 human normal and cancer tissue types determined by MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):489-503

60. Pazitna L, Nemcovic M, Pakanova Z. et al. Influence of media composition on recombinant monoclonal IgA1 glycosylation analysed by lectin-based protein microarray and MALDI-MS. J Biotechnol. 2020;314-315:34-40

61. Cao Z, Zhang Z, Liu R. et al. Serum linkage-specific sialylation changes are potential biomarkers for monitoring and predicting the recurrence of papillary thyroid cancer following thyroidectomy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:858325

62. Liu D, Xing F, Wang Y. et al. Molecular bases of morphologically diffused tumors across multiple cancer types. Natl Sci Rev. 2022;9(11):177-179

63. Kaptan E, Sancar-Bas S, Sancakli A. et al. The effect of plant lectins on the survival and malignant behaviors of thyroid cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(7):6274-6287

64. Yang Z, Hou Y, Grande G. et al. Targeted desialylation and cytolysis of tumour cells by fusing a sialidase to a bispecific t-cell engager. Nat Biomed Eng. 2024;8(5):499-512

65. Peng Q, Gao L, Cheng HB. et al. Sialidase NEU1 may serve as a potential biomarker of proliferation, migration and prognosis in melanoma. World J Oncol. 2022;13(4):222-234

66. Nath S, Mondal S, Butti R. et al. Desialylation of sonic-hedgehog by neu2 inhibits its association with patched1 reducing stemness-like properties in pancreatic cancer sphere-forming cells. Cells. 2020;9(6):1512-1534

67. Farrell RE, Stelzer KA, Liu G. et al. Emerging role of sialylation in cancer therapy resistance: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Drug Resist Updat. 2025;83:101285

68. Mccord KA, Macauley MS. Transgenic mouse models to study the physiological and pathophysiological roles of human siglecs. Biochem Soc Trans. 2022;50(2):935-950

69. Wu R, Lao X, Chen D. et al. Immune checkpoint therapy-elicited sialylation of IgG antibodies impairs antitumorigenic type i interferon responses in hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunity. 2023;56(1):180-192

70. Cao K, Zhang G, Yang M. et al. Attenuation of sialylation augments antitumor immunity and improves response to immunotherapy in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2023;83(13):2171-2186

71. Wen RM, Stark JC, Marti GEW. et al. Sialylated glycoproteins suppress immune cell killing by binding to siglec-7 and siglec-9 in prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2024;134(24):e180282

72. Ding M, Lin J, Qin C. et al. Novel CAR-t cells specifically targeting SIA-CIgG demonstrate effective antitumor efficacy in bladder cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(40):e2400156

73. Dobie C, Montgomery AP, Szabo R. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of selective phosphonate-bearing 1,2,3-triazole-linked sialyltransferase inhibitors. RSC Med Chem. 2021;12(10):1680-1689

74. Szabo R, Dobie C, Montgomery AP. et al. Synthesis of alpha-hydroxy-1,2,3-triazole-linked sialyltransferase inhibitors and evaluation of selectivity towards ST3GAL1, ST6GAL1 and ST8SIA2. ChemMedChem. 2024;19(16):e202400088

75. Perez SJLP, Chen C, Chang T. et al. Biological evaluation of sulfonate and sulfate analogues of lithocholic acid: a bioisosterism-guided approach towards the discovery of potential sialyltransferase inhibitors for antimetastatic study. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2024;105:129760

76. Perez SJLP, Fu C, Li W. Sialyltransferase inhibitors for the treatment of cancer metastasis: current challenges and future perspectives. Molecules. 2021;26(18):5673

77. Tsai H, Chen C, Chang T. et al. Development of a novel, potent, and selective sialyltransferase inhibitor for suppressing cancer metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(8):4283

78. Fu C, Tsai H, Chen W. et al. Sialyltransferase inhibitors suppress breast cancer metastasis. J Med Chem. 2021;64(1):527-542

79. Chen J, Tang Y, Huang S. et al. A novel sialyltransferase inhibitor suppresses FAK/paxillin signaling and cancer angiogenesis and metastasis pathways. Cancer Res. 2011;71(2):473-483

80. Su M, Chang T, Chiang C. et al. Inhibition of chemokine (c-c motif) receptor 7 sialylation suppresses CCL19-stimulated proliferation, invasion and anti-anoikis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98823

81. Koçak ÖF, Kayili HM, Albayrak M. et al. N-glycan profiling of papillary thyroid carcinoma tissues by MALDI-TOF-MS. Anal Biochem. 2019;584:113389

82. Zhang Y, Zhao W, Zhao Y. et al. Comparative glycoproteomic profiling of human body fluid between healthy controls and patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2020;19(7):2539-2552

83. Habeeb IF, Alao TE, Delgado D. et al. When a negative (charge) is not a positive: sialylation and its role in cancer mechanics and progression. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1487306

84. Kindt N, Journe F, Ghanem GE. et al. Galectins and carcinogenesis: their role in head and neck carcinomas and thyroid carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2745

85. Ma B, Jiang H, Wen D. et al. Transcriptome analyses identify a metabolic gene signature indicative of dedifferentiation of papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(9):3713-3725

86. Li X, Liu D, Wu Z. et al. Diffuse tumors: molecular determinants shared by different cancer types. Comput Biol Med. 2024;178:108703

87. Garnham R, Geh D, Nelson R. et al. ST3 beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase 1 (ST3gal1) synthesis of siglec ligands mediates anti-tumour immunity in prostate cancer. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):276-288

88. Lin W, Fan T, Hung J. et al. Sialylation of CD55 by ST3GAL1 facilitates immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9(1):113-122

89. Zou Y, Guo S, Liao Y. et al. Ceramide metabolism-related prognostic signature and immunosuppressive function of ST3GAL1 in osteosarcoma. Transl Oncol. 2024;40:101840

90. Rodriguez E, Boelaars K, Brown K. et al. Sialic acids in pancreatic cancer cells drive tumour-associated macrophage differentiation via the siglec receptors siglec-7 and siglec-9. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1270

91. Krishnamoorthy V, Daly J, Kim J. et al. The glycosyltransferase ST3GAL4 drives immune evasion in acute myeloid leukemia by synthesizing ligands for the glyco-immune checkpoint receptor siglec-9. Leukemia. 2024;39(2):346-359

92. Hodgson K, Orozco-Moreno M, Goode EA. et al. Sialic acid blockade inhibits the metastatic spread of prostate cancer to bone. EBioMedicine. 2024;104:105163

93. Dai T, Li J, Liang R. et al. Identification and experimental validation of the prognostic significance and immunological correlation of glycosylation-related signature and ST6GALNAC4 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2023;10:531-551

94. Smith BAH, Deutzmann A, Correa KM. et al. MYC-driven synthesis of siglec ligands is a glycoimmune checkpoint. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(11):e2215376120

95. Shu X, Li J, Chan UI. et al. BRCA1 insufficiency induces a hypersialylated acidic tumor microenvironment that promotes metastasis and immunotherapy resistance. Cancer Res. 2023;83(15):2614-2633

96. Friedman DJ, Crotts SB, Shapiro MJ. et al. ST8sia6 promotes tumor growth in mice by inhibiting immune responses. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9(8):952-966

97. Wu Z, He L, Yang L. et al. Potential role of NEU1 in hepatocellular carcinoma: a study based on comprehensive bioinformatical analysis. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:651525

98. Luo Y, Cao H, Lei C. et al. ST6GALNAC1 promotes the invasion and migration of breast cancer cells via the EMT pathway. Genes Genomics. 2023;45(11):1367-1376

99. Zheng W, Zhang H, Huo Y. et al. The role of ST3GAL4 in glioma malignancy, macrophage infiltration, and prognostic outcomes. Heliyon. 2024;10(9):e29829

100. Zhang J, van der Zon G, Ma J. et al. ST3GAL5-catalyzed gangliosides inhibit TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via TbetaRI degradation. Embo J. 2023;42(2):e110553

101. Dai J, Li Q, Quan J. et al. Construction of a lipid metabolism-related and immune-associated prognostic score for gastric cancer. BMC Med Genomics. 2023;16(1):93-108

102. Ankenbauer KE, Rao TC, Mattheyses AL. et al. Sialylation of EGFR by ST6GAL1 induces receptor activation and modulates trafficking dynamics. J Biol Chem. 2023;299(10):105217

103. Li J, Long Y, Sun J. et al. Comprehensive landscape of the ST3GAL family reveals the significance of ST3GAL6-as1/ST3GAL6 axis on EGFR signaling in lung adenocarcinoma cell invasion. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:931132

104. Shi J, Zhou R, Wang S. et al. NEU4-mediated desialylation enhances the activation of the oncogenic receptors for the dissemination of ovarian carcinoma. Oncogene. 2024;43(49):3556-3569

105. Jian Y, Chen Q, Al-Danakh A. et al. Identification and validation of sialyltransferase ST3gal5 in bladder cancer through bioinformatics and experimental analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;138:112569

106. Liu R, Cao X, Liang Y. et al. Downregulation of ST6GAL1 promotes liver inflammation and predicts adverse prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:5801-5814

107. Liu R, Yu X, Cao X. et al. Downregulation of ST6GAL2 correlates to liver inflammation and predicts adverse prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Inflamm Res. 2024;17:565-580

108. Hu X, Yang Y, Wang Y. et al. Identifying an immune-related gene ST8SIA1 as a novel target in patients with clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:901518

109. Scott E, Archer Goode E, Garnham R. et al. ST6GAL1 -mediated aberrant sialylation promotes prostate cancer progression. J Pathol. 2023;261(1):71-84

110. Hait NC, Maiti A, Wu R. et al. Extracellular sialyltransferase st6gal1 in breast tumor cell growth and invasiveness. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022;29(11):1662-1675

111. Chen S, He P, Lu L. et al. ST6GAL1-mediated sialylation of PECAM-1 promotes a transcellular diapedesis-like process that directs lung tropism of metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2024;85(7):1199-1218

112. Zou X, Lu J, Deng Y. et al. ST6GAL1 inhibits metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via modulating sialylation of MCAM on cell surface. Oncogene. 2023;42(7):516-529

113. Gc S, Tuy K, Rickenbacker L. et al. Alpha2,6 sialylation mediated by ST6GAL1 promotes glioblastoma growth. JCI Insight. 2022;7(21):e158799

114. Tan Z, Pan K, Sun M. et al. CCKBR+ cancer cells contribute to the intratumor heterogeneity of gastric cancer and confer sensitivity to FOXO inhibition. Cell Death Differ. 2024;31(10):1302-1317

115. Pilgrim AA, Jonus HC, Ho A. et al. The yes-associated protein (YAP) is associated with resistance to anti-GD2 immunotherapy in neuroblastoma through downregulation of ST8SIA1. Oncoimmunology. 2023;12(1):2240678

116. Moe GR, Steirer LM, Lee JA. et al. A cancer-unique glycan: de-n-acetyl polysialic acid (dPSA) linked to cell surface nucleolin depends on re-expression of the fetal polysialyltransferase ST8SIA2 gene. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):293-306

117. Zhang X, Dou P, Akhtar ML. et al. NEU4 inhibits motility of HCC cells by cleaving sialic acids on CD44. Oncogene. 2021;40(35):5427-5440

118. Wan H, Li Z, Wang H. et al. ST8SIA1 inhibition sensitizes triple negative breast cancer to chemotherapy via suppressing wnt/β-catenin and FAK/akt/mTOR. Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(4):902-910

119. Xing P, Wang Y, Zhang L. et al. Knockdown of lncRNA MIR4435-2HG and ST8SIA1 expression inhibits the proliferation, invasion and migration of prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by blocking the activation of the FAK/AKT/β-catenin signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2021;47(6):93-105

120. Khiaowichit J, Talabnin C, Dechsukhum C. et al. Down-regulation of c1GALT1 enhances the progression of cholangiocarcinoma through activation of AKT/ERK signaling pathways. Life (Basel). 2022;12(2):174

121. Liu J, Li M, Wu J. et al. Identification of ST3GAL5 as a prognostic biomarker correlating with CD8+ t cell exhaustion in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:979605

122. Zhang C, Wang Y, Yu Y. et al. Overexpression of ST8sia1 inhibits tumor progression by TGF-β1 signaling in rectal adenocarcinoma and promotes the tumoricidal effects of CD8+ t cells by granzyme b and perforin. Ann Med. 2025;57(1):2439539

123. Wang L, Wu S, He H. et al. CircRNA-ST6GALNAC6 increases the sensitivity of bladder cancer cells to erastin-induced ferroptosis by regulating the HSPB1/p38 axis. Lab Invest. 2022;102(12):1323-1334

124. Satyavarapu EM, Nath S, Mandal C. Desialylation of atg5 by sialidase (neu2) enhances autophagosome formation to induce anchorage-dependent cell death in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7(1):26-41

125. Deschuyter M, Leger DY, Verboom A. et al. ST3GAL2 knock-down decreases tumoral character of colorectal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Am J Cancer Res. 2022;12(1):280-302

126. Dashzeveg NK, Jia Y, Zhang Y. et al. Dynamic glycoprotein hyposialylation promotes chemotherapy evasion and metastatic seeding of quiescent circulating tumor cell clusters in breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023;13(9):2050-2071

127. Bhalerao N, Chakraborty A, Marciel MP. et al. ST6GAL1 sialyltransferase promotes acinar to ductal metaplasia and pancreatic cancer progression. JCI Insight. 2023;8(19):e161563

128. Li M, Ma Z, Zhang Y. et al. Integrative analysis of the ST6GALNAC family identifies GATA2-upregulated ST6GALNAC5 as an adverse prognostic biomarker promoting prostate cancer cell invasion. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):141-159

129. Fu W, Yu G, Liang J. et al. Mir-144-5p and mir-451a inhibit the growth of cholangiocarcinoma cells through decreasing the expression of ST8SIA4. Front Oncol. 2021;10:563486

130. Gong Y, Wu S, Dong S. et al. Development of a prognostic metabolic signature in stomach adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2022;24(8):1615-1630

131. Hong Y, Walling BL, Kim H. et al. ST3GAL1 and βII-spectrin pathways control CAR t cell migration to target tumors. Nat Immunol. 2023;24(6):1007-1019

132. Chen F, Gao K, Li Y. et al. ST3GAL1 promotes malignant phenotypes in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2024;23(9):100821

133. Chen X, Su W, Chen J. et al. ST3GAL4 promotes tumorigenesis in breast cancer by enhancing aerobic glycolysis. Hum Cell. 2025;38(1):1-16

134. Han R, Lin C, Lu C. et al. Sialyltransferase ST3GAL4 confers osimertinib resistance and offers strategies to overcome resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2024;588:216762

135. Smithson M, Diffalha SA, Irwin RK. et al. ST6GAL1 is associated with poor response to chemoradiation in rectal cancer. Neoplasia. 2024;51:100984

136. Wang J, Liu G, Liu M. et al. High-risk HPV16 e6 activates the cGMP/PKG pathway through glycosyltransferase ST6GAL1 in cervical cancer cells. Front Oncol. 2021;11:716246

137. Matejcic M, Shaban HA, Quintana MW. et al. Rare variants in the DNA repair pathway and the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(5):895-903

138. Man D, Jiang Y, Zhang D. et al. ST6GALNAC4 promotes hepatocellular carcinogenesis by inducing abnormal glycosylation. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):420-434

139. Chang L, Liang S, Lu S. et al. Molecular basis and role of siglec-7 ligand expression on chronic lymphocytic leukemia b cells. Front Immunol. 2022;13:840388

140. Yu S, Wang S, Sun X. et al. ST8SIA1 inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of bladder cancer cells by blocking the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2021;22(4):736-746

141. Ohkawa Y, Zhang P, Momota H. et al. Lack of GD3 synthase (st8sia1) attenuates malignant properties of gliomas in genetically engineered mouse model. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(9):3756-3768

142. Baeza-Kallee N, Bergès R, Hein V. et al. Deciphering the action of neuraminidase in glioblastoma models. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14):11645

143. Tatsuta T, Ito J, Yamamoto K. et al. Sialidase NEU3 contributes to the invasiveness of bladder cancer. Biomedicines. 2024;12(1):192-202

Author contact

*![]() Corresponding authors: Meiping Shen, M.D. Department of General Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, No.300 Guangzhou Road, Nanjing, 210029, China. E-mail: shenmeipingorg.cn (M. Shen). Xiang Zhang, M.D. Department of General Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, No. 300 Guangzhou Road, Nanjing, 210029, China. E-mail: zhangxiangedu.cn (X. Zhang).

Corresponding authors: Meiping Shen, M.D. Department of General Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, No.300 Guangzhou Road, Nanjing, 210029, China. E-mail: shenmeipingorg.cn (M. Shen). Xiang Zhang, M.D. Department of General Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, No. 300 Guangzhou Road, Nanjing, 210029, China. E-mail: zhangxiangedu.cn (X. Zhang).

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact