Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2026; 17(2):257-267. doi:10.7150/jca.127496 This issue Cite

Review

Clinical management and therapeutic development for the rare disease rhabdomyosarcoma

1. Institute of Molecular Medicine, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan, No. 101, Section 2, Kuang-Fu Road, Hsinchu, 30013, Taiwan.

2. Department of Medical Science, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan, No. 101, Section 2, Kuang-Fu Road, Hsinchu, 30013, Taiwan.

Received 2025-10-29; Accepted 2025-12-17; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare disease that arises from skeletal muscle mainly affects children and adolescents. Patients with RMS have diverse symptoms and prognosis based on tumor sizes, tumor anatomical locations, histological subtypes of the tumors and genetic testing of paired-box-forkhead box O1 (PAX-FOXO1) fusion gene. The 4 subtypes of RMS include embryonal RMS (eRMS), alveolar RMS (aRMS), spindle cell/sclerosing RMS (scRMS) and pleomorphic RMS (pRMS). Treatment for RMS patients remains challenging due to its heterogeneous nature. Thus, a combinatory approach is likely to warrant better management of RMS. Given that PAX-FOXO1 fusion gene is the most common biomarker for RMS, though this fusion gene only accounts for 16-20% of RMS patients. Targeted therapy that tailors treatment plans to the individual patient may provide additional benefits for RMS patients. This review describes the frequent genetic mutations observed in RMS patients and drug development based on these mutations shall provide direction to develop targeted therapy leading to effective personalized treatment for RMS patients.

Keywords: rhabdomyosarcoma, myogenesis, myoblast fusion, targeted therapy, rare disease

1. Skeletal muscle diseases and related rare diseases

Skeletal muscles are essential for movement, breathing, posture, and overall health. Disorders affecting the skeletal muscle tissue are categorized as musculoskeletal and neuromuscular disorders. Musculoskeletal disorders involve injuries and conditions affecting the skeletal muscles and associated connective tissues such as bones and joints. The symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders include pain, stiffness, limited range of motion, inflammation, and fatigue. Musculoskeletal disorders could also contribute to muscle atrophy including muscular dystrophy, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscular disorders affect the peripheral nerves that control voluntary muscles or neuromuscular junction. Muscular dystrophy results in wasting and loss of muscle tissue, disability and possible deformity. Treatment for muscle atrophy includes regular exercise, physical therapy, medications managing chronic diseases or addressing nutritional deficiencies. Uncontrolled cell growth arising from bones or muscles will lead to musculoskeletal cancers, which are often rare cancers, such as osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), leiomyosarcoma. The treatment for musculoskeletal cancer depends on the sizes, stages and locations of the cancers which usually involves surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Targeted therapy provides more personalized and effective treatment approaches and play an important role in the management of some cancers such as breast cancer, lung cancer and colorectal cancer. Although there is some targeted therapy for osteosarcoma [1, 2], much less is available for musculoskeletal cancer compared to other cancer types.

2. Histological subtypes of RMS

RMS is a rare disease, as defined by Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD), National Institute of Health (NIH). RMS is the most common type of soft tissue sarcoma that malignant cells arising from skeletal muscle, and it primarily affects children and adolescents. Approximately 350 new cases of RMS are diagnosed every year in the United States. Overall incidence is 4.5-6 cases per million people in Europe and United States and 3.5 cases per million in Asia [3]. Although the overall five-year survival rate for RMS in children exceeds 70%, the five-year survival rate of children with RMS that has metastasized to distant parts of the body is less than 30% and patients with recurrent RMS is only 17% [4-6]. Adults with RMS have worse survival than children, with an overall five-year survival rate of only 20% to 40% [7, 8].

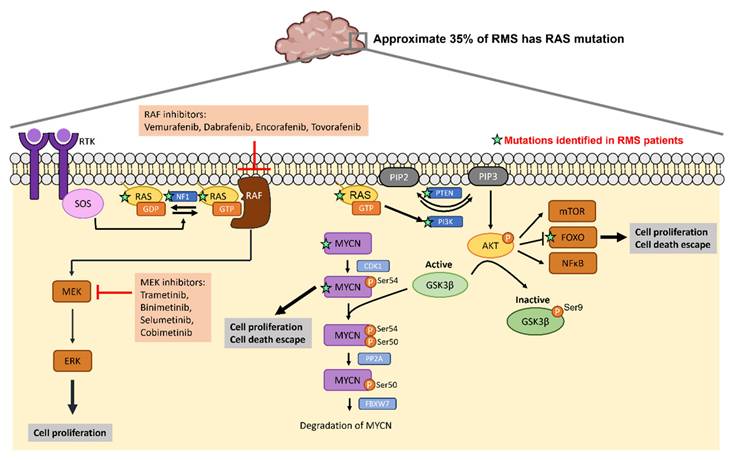

There are 4 histologic subtypes of RMS classified according to the 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone: embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (eRMS), alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (aRMS), spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma (scRMS) and pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma (pRMS) (Figure 1A) [9]. The embryonal subtype is the most frequently observed subtype which account for 70% to 75% of childhood RMS. eRMS is associated with round-cell phenotype and typically arises in the head and neck or genitourinary region in children younger than five. Approximately 20% to 25% of children with RMS have the alveolar subtype. Tumors with alveolar histology usually in extremities, trunk, and perineum/perianal region and have an increased frequency in adolescents and young adults [10]. The scRMS are considered in the same diagnosis spectrum and account for 3% to 10% of all cases, with high frequency at the paratesticular site. The pRMS is an extremely rare subtype characterized by a high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma arises in the extremities in adults [9]. This type of RMS often results in poor prognosis. Additionally, RMS has been further characterized based on molecular biology characteristics of fusion proteins paired-box 3-forkhead box O1 (PAX3-FOXO1) or paired-box 7-FOXO1 (PAX7-FOXO1). Here, fusion-positive (FP) and fusion-negative (FN) were defined [6, 11]. Approximately 80% of patients with the aRMS (16% of all RMS) have chromosomal translocations resulting in FOXO1 gene fusion to PAX3 or PAX7, which is implicated in a poorer prognosis [12, 13]. Fusion between DNA binding domain of PAX3/7 and transactivation domain of FOXO1 drives epigenetic changes and alters hundreds of genes transcription. Several studies have implicated that PAX3/7-FOXO1 fusion protein regulates many downstream factors to suppress cell apoptosis (MYCN) [14], promote cell survival (FGFR4), enhance cell invasion (FGFR4 and IGF2) [15, 16], increase cell proliferation and motility (c-MET, IGF1, CXCR4) [17, 18], drive myogenic determination and repress myogenic differentiation (MYOD, MYOG) [14, 19, 20] (Figure 1B). These PAX3/7-FOXO1-mediated genomic instability is strongly associated with a poor prognosis in FP aRMS [20].

3. Clinical treatments of RMS

Treatment of RMS presents unique challenges due to the scarcity of the disease and various anatomical sites of primary tumor. For optimal management and treatment, patients with RMS require multimodality therapy including surgery, radiation therapy and systemic chemotherapy to ensure receiving ideal treatment, supportive care and rehabilitation to achieve optimal survival and quality of life. [21-23]. Optimizing patient care requires tailored treatment decisions regarding surgical and radiotherapeutic options, which must be based on factors such as patient ages, tumor sizes, histological subtypes and the anatomical locations of tumors. If the tumor resection will not cause dysfunction or deformity, surgical resection is performed first before other treatment. If this is not possible, only an initial biopsy is performed. Radiation therapy is often used for RMS patients with metastasis or the tumors that cannot be completely removed surgically. In order to prevent recurrence or metastasis of RMS, chemotherapy is used after surgery and/or radiation therapy. The standard chemotherapy regimen for patients with RMS is the combination of vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) in North America [24]. In Europe, the chemotherapy regimen is the combination of ifosfamide, vincristine, and actinomycin D (IVA) [6]. Vincristine binds irreversibly to microtubules and spindle proteins in S phase of the cell cycle and thus interferes with the formation of the mitotic spindle, thereby arresting tumor cells in metaphase. Actinomycin D binds to guanine residues in DNA and blocking the action of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase functions thereby inhibit RNA synthesis. Cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide react with DNA to interfere DNA replication and cell division. There are no significant differences in the clinical outcomes between VAC and IVA regimens [25]. Table 1 listed the ongoing or completed clinical trials related to RMS. Most clinical trials focus on the combination of common chemotherapy drugs, while only limited trials test antibody or T cell transplantation application in RMS.

Subtypes of RMS and PAX3/7-FOXO1 fusion protein in FP aRMS. (A) The incidence, tumor location, age group and PAX3/7-FOXO1 fusion gene alteration of different RMS subtypes. (B) The PAX3/7-FOXO1 fusion protein drives epigenetic changes and alters genes transcription, leading to poor prognosis of FP aRMS.

4. Genetic mutations in patients with RMS

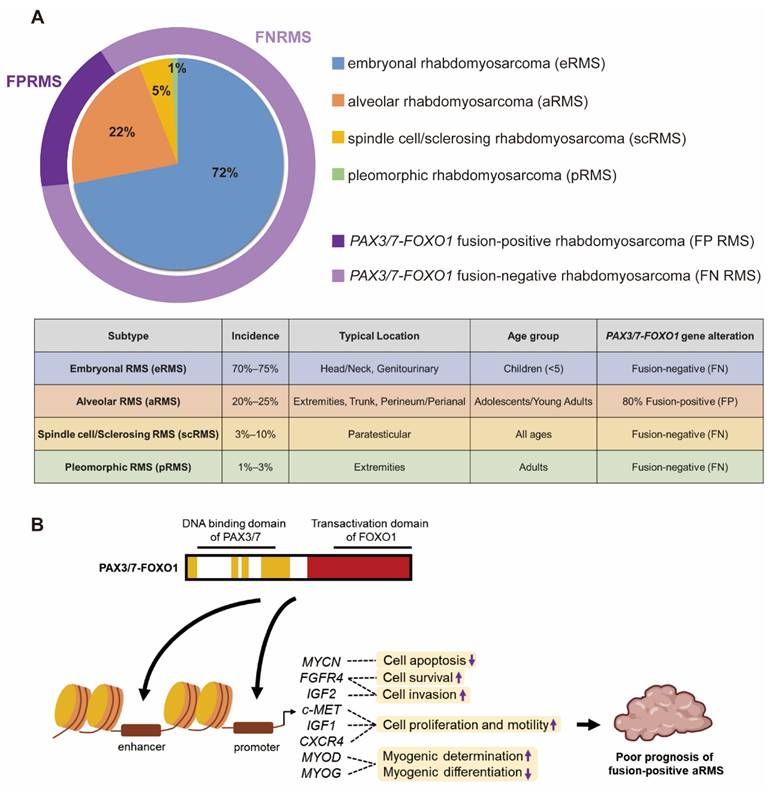

Previous reports have documented the mutations observed in eRMS (28.3%) and aRMS (3.5%) [26]. A wide range of genetic mutations were identified in FN RMS including mutations in NRAS, KRAS, HRAS [27], TP53 [28], PIK3CA, CTNNB1 [26] and FGFR4 [29]. These gene mutations in RMS are associated with more aggressive genotypes and poorer outcomes. Multiple mutations within individual tumors in FN RMS are associated with worse event-free survival [30]. Thus, it is critical to further characterize the genetic events underlying RMS in order to develop more effective diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic strategies. J.F. Shern et al. compared gene mutations between FN and FP RMS patients using a combined cohort of the Children's Oncology Group (COG) and United Kingdom RMS patients (n = 641) [30] (Figure 2). A higher frequency of mutations in NRAS, BCOR and NF1 genes was observed in patients with FN RMS while mutations in CDK4 and MYCN are more common in patients with FP RMS. The differential frequency of gene mutations between FN and FP RMS may provide direction in developing personalized medical approaches.

Ongoing or completed clinical trials related to RMS

| NCT number (Registration Date) | Title | Phase# | Status | Study completion date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01355445 (2011-05-16) | Vincristine and Irinotecan with or Without Temozolomide in Children and Adults with Refractory/Relapsed Rhabdomyosarcoma (VIT-0910) | 2 | Completed | 2019-05 |

| NCT03041701 (2017-02-02) | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor (IGF-1R) Antibody AMG479 (Ganitumab) in Combination with the Src Family Kinase (SFK) Inhibitor Dasatinib in People with Embryonal and Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma | 2 | Terminated | 2021-10-16 |

| NCT02239861 (2014-09-11) | TAA-Specific CTLS for Solid Tumors (TACTASOM) | 1 | Completed | 2022-04-07 |

| NCT00132158 (2005-08-17) | ZD1839 and Oral Irinotecan in Treating Young Patients with Refractory Solid Tumors | 1 | Completed | 2011-10 |

| NCT02509598 (2015-07-24) | A Study of Lymphoseek® as a Lymphoid Tissue Targeting Agent in Pediatric Patients with Melanoma, Rhabdomyosarcoma, or Other Solid Tumors Who Are Undergoing Lymph Node Mapping | 2 | Completed | 2019-03-06 |

| NCT00075582 (2004-01-09) | Vincristine, Dactinomycin, and Cyclophosphamide with or Without Radiation Therapy in Treating Patients with Newly Diagnosed Low-Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 | Completed | 2021-09-30 |

| NCT01222715 (2010-10-15) | Vinorelbine Tartrate and Cyclophosphamide in Combination with Bevacizumab or Temsirolimus in Treating Patients with Recurrent or Refractory Rhabdomyosarcoma | 2 | Completed | 2015-06 |

| NCT00025363 (2001-10-11) | Comparison of Chemotherapy Regimens in Treating Children with Relapsed or Progressive Rhabdomyosarcoma | 2 | Completed | 2007-10 (primary completion) |

| NCT02372006 (2015-02-24) | Trial of Afatinib in Pediatric Tumours | 1, 2 | Completed | 2020-08-05 |

| NCT00001566 (1999-11-03) | A Pilot Study of Autologous T-Cell Transplantation with Vaccine Driven Expansion of Anti-Tumor Effectors After Cytoreductive Therapy in Metastatic Pediatric Sarcomas | 2 | Completed | 2008-09 |

| NCT00001564 (1999-11-03) | A Pilot Study of Tumor-Specific Peptide Vaccination and IL-2 With or Without Autologous T Cell Transplantation in Recurrent Pediatric Sarcomas | 2 | Completed | 2007-10-25 |

| NCT03441360 (2018-02-15) | Study to Assess Safety and Preliminary Activity of Eribulin Mesylate in Pediatric Participants with Relapsed/Refractory Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), Non-rhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcoma (NRSTS) and Ewing Sarcoma (EWS) | 2 | Completed | 2022-01-21 |

| NCT00001335 (1999-11-03) | New Therapeutic Strategies for Patients with Ewing's Sarcoma Family of Tumors, High Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma, and Neuroblastoma | 2 | Completed | 2002-01 |

| NCT01055314 (2010-01-22) | Temozolomide, Cixutumumab, and Combination Chemotherapy in Treating Patients with Metastatic Rhabdomyosarcoma | 2 | Completed | 2016-06 |

| NCT05093322 (2021-09-20) | A Study of Surufatinib in Combination with Gemcitabine in Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Patients with Recurrent or Refractory Solid Tumors | 1, 2 | Completed | 2023-04-25 |

| NCT04095221 (2019-09-17) | A Study of the Drugs Prexasertib, Irinotecan, and Temozolomide in People with Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumor and Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1, 2 | Completed | 2025-02-18 |

| NCT02581384 (2015-10-19) | Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) for Pulmonary Metastases in Ewing Sarcoma, Rhabdomyosarcoma, and Wilms Tumors | 1, 2 | Terminated | 2020-08 |

| NCT06932861 (2025-04-10) | Exploratory Study of Personalized mRNA Vaccine in Patients with Refractory Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | Not yet recruiting | *2028-05-01 |

| NCT06865664 (2025-03-07) | FGFR4 Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cells in Children and Young Adults with Recurrent or Refractory Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | Not yet recruiting | *2029-04-01 |

| NCT06816771 (2025-02-03) | Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Pazopanib in Combination with TGI/CIV for Recurrent or Refractory Rhabdomyosarcoma in Children or Adolescents | 2 | Recruiting | *2026-12-31 |

| NCT06684327 (2024-11-10) | Multi-cohort, Single-arm Phase II Study of Albumin-paclitaxel, Ifosfamide, and Cisplatin in the Treatment of Rare Advanced Tumors | 2 | Recruiting | *2027-12-30 |

| NCT06456892 (2024-06-07) | Effectiveness of Pucotenlimab Combined with Standard Chemotherapy Regimen | 1, 2 | Recruiting | *2026-12-06 |

| NCT06094101 (2023-09-25) | Personalized Vaccination in Fusion+ Sarcoma Patients (PerVision) | 1, 2 | Recruiting | *2027-09 |

| NCT06023641 (2023-08-27) | Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Rhabdomyosarcoma Using Molecular Risk Stratification and Liposomal Irinotecan Based Therapy in Children with Intermediate and High-Risk Disease | 2 | Recruiting | *2037-10 |

| NCT05304585 (2022-02-24) | Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Very Low-Risk and Low Risk Fusion Negative Rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 | Recruiting | *2030-06-30 |

*: Estimated study completion date

4.1 NRAS and NF1 mutations

The RAS gene encodes a membrane-bound GTPase which cycles between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state. Three members of RAS family NRAS, (Neuroblastoma Rat Sarcoma Virus), HRAS (Harvey Rat Sarcoma Virus) and KRAS (Kirsten Rat sarcoma virus), that transmit signal transduction to regulate a variety of cellular process such as cell growth, differentiation, survival and apoptosis [31-34]. After receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) engagement, guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) such as SOS1, SOS2 and RASGRF are recruited to the plasma membrane to regulate RAS activity through the exchange of GDP for GTP on RAS proteins [35]. Conversely, RAS switches to the inactive form catalyzed by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which in turn accelerates the hydrolysis of bound GTP to GDP [36, 37]. There are two major downstream signaling pathways of RAS including RAF/MEK/ERK (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) cascades [38]. The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway plays a crucial role in cell proliferation, migration and invasion of cancer cells [39, 40]. Active RAS recruits RAF kinase to the plasma membrane, where RAF is activated. Active RAF then phosphorylates and activates MEK which subsequently activate ERK. Active ERK can translocate to the nucleus and activate transcription factors to regulate cell cycle progression [40, 41]. PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling cascade is also the well-studied downstream pathway of RAS which regulates cell progression, protein synthesis, metabolism and cell survival [42]. RAS activates PI3K signaling which phosphorylates phosphoinositides and generates phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), which activates AKT and its substrates, including mTOR, FOXO or NF-κB. The lipid phosphatase PTEN can negatively regulate the PI3K/AKT pathway by dephosphorylating PIP3 and thus reduces the level of phosphorylated AKT. More than 20 percent of cancers contain mutations of RAS family proteins [43], and this accounts for 35% in RMS [27, 44, 45]. Additionally, hypermethylation of the PTEN promoter is found in 90% of FN RMS tumors [46]. Decreased expression level of PTEN or the mutation of PTEN also present in a subset of FN RMS [30, 47, 48]. KRAS mutations are found in approximately 22% of cancers, especially in adenocarcinoma. NRAS mutations present in 8% of tumors with high frequency in melanoma. Only 3% of tumors have HRAS mutations [49, 50]. The RAS mutant defective in GTP hydrolysis can lead to accumulation of GTP-bound RAS and constitutive RAS activation [51] and increase the affinity of NRAS to RAF-1 [52] and PI3K [53].

Gene alterations in FN RMS and FP RMS. The percentage of cases with gene alterations in FN and FP RMS patients were shown. The data used to generate this summary graph were based on results from J.F. Shern et al. [30].

NF1 encodes neurofibromin 1 containing a region which is similar to the catalytic domain of GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) [54]. NF1 stimulates GTPase activity of RAS protein, thereby promoting the formation of inactive RAS-GDP and turning off downstream signaling. Tumors associated with NF1 mutations include glomus tumor [55], optic glioma [56], juvenile xanthogranulomas [57], gastrointestinal stromal tumor [58] and RMS [30]. Inactivating mutations of NF1 results in accumulation of active RAS-GTP leading to constitutive activation of the RAS signaling pathway. Increased active RAS-GTP levels stimulate RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling pathway and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway which ultimately cause increased cell proliferation and inhibit cell apoptosis.

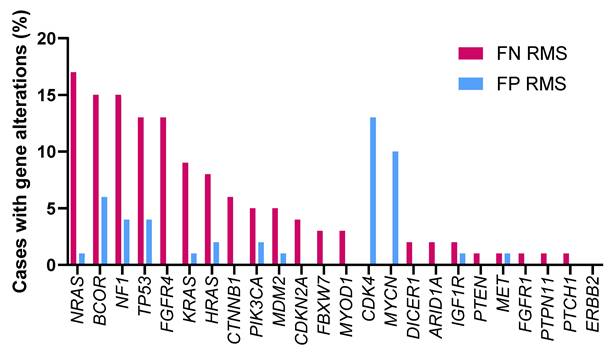

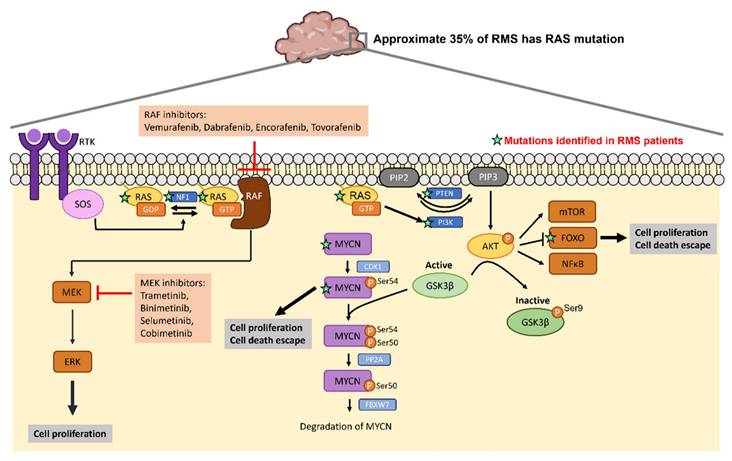

Given the high recurrence in cancers such as colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer and lung cancer, signaling molecules within RAS pathways are potential targets to develop targeted therapeutic strategies. Previous studies have reported small molecules that bind to RAS directly to affect its GTP-GDP regulation [59, 60] or to inhibit the interaction between RAS and GEFs [61, 62]. Table 2 lists the ongoing or completed clinical trials that target downstream effectors of RAS pathway in cancers with RAS mutations. Figure 3 summarizes the mutated genes of FN RMS in RAS pathway and the FDA approved drugs applied to target RAS signaling cascades. The USA FDA has approved four MEK inhibitors for cancer treatment including trametinib, binimetinib, selumetinib and cobimetinib. Several RAF inhibitors have been approved by the USA FDA for treating certain cancers including vemurafenib, dabrafenib, encorafenib and tovorafenib. The confirmed tumor response rate of BRAF mutation-positive, unresectable or metastatic melanoma patients is higher with the treatment of trametinib (22%) compared to chemotherapy (8%). The overall response rate of BRAF mutation-positive, unresectable or metastatic melanoma patients is higher with the treatment of binimetinib plus encorafenib (63%) compared to vemurafenib (40%). The overall response rate of BRAF mutation-positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients is higher with the treatment of dabrafenib plus trametinib (61%) compared to dabrafenib monotherapy (27%). Drugs targeting RAS pathway have been applied to patients with BRAF mutation-positive melanoma, glioma or on-small cell lung cancer. Specifically, RAS mutations have been found in approximate 35% of RMS patients especially in FN RMS [27, 44, 45]. Thus, targeting RAS pathway may have potential for treating RMS.

4.2 CDK4 mutations

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are a family of serine/threonine kinases whose activity depends on a regulatory subunit cyclin and play a crucial role in regulating the cell cycle, apoptosis [63], gene expression [64], and cell differentiation [65]. CDK4 conjugates with cyclin D to drive the transition from G1 to S phase during DNA replication. The CDK4-cyclin D complex and phosphorylates the retinoblastoma (RB) protein which then releases the E2F transcription factor to initiate gene expression for DNA synthesis. CDK-interacting protein/kinase inhibitory protein (CIP/KIP) family and inhibitors of CDK4 (INK4) family are cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. CIP/KIP family members can either inhibit or promote the activity of all major cell cycle CDK/cyclin complexes depending on their posttranslational modification [66]. INK4 family members are able to bind only to CDK4/6-cyclin D complexes and block the progression of the cell cycle [67]. Deregulation of the CDK4/6-cyclin D-INK-RB pathway has been found in a variety of cancers. Hyperactivated CDK4/6 has been reported in many human cancers as a result of overexpression of cyclin D, inactivation of INK4 and CIP/KIP inhibitors or deletion and/or epigenetic alterations of RB [68]. The FDA approved drugs targeting CDK4/6 are listed in Table 3. CDK4/6 inhibitors are commonly used to treat subtypes of breast cancer. Only abemaciclib is used as monotherapy while other drugs are generally used in combinatory therapy. In addition to breast cancer, there are some ongoing and completed clinical trials applying CDK4/6 inhibitors to other cancers (Table 4).

Development of small molecule drugs targeting RAS pathway

| Small molecule drug | Target | Combined agent | Diseases | Phase# | Status | NCT number (Registration Date) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tunlametinib | MEK | PD-1 antibody | Thyroid Cancer | 2 | Not yet recruiting | NCT06970353 (2025-05-06) |

| None | Melanoma | 2 | Completed | NCT05217303 (2022-01-07) | ||

| None | Melanoma | 3 | Recruiting | NCT06008106 (2023-08-08) | ||

| Luvometinib | MEK | None | Melanoma | 1 | Suspended | NCT03932253 (2019-04-25) |

| Trametinib | MEK | CDX-3379 (ERBB3 antibody) | Melanoma | 1, 2 | Terminated | NCT03580382 (2018-07-05) |

| Belvarafenib | RAF | None | Solid Tumor | 1 | Completed | NCT03118817 (2017-03-20) |

| Belvarafenib | RAF | Nivolumab (PD-1 antibody) | Melanoma | 1 | Active, not recruiting | NCT04835805 (2021-04-06) |

| Cobimetinib | MAP2K1 /MEK1 | |||||

| Binimetinib | MEK1/2 | Bocodepsin (HDAC inhibitor) | Melanoma | 1, 2 | Completed | NCT05340621 (2022-02-22) |

| Binimetinib | MEK1/2 | None | Advanced refractory cancers, lymphomas, multiple myeloma | 2 | Active, not recruiting | NCT04439344 (2020-06-18) |

| BDTX-4933 | BRAF | None | Melanoma, histiocytic neoplasms | 1 | Recruiting | NCT05786924 (2023-03-06) |

| Mirdametinib | MEK | None | Multiple myeloma | 1, 2 | Not yet recruiting | NCT06876142 (2025-03-13) |

| Sirolimus | mTOR | |||||

| Onvansertib | PLK1 | FOLFIRI, Bevacizumab | Colorectal cancer | 2 | Completed | NCT05593328 (2022-10-20) |

| FOLFIRI, FOLFOX, Bevacizumab | Colorectal cancer | 2 | Active, not recruiting | NCT06106308 (2023-10-24) | ||

| NST-628 | RAF, MEK | None | Melanoma, solid tumor | 1 | Recruiting | NCT06326411 (2024-03-15) |

| Imalumab | MIF | 5-FU/LV | Colorectal cancer | 2 | Terminated | NCT02448810 (2015-05-15) |

| Exarafenib | RAF | Binimetinib | Solid tumor | 1 | Recruiting | NCT04913285 (2021-05-18) |

| BI 3011441 | MEK | None | Solid Tumor | 1 | Completed | NCT04742556 (2021-02-03) |

| Ulixertinib | ERK1/2 | None | Solid tumor | *Expanded Access | Available | NCT04566393 (2020-09-17) |

*: A way for patients with serious diseases or conditions who cannot participate in a clinical trial to gain access to a medical product that has not been approved by the USA FDA.

Data were collected form https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ accessed on 2025-05-30

RAS mutations in RMS and the corresponding drugs that target RAS signaling cascades. Activation of RTK leads to RAS switch to the active RAS-GTP. RAS-GTP activates RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways leading to increased cell proliferation and cell death escape. FDA approved RAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors can inhibit RAS signaling cascades. The green stars label the mutations identified in RMS patients.

FDA approved drugs targeting CDK4/6

| Drug | Combination drugs/therapy | Common Adverse events | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palbociclib | Endocrine therapy, fulvestrant, aromatase inhibitor, letrozole, PI3K inhibitor + taselisib (NCT02389842), inavolisib (NCT04191499) | Neutropenia, leukopenia, fatigue, thrombocytopenia | USA FDA approved |

| Ribociclib | Fulvestrant, aromatase inhibitor, letrozole, everolimus + exemestane (NCT02732119) | Neutropenia, nausea, thrombocytopenia, QTc prolongation, elevated liver enzymes, creatinine increase | USA FDA approved |

| Abemaciclib | Fulvestrant, nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor | Diarrhea, neutropenia, asymptomatic serum creatinine increase | USA FDA approved |

| Dalpiciclib | Pyrotinib, endocrine therapy, fulvestrant | Neutropenia, leukopenia, diarrhea | China FDA approved |

4.3 BCOR mutations

The BCL6 corepressor (BCOR) was identified as a corepressor interacting with the POZ domain of BCL6. BCOR is a transcription factor which is involved in hematopoiesis, lymphoid development, pluripotency of embryonic stem cells and osteogenic/dentinogenic capacity of mesenchymal stem cells [69, 70]. BCOR can form polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) with RING1, RYBP, NSPC1 and associates with the lysine demethylase 2B (KDM2B) protein to mediate transcriptional repression through epigenetic modifications of histones [71, 72]. It is a tumor suppressor gene and its loss-of-function mutation has been reported in both malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases and is frequently found in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients [73-75]. Mutations of BCOR interrupt assembly of a non-canonical PRC1.1 complex by unlinking the enzymatic core from the chromatin-targeting complex. As a result, BCOR-mutated PRC1.1 can localize to chromatin without repressive activity, resulting in epigenetic reprogramming and aberrant transcriptional activation of oncogenic signaling programs [72]. Patients with BCOR mutation have a reduced survival rate and poor prognosis since BCOR mutations have been linked to resistance to certain chemotherapy drugs [74, 76]. While there aren't currently any drugs specifically targeting BCOR mutations, researchers are exploring targeted therapies based on the mechanisms through which BCOR mutations drive cancer development. Approximately 65% of uterine sarcoma patients with BCOR-rearranged mutations have CDK4 amplification or CDKN2A gene inactivation and multiple genes in the CDK4 pathway are overexpressed in BCOR-CCNB3-fused sarcomas [77, 78], suggesting potential targeted therapeutic implications of CDK4/6 inhibitors in BCOR mutated patients.

Ongoing and completed clinical trials applying CDK4/6 inhibitors to cancers except for breast cancer

| Type of cancer | Drugs/therapies | Phase# | Status | NCT number (Registration Date) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chordoma | Palbociclib | 2 | Completed | NCT03110744 (2017-03-31) |

| Medulloblastoma | Palbociclib, Ribociclib, Abemaciclib | Early 1 | Recruiting | NCT06959979 (2024-07-24) |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | Trilaciclib | 2 | Recruiting | NCT06328049 (2024-03-13) |

| Osimertinib + Dalpiciclib | 2 | Recruiting | NCT06363734 (2024-04-09) | |

| Ribociclib + Ceritinib | 1 | Completed | NCT02292550 (2014-11-12) | |

| Small cell lung cancer | Abemaciclib | 2 | Recruiting | NCT04010357 (2019-07-03) |

| Trilaciclib + Topotecan | 4 | Recruiting | NCT05874401 (2023-04-12) | |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Dalpiciclib + Camrelizumab | 2 | Unknown status | NCT05724355 (2023-02-02) |

| Meningioma | Abemaciclib | 2 | Recruiting | NCT05940493 (2023-07-04) |

| Liposarcoma | Palbociclib + INCMGA00012 | 2 | Active, not recruiting | NCT04438824 (2020-06-17) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | TCK-276 | 1 | Completed | NCT05437419 (2022-06-23) |

| Ovarian Carcinoma | Dalpiciclib + Letrozole | 2 | Recruiting | NCT06243185 (2024-01-09) |

| Abemaciclib | 2 | Recruiting | NCT04469764 (2020-07-06) | |

| Glioblastoma | Abemaciclib + Bevacizumab | Early 1 | Active, not recruiting | NCT04074785 (2019-08-28) |

| Prostate cancer | Abemaciclib | 2 | Completed | NCT01739309 (2012-11-29) |

| Docetaxel + Ribociclib | 1, 2 | Completed | NCT02494921 (2015-07-08) | |

| Palbociclib | 2 | Active, not recruiting | NCT02905318 (2016-09-08) | |

| Abemaciclib | 2 | Completed | NCT04408924 (2020-05-28) | |

| Solid tumor (except breast cancer (however, triple negative was included), liposarcoma, CRPC, melanoma and teratoma) or hematological malignancy (except mantle cell lymphoma) | Ribociclib | 2 | Completed | NCT02187783 (2014-07-09) |

Data were collected form https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ accessed on 2025-05-30

4.4 MYCN mutations

The MYCN gene is a member of the MYC oncogene family, which consists of MYCC, MYCN and MYCL. The MYC family plays a crucial role in governing the gene expression related to cell proliferation, differentiation, protein synthesis, metabolism and apoptosis [79-81]. MYCN gene encodes a transcription factor N-MYC with a short half-life around 30 min [82] whose stability is related to phosphorylation on specific residues. First, CDK1-cyclin B1 phosphorylates N-MYC at Ser54. Then serine-threonine kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) recognizes N-MYC (pSer54) and phosphorylates it at Thr50 subsequently triggering protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A)-dependent dephosphorylation of Ser54. Next, F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7 (FBXW7) polyubiquitinates N-MYC leading to proteasomal degradation [83-85]. When the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated, active phospho-AKT phosphorylates and inactivates GSK3β resulting in stabilization of N-MYC [86, 87]. The deregulation of MYCN occurs in many kinds of cancers and is related to poor prognosis. Amplification of MYCN has been observed in 17-22% of all neuroblastomas [88, 89] and 5-50% of medulloblastomas [90-92]. Approximately 25% of aRMS cases have amplification of MYCN and 55% of aRMS cases have overexpression of MYCN [93, 94]. Previous studies also showed amplification or overexpression of MYCN in neuroendocrine prostate cancers, prostate adenocarcinomas, small-cell lung cancers and breast cancer [95-98]. These findings of aberrant expression of MYCN in a variety of cancers suggest N-MYC as a therapeutic target.

5. Conclusion and future perspectives

Cancer biomarkers are useful for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response. Biomarker testing is an important part of precision medicine such as targeted therapy to tailor treatment plans to an individual patient. The field of targeted therapy in cancer management is rapidly evolving because of new discovery of molecular targets, development of new targeted drugs and exploration of different combination strategies.

RMS is a rare cancer that can start in any soft tissues. The diagnosis is performed by conducting physical exams and scans such as MRI, CT or a bone scan. The first line therapy of RMS involves conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy that affects all rapidly dividing cells. Developing targeted therapies and immunotherapies would be more specific to RMS and lead to less side effects. Once RMS being diagnosed, genetic testing of PAX-FOXO1 fusion gene would be conducted. The constitutively nuclear-localized PAX-FOXO1 fusion protein drives tumorigenesis and is associated with poor prognosis in FP aRMS by modulating the transcription of several genes such as FGFR4, IGF2 and CXCR4. While PAX-FOXO1 fusion gene was observed in 16% of all RMS cases, identifying other gene mutations with a high frequency of occurrence would provide a more comprehensive and efficient therapeutic approach. This review summarizes the potential biomarkers in RMS. A high frequency (15%) of mutations in NRAS, BCOR and NF1 genes were observed in FN RMS while mutations in CDK4 and MYCN are more common in FP RMS. There are several developing drugs and clinical trials targeting to these mutations. If the specific genetic mutation can be detected during early diagnosis, targeted therapy would provide more appropriate and effective personalized treatment for RMS patients.

In addition to targeted therapy, studies also reveal the potential application of immunotherapy in RMS. Specific antigens of RMS were identified as immune markers [99-101]. Lavoie RR et al. reported the novel mechanistic insights on the role of B7-H3 in tumor immune evasion and RMS progression [99]. Cell-based immunotherapy using EGFR-CAR NK cell confers high efficiency against chemotherapy-resistant RMS cells [102]. Nonetheless, cancers treated with a single-agent therapy would eventually acquire resistance leading to reduced sensitivity during subsequent treatment lines. The combination of targeted therapy and immunotherapy in RMS may overcome drug resistance and improve the outcomes for patients while reducing the side-effects and providing a long-lasting defense against relapses.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (grant # NSTC 113-2320-B-007-006-MY3) and from the National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan (grant # 114QF001E1).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: L.C. and T.-L.K. Writing and editing: L.C. and T.-L.K. Visualization: T.-L.K. All authors contributed to the article approved the submitted version.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Adewuyi E, Chorya H, Muili A, Moradeyo A, Kayode A, Naik A. et al. Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy for osteosarcoma: Recent advancements. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2025;206:104575

2. Hu Z, Wen S, Huo Z, Wang Q, Zhao J, Wang Z. et al. Current Status and Prospects of Targeted Therapy for Osteosarcoma. Cells. 2022 11

3. Martin-Giacalone BA, Weinstein PA, Plon SE, Lupo PJ. Pediatric Rhabdomyosarcoma: Epidemiology and Genetic Susceptibility. J Clin Med. 2021 10

4. Pappo AS, Anderson JR, Crist WM, Wharam MD, Breitfeld PP, Hawkins D. et al. Survival after relapse in children and adolescents with rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3487-93

5. Pappo AS, Lyden E, Breitfeld P, Donaldson SS, Wiener E, Parham D. et al. Two consecutive phase II window trials of irinotecan alone or in combination with vincristine for the treatment of metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:362-9

6. Skapek SX, Ferrari A, Gupta AA, Lupo PJ, Butler E, Shipley J. et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:1

7. Hawkins WG, Hoos A, Antonescu CR, Urist MJ, Leung DH, Gold JS. et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of patients with adult rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2001;91:794-803

8. Sultan I, Qaddoumi I, Yaser S, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Ferrari A. Comparing adult and pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1973 to 2005: an analysis of 2,600 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3391-7

9. Board WCoTE. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours WHO Classification of Tumours, 5th Edition, Volume 3: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020; 2020

10. Parham DM, Ellison DA. Rhabdomyosarcomas in adults and children: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1454-65

11. Shern JF, Chen L, Chmielecki J, Wei JS, Patidar R, Rosenberg M. et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of rhabdomyosarcoma reveals a landscape of alterations affecting a common genetic axis in fusion-positive and fusion-negative tumors. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:216-31

12. Barr FG, Smith LM, Lynch JC, Strzelecki D, Parham DM, Qualman SJ. et al. Examination of gene fusion status in archival samples of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma entered on the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-III trial: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:202-8

13. Dumont SN, Lazar AJ, Bridge JA, Benjamin RS, Trent JC. PAX3/7-FOXO1 fusion status in older rhabdomyosarcoma patient population by fluorescent in situ hybridization. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:213-20

14. Ahn EH. Regulation of target genes of PAX3-FOXO1 in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2029-35

15. Loupe JM, Miller PJ, Bonner BP, Maggi EC, Vijayaraghavan J, Crabtree JS. et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals the oncogenic fusion protein PAX3-FOXO1 globally alters mRNA and miRNA to enhance myoblast invasion. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e246

16. Khan J, Wei JS, Ringner M, Saal LH, Ladanyi M, Westermann F. et al. Classification and diagnostic prediction of cancers using gene expression profiling and artificial neural networks. Nat Med. 2001;7:673-9

17. Ayalon D, Glaser T, Werner H. Transcriptional regulation of IGF-I receptor gene expression by the PAX3-FKHR oncoprotein. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2001;11:289-97

18. Tomescu O, Xia SJ, Strezlecki D, Bennicelli JL, Ginsberg J, Pawel B. et al. Inducible short-term and stable long-term cell culture systems reveal that the PAX3-FKHR fusion oncoprotein regulates CXCR4, PAX3, and PAX7 expression. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1060-70

19. Khan J, Bittner ML, Saal LH, Teichmann U, Azorsa DO, Gooden GC. et al. cDNA microarrays detect activation of a myogenic transcription program by the PAX3-FKHR fusion oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13264-9

20. Davicioni E, Finckenstein FG, Shahbazian V, Buckley JD, Triche TJ, Anderson MJ. Identification of a PAX-FKHR gene expression signature that defines molecular classes and determines the prognosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6936-46

21. Donaldson SS, Meza J, Breneman JC, Crist WM, Laurie F, Qualman SJ. et al. Results from the IRS-IV randomized trial of hyperfractionated radiotherapy in children with rhabdomyosarcoma-a report from the IRSG. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:718-28

22. Little DJ, Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Pisters PW, Patel SR, El-Naggar AK. et al. Adult rhabdomyosarcoma: outcome following multimodality treatment. Cancer. 2002;95:377-88

23. Stevens MC, Rey A, Bouvet N, Ellershaw C, Flamant F, Habrand JL. et al. Treatment of nonmetastatic rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood and adolescence: third study of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology-SIOP Malignant Mesenchymal Tumor 89. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2618-28

24. Pappo AS, Shapiro DN, Crist WM, Maurer HM. Biology and therapy of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2123-39

25. Crist WM, Anderson JR, Meza JL, Fryer C, Raney RB, Ruymann FB. et al. Intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study-IV: results for patients with nonmetastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3091-102

26. Shukla N, Ameur N, Yilmaz I, Nafa K, Lau CY, Marchetti A. et al. Oncogene mutation profiling of pediatric solid tumors reveals significant subsets of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and neuroblastoma with mutated genes in growth signaling pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:748-57

27. Stratton MR, Fisher C, Gusterson BA, Cooper CS. Detection of point mutations in N-ras and K-ras genes of human embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas using oligonucleotide probes and the polymerase chain reaction. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6324-7

28. Taylor AC, Shu L, Danks MK, Poquette CA, Shetty S, Thayer MJ. et al. P53 mutation and MDM2 amplification frequency in pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma tumors and cell lines. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35:96-103

29. Taylor JGt, Cheuk AT, Tsang PS, Chung JY, Song YK, Desai K. et al. Identification of FGFR4-activating mutations in human rhabdomyosarcomas that promote metastasis in xenotransplanted models. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3395-407

30. Shern JF, Selfe J, Izquierdo E, Patidar R, Chou HC, Song YK. et al. Genomic Classification and Clinical Outcome in Rhabdomyosarcoma: A Report From an International Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2859-71

31. Cox AD, Der CJ. The dark side of Ras: regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2003;22:8999-9006

32. Eisfeld AK, Schwind S, Hoag KW, Walker CJ, Liyanarachchi S, Patel R. et al. NRAS isoforms differentially affect downstream pathways, cell growth, and cell transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:4179-84

33. McCormick F. Ras-related proteins in signal transduction and growth control. Mol Reprod Dev. 1995;42:500-6

34. Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 in cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene. 2001;20:2390-400

35. Buday L, Downward J. Epidermal growth factor regulates p21ras through the formation of a complex of receptor, Grb2 adapter protein, and Sos nucleotide exchange factor. Cell. 1993;73:611-20

36. Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell. 2007;129:865-77

37. Lowy DR, Willumsen BM. Function and regulation of ras. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:851-91

38. De Luca A, Maiello MR, D'Alessio A, Pergameno M, Normanno N. The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and the PI3K/AKT signalling pathways: role in cancer pathogenesis and implications for therapeutic approaches. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(Suppl 2):S17-27

39. Lavoie H, Gagnon J, Therrien M. ERK signalling: a master regulator of cell behaviour, life and fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:607-32

40. Samson SC, Khan AM, Mendoza MC. ERK signaling for cell migration and invasion. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:998475

41. Mendoza MC, Er EE, Blenis J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways: cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:320-8

42. Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT. The PI3K Pathway in Human Disease. Cell. 2017;170:605-35

43. Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:459-65

44. Schaaf G, Hamdi M, Zwijnenburg D, Lakeman A, Geerts D, Versteeg R. et al. Silencing of SPRY1 triggers complete regression of rhabdomyosarcoma tumors carrying a mutated RAS gene. Cancer Res. 2010;70:762-71

45. Nakagawa N, Kikuchi K, Yagyu S, Miyachi M, Iehara T, Tajiri T. et al. Mutations in the RAS pathway as potential precision medicine targets in treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;512:524-30

46. Seki M, Nishimura R, Yoshida K, Shimamura T, Shiraishi Y, Sato Y. et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis defines novel molecular subgroups in rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7557

47. Zhu B, Zhang M, Williams EM, Keller C, Mansoor A, Davie JK. TBX2 represses PTEN in rhabdomyosarcoma and skeletal muscle. Oncogene. 2016;35:4212-24

48. Lian YL, Chen KW, Chou YT, Ke TL, Chen BC, Lin YC. et al. PIP3 depletion rescues myoblast fusion defects in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. J Cell Sci. 2020 133

49. Hobbs GA, Der CJ, Rossman KL. RAS isoforms and mutations in cancer at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:1287-92

50. Prior IA, Lewis PD, Mattos C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2457-67

51. Herrmann C. Ras-effector interactions: after one decade. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:122-9

52. Moodie SA, Willumsen BM, Weber MJ, Wolfman A. Complexes of Ras.GTP with Raf-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. Science. 1993;260:1658-61

53. Sjolander A, Yamamoto K, Huber BE, Lapetina EG. Association of p21ras with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:7908-12

54. Xu GF, O'Connell P, Viskochil D, Cawthon R, Robertson M, Culver M. et al. The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene encodes a protein related to GAP. Cell. 1990;62:599-608

55. Kumar MG, Emnett RJ, Bayliss SJ, Gutmann DH. Glomus tumors in individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:44-8

56. Tang Y, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Optic Pathway Gliomas: Current Challenges and Future Prospects. Cancer Manag Res. 2023;15:667-81

57. Liy-Wong C, Mohammed J, Carleton A, Pope E, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. The relationship between neurofibromatosis type 1, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and malignancy: A retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1084-7

58. Zhang W, Hu X, Chen Z, Lai C. Case report: Neurofibromatosis type 1 gastrointestinal stromal tumor and small bowel adenocarcinoma with a novel germline NF1 frameshift mutation. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1052799

59. Hunter JC, Gurbani D, Ficarro SB, Carrasco MA, Lim SM, Choi HG. et al. In situ selectivity profiling and crystal structure of SML-8-73-1, an active site inhibitor of oncogenic K-Ras G12C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8895-900

60. Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013;503:548-51

61. Maurer T, Garrenton LS, Oh A, Pitts K, Anderson DJ, Skelton NJ. et al. Small-molecule ligands bind to a distinct pocket in Ras and inhibit SOS-mediated nucleotide exchange activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5299-304

62. Sun Q, Burke JP, Phan J, Burns MC, Olejniczak ET, Waterson AG. et al. Discovery of small molecules that bind to K-Ras and inhibit Sos-mediated activation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:6140-3

63. Golsteyn RM. Cdk1 and Cdk2 complexes (cyclin dependent kinases) in apoptosis: a role beyond the cell cycle. Cancer Lett. 2005;217:129-38

64. Fisher RP. CDK regulation of transcription by RNAP II: Not over 'til it's over? Transcription. 2017;8:81-90

65. Hydbring P, Malumbres M, Sicinski P. Non-canonical functions of cell cycle cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:280-92

66. Csergeova L, Krbusek D, Janostiak R. CIP/KIP and INK4 families as hostages of oncogenic signaling. Cell Div. 2024;19:11

67. Canepa ET, Scassa ME, Ceruti JM, Marazita MC, Carcagno AL, Sirkin PF. et al. INK4 proteins, a family of mammalian CDK inhibitors with novel biological functions. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:419-26

68. Deshpande A, Sicinski P, Hinds PW. Cyclins and cdks in development and cancer: a perspective. Oncogene. 2005;24:2909-15

69. Fan Z, Yamaza T, Lee JS, Yu J, Wang S, Fan G. et al. BCOR regulates mesenchymal stem cell function by epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1002-9

70. Kelly MJ, So J, Rogers AJ, Gregory G, Li J, Zethoven M. et al. Bcor loss perturbs myeloid differentiation and promotes leukaemogenesis. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1347

71. Gearhart MD, Corcoran CM, Wamstad JA, Bardwell VJ. Polycomb group and SCF ubiquitin ligases are found in a novel BCOR complex that is recruited to BCL6 targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6880-9

72. Schaefer EJ, Wang HC, Karp HQ, Meyer CA, Cejas P, Gearhart MD. et al. BCOR and BCORL1 Mutations Drive Epigenetic Reprogramming and Oncogenic Signaling by Unlinking PRC1.1 from Target Genes. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022;3:116-35

73. Grossmann V, Tiacci E, Holmes AB, Kohlmann A, Martelli MP, Kern W. et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of BCOR in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype. Blood. 2011;118:6153-63

74. Honda A, Koya J, Yoshimi A, Miyauchi M, Taoka K, Kataoka K. et al. Loss-of-function mutations in BCOR contribute to chemotherapy resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2021;101-102:42-8 e11

75. Kang JH, Lee SH, Lee J, Choi M, Cho J, Kim SJ. et al. The mutation of BCOR is highly recurrent and oncogenic in mature T-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:82

76. Hu D, Shen K, Guo Y, Bao XB, Dong N, Chen S. The clinical implications of BCOR mutations in a large cohort of acute myeloid leukemia patients: a 5-year single-center retrospective study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2024;65:1964-73

77. Lin DI, Hemmerich A, Edgerly C, Duncan D, Severson EA, Huang RSP. et al. Genomic profiling of BCOR-rearranged uterine sarcomas reveals novel gene fusion partners, frequent CDK4 amplification and CDKN2A loss. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;157:357-66

78. Tramontana TF, Marshall MS, Helvie AE, Schmitt MR, Ivanovich J, Carter JL. et al. Sustained Complete Response to Palbociclib in a Refractory Pediatric Sarcoma With BCOR-CCNB3 Fusion and Germline CDKN2B Variant. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020 4

79. Bretones G, Delgado MD, Leon J. Myc and cell cycle control. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1849:506-16

80. Conacci-Sorrell M, Eisenman RN. Post-translational control of Myc function during differentiation. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:604-10

81. McMahon SB. MYC and the control of apoptosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a014407

82. Cohn SL, Salwen H, Quasney MW, Ikegaki N, Cowan JM, Herst CV. et al. Prolonged N-myc protein half-life in a neuroblastoma cell line lacking N-myc amplification. Oncogene. 1990;5:1821-7

83. Bonvini P, Nguyen P, Trepel J, Neckers LM. In vivo degradation of N-myc in neuroblastoma cells is mediated by the 26S proteasome. Oncogene. 1998;16:1131-9

84. Otto T, Horn S, Brockmann M, Eilers U, Schuttrumpf L, Popov N. et al. Stabilization of N-Myc is a critical function of Aurora A in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:67-78

85. Sjostrom SK, Finn G, Hahn WC, Rowitch DH, Kenney AM. The Cdk1 complex plays a prime role in regulating N-myc phosphorylation and turnover in neural precursors. Dev Cell. 2005;9:327-38

86. Chesler L, Schlieve C, Goldenberg DD, Kenney A, Kim G, McMillan A. et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase destabilizes Mycn protein and blocks malignant progression in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8139-46

87. Kenney AM, Widlund HR, Rowitch DH. Hedgehog and PI-3 kinase signaling converge on Nmyc1 to promote cell cycle progression in cerebellar neuronal precursors. Development. 2004;131:217-28

88. Brodeur GM. Neuroblastoma: biological insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:203-16

89. Campbell K, Naranjo A, Hibbitts E, Gastier-Foster JM, Bagatell R, Irwin MS. et al. Association of heterogeneous MYCN amplification with clinical features, biological characteristics and outcomes in neuroblastoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Eur J Cancer. 2020;133:112-9

90. Aldosari N, Bigner SH, Burger PC, Becker L, Kepner JL, Friedman HS. et al. MYCC and MYCN oncogene amplification in medulloblastoma. A fluorescence in situ hybridization study on paraffin sections from the Children's Oncology Group. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:540-4

91. Behdad A, Perry A. Central nervous system primitive neuroectodermal tumors: a clinicopathologic and genetic study of 33 cases. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:441-50

92. Gessi M, von Bueren A, Treszl A, zur Muhlen A, Hartmann W, Warmuth-Metz M. et al. MYCN amplification predicts poor outcome for patients with supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:924-32

93. Tonelli R, McIntyre A, Camerin C, Walters ZS, Di Leo K, Selfe J. et al. Antitumor activity of sustained N-myc reduction in rhabdomyosarcomas and transcriptional block by antigene therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:796-807

94. Williamson D, Lu YJ, Gordon T, Sciot R, Kelsey A, Fisher C. et al. Relationship between MYCN copy number and expression in rhabdomyosarcomas and correlation with adverse prognosis in the alveolar subtype. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:880-8

95. Beltran H, Rickman DS, Park K, Chae SS, Sboner A, MacDonald TY. et al. Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:487-95

96. Nau MM, Brooks BJ Jr, Carney DN, Gazdar AF, Battey JF, Sausville EA. et al. Human small-cell lung cancers show amplification and expression of the N-myc gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:1092-6

97. Funa K, Steinholtz L, Nou E, Bergh J. Increased expression of N-myc in human small cell lung cancer biopsies predicts lack of response to chemotherapy and poor prognosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;88:216-20

98. Mizukami Y, Nonomura A, Takizawa T, Noguchi M, Michigishi T, Nakamura S. et al. N-myc protein expression in human breast carcinoma: prognostic implications. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:2899-905

99. Lavoie RR, Gargollo PC, Ahmed ME, Kim Y, Baer E, Phelps DA. et al. Surfaceome Profiling of Rhabdomyosarcoma Reveals B7-H3 as a Mediator of Immune Evasion. Cancers (Basel). 2021 13

100. Timpanaro A, Piccand C, Uldry AC, Bode PK, Dzhumashev D, Sala R. et al. Surfaceome Profiling of Cell Lines and Patient-Derived Xenografts Confirm FGFR4, NCAM1, CD276, and Highlight AGRL2, JAM3, and L1CAM as Surface Targets for Rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 24

101. Orentas RJ, Yang JJ, Wen X, Wei JS, Mackall CL, Khan J. Identification of cell surface proteins as potential immunotherapy targets in 12 pediatric cancers. Front Oncol. 2012;2:194

102. Reindl LM, Jalili L, Bexte T, Harenkamp S, Thul S, Hehlgans S. et al. Precision targeting of rhabdomyosarcoma by combining primary CAR NK cells and radiotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2025 13

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Linyi Chen, Ph.D. Department of Medical Science and Institute of Molecular Medicine, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan. E-mail: lchennthu.edu.tw; linyiccom; Tel: 886-3-5742775.

Corresponding author: Linyi Chen, Ph.D. Department of Medical Science and Institute of Molecular Medicine, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan. E-mail: lchennthu.edu.tw; linyiccom; Tel: 886-3-5742775.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact