Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2026; 17(1):142-156. doi:10.7150/jca.125763 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Comprehensive characterization of AP-1 adaptor complex genes in lung cancer reveals AP1AR as a novel prognostic and therapeutic biomarker

1. Graduate Institute of Cancer Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

2. Yogananda School of AI Computers and Data Sciences, Shoolini University, Solan 173229, India.

3. Department of Emergency Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung 80708, Taiwan.

4. Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung 80708, Taiwan.

5. Medical Laboratory, Medical Education and Research Center, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, Kaohsiung 80284, Taiwan.

6. Division of Experimental Surgery Center, Department of Surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical University, Taipei, 11490, Taiwan.

7. Institute of Medical Science and Technology, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung, 80424, Taiwan.

8. Department of Medical Imaging, Chi-Mei Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan.

9. Department of Health and Nutrition, Chia Nan University of Pharmacy and Science, Tainan, Taiwan.

10. School of Medicine, College of Medicine, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

11. Nursing Department, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, Kaohsiung 80284, Taiwan.

12. Ph.D. Program for Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

13. Faculty of Applied Sciences and Biotechnology, Shoolini University of Biotechnology and Management Sciences, Himachal Pradesh, India.

14. Faculty of Pharmacy, Van Lang University, 69/68 Dang Thuy Tram Street, Binh Loi Trung Ward, Ho Chi Minh City, 70000, Vietnam.

15. Department of Biotechnology, Mother Teresa Women's University, Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu, 624101, India.

16. Computer Engineering with specialization in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, Presidency University, Yelahanka, Bengaluru 560064 India.

17. TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

18. Traditional Herbal Medicine Research Center of Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

19. Cancer Center, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

20. Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Rensselaer, NY 12144, USA.

# Equal contributors.

Received 2025-9-24; Accepted 2025-11-13; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer mortality. The AP-1 adaptor complex, including AP1AR, AP1S1, AP1S2, AP1S3, AP1M1, AP1M2, AP1B1, and AP1G1, functions as a conserved hub of vesicular trafficking, selecting cargo and coordinating clathrin-mediated transport. By shaping receptor recycling, membrane composition, and signal duration, AP-1 influences core cancer phenotypes such as proliferation, migration, and therapy response. However, the family-level role of AP-1 adaptors in lung cancer is incompletely defined. We systematically profiled all eight AP-1 adaptor genes using multi-omics datasets, survival resources, pharmacogenomic panels, Human Protein Atlas data, pathway enrichment, and single-cell RNA sequencing with cell-cell communication modeling. AP1AR was consistently upregulated in lung adenocarcinoma and independently associated with poorer overall survival. It was linked to cell-cycle progression, DNA replication checkpoints, hypoxia, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). At single cell resolution, AP1AR also regulate malignant epithelial and fibroblast cell types. Pseudotime analyses revealed progressive activation along proliferative and EMT axes, and CellChat modeling indicated enhanced stromal and epithelial signaling. AP1S3 and AP1S1 showed complementary roles, associated with oncogenic/inflammatory signaling and immune-metabolic programs, respectively. These findings identify AP1AR as a clinically relevant biomarker and highlight AP-1 adaptor biology as an underexplored contributor to lung adenocarcinoma progression and therapeutic stratification.

Keywords: AP-1 adaptor complex, AP1AR, lung cancer, biomarker, multi-omics analysis, single-cell RNA sequencing, prognosis and therapeutic target

1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with survival rates remaining poor despite advances in molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapy [1, 2]. Identifying novel molecular regulators of tumor progression is therefore essential for discovering new biomarkers and therapeutic targets [3-5]. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of cases and is primarily divided into two major histological subtypes: lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC). Adaptor protein (AP) complexes are evolutionarily conserved regulators of intracellular trafficking that mediate cargo sorting among endosomes, lysosomes, and the trans-Golgi network [6]. Among them, the AP-1 adaptor complex plays a central role in clathrin-mediated transport, linking membrane dynamics to cell signaling and homeostasis [7]. Dysregulation of AP complexes has been implicated in several cancers, where altered vesicle trafficking can affect oncogenic receptor turnover, nutrient signaling, and immune evasion [8-10]. While several AP-1 adaptor subunits, such as AP1B1 and AP1G1, have been studied in cancer [11, 12], a systematic evaluation of the AP-1 adaptor family in lung cancer is lacking. Notably, AP1AR (adaptor protein complex 1-associated regulatory) has not been characterized in lung cancer or other solid tumors, representing an opportunity to explore novel mechanisms of tumor regulation.

Recent multi-omics resources enable comprehensive evaluation of gene families across diverse cancer datasets [13-17]. Integrative analyses combining bulk transcriptomics, clinical outcomes, protein expression, drug-sensitivity correlations, pathway enrichment, and single-cell data allow robust characterization of candidate genes [18-20]. Using this approach, we present the first systematic analysis of eight AP-1 adaptor genes in lung cancer. We show that AP1AR is consistently upregulated, associated with poor survival, enriched for cell-cycle and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathways, and localized to malignant epithelial and fibroblast cell types at the single-cell level. AP1S3 and AP1S1 provide complementary support, while other family members offer broader context. These findings establish AP1AR as a novel prognostic biomarker and potential therapeutic target and highlight the AP-1 adaptor complex as an underexplored contributor to lung cancer biology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 RNA-seq Expression and Clinical Data

Transcriptomic expression data and corresponding clinical annotations for LUAD and normal lung tissues were obtained from UALCAN, which compiles The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Level 3 RNA-seq (HTSeq-FPKM) datasets [21, 22]. Analyses included tumor versus regular comparisons, pathological stage-specific profiling, and pan-cancer assessments. Expression values were log2-transformed as transcripts per million (TPM + 1) to ensure comparability across datasets. Prognostic associations were evaluated using three independent platforms to enhance reproducibility [23-25]. SurvivalGenie v2.0 was used to generate volcano plots and multivariate Cox regression-based forest plots across TCGA cohorts [26]. GEPIA2 provided Kaplan-Meier survival curves and hazard ratios, while KMplotter was employed to validate associations in independent LUAD samples [27, 28]. Patients were stratified into high- and low-expression groups based on the median value unless otherwise indicated [29-31]. Statistical significance was determined using log-rank p values, with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) reported.

2.2 DNA-Methylation and Protein Expression Profiling

DNA-methylation data for AP1AR and AP1S3 were obtained from the TCGA-LUAD and TCGA-LUSC cohorts via the UCSC Xena browser, and promoter-level β-values were analyzed [32]. Methylation profiles were visualized using heatmaps and boxplots to compare tumor and adjacent normal tissues. Functional dependency data from DepMap (23Q4 release) were used to assess the essentiality of AP1AR and AP1S3 across lung cancer cell lines [33]. Protein expression and subcellular localization were evaluated using immunohistochemistry (IHC) data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) [34]. Representative staining images for normal and tumor lung tissues were examined, and staining intensity was classified as not detected, low, medium, or high. Localization patterns were compared between tumor and normal specimens to validate transcriptomic observations at the protein level [35-37].

2.3 Drug-Sensitivity and Gene Set Enrichment and Pathway Analyses

Drug response correlations were analyzed through the Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA) platform [38], supplemented with data from the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) [39] and the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) [40]. Gene expression levels were correlated with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients. Associations with false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant [41-43]. Functional enrichment analyses were performed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) and MetaCore (Clarivate Analytics). GSEA was conducted utilizing the fgsea R package (Bioconductor v3.19) [44], which employs hallmark and curated gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB v7.5.1) [45]. Analyses were based on 10,000 permutations, and pathways with normalized enrichment scores (NESs) and an FDR of < 0.05 were considered significant. MetaCore was used to validate enrichment results and identify curated pathways relevant to cancer progression [46-48]. Additionally, protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks among the eight AP-1 adaptor genes were generated using STRING v12.0, with a medium-confidence threshold set to 0.4 to identify functionally relevant interactions [49].

2.4 Single-Cell Transcriptomic and Cell-Cell Communication Analysis

Single-cell RNA-seq data were analyzed using the GSE202159 dataset [50], accessed via the cellxgene platform [51]. Processed data, including quality-controlled cell clusters and annotated major lineages (epithelial, fibroblast, endothelial, myeloid, lymphoid, and T/natural killer (NK) cells), were used for downstream analyses. Gene expression patterns of the AP-1 adaptor genes were visualized using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) dimensionality-reduction techniques. Expression intensities were displayed on feature plots, and relative enrichment was assessed across clusters via heatmaps [52-54]. Cell-cycle states (G1, S, and G2/M) were inferred using canonical phase markers. Pseudotime trajectories were reconstructed using the Slingshot algorithm within the SingleCellPipeline (SCP) package to infer lineage relationships and temporal expression trends for AP1AR and AP1S3. Correlation analyses were performed against DNA-repair gene sets (BRCA1, RAD51, ATM and PARP1). Clinical metadata, including tumor stage, histological subtype, and smoking status, were integrated for contextual interpretation and analysis [55-58]. Clinical metadata, including tumor stage, histological subtype, and smoking status, were incorporated to contextualize expression patterns within tumor progression. To evaluate intercellular signaling networks associated with target gene expressions, CellChat [59] was applied to the GSE202159 object. Separate analyses were performed for high- and low-expression cell subsets. The inferred signaling probabilities were visualized as global communication networks, lineage-specific connectivity heatmaps, and directional sender-receiver maps [60-64].

2.5 Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using publicly available platforms and locally installed software [65-67]. Data handling and visualization used R/RStudio with the ggplot2 package [68-70], SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) [71]. Additional exploratory analyses were conducted with Omics Playground v3.4.1[72] and SRPlot [73-75]. Quantitative data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent experiments [73-75]. Group differences were assessed using one-way or two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons [76, 77]. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test [78-80]. HRs with corresponding 95% CIs were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models when appropriate. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical tests were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 Expression and Prognostic Relevance Extents of AP-1 Adaptor Genes in Lung Cancer

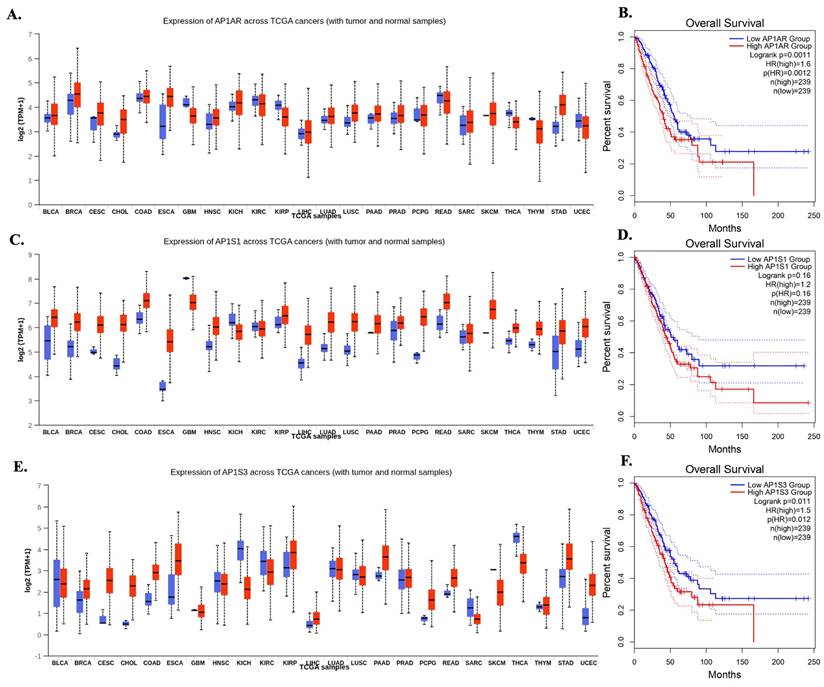

A systematic multi-omics analysis was conducted for the eight AP-1 adaptor complex genes (AP1AR, AP1B1, AP1G1, AP1G2, AP1M1, AP1M2, AP1S1, and AP1S3) to characterize their roles in lung cancer. These genes were investigated by integrating bulk RNA-seq, clinical outcomes, protein expression, drug-sensitivity correlations, pathway enrichment, and single-cell transcriptomics. To identify key candidates, gene expression patterns and associations with patient survival were first evaluated across TCGA datasets using the UALCAN platform. Among the eight genes, AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 were consistently upregulated in LUAD relative to normal lung tissues (Figure 1A, C, E), whereas other family members showed variable or minimal changes (Supplementary Figure S1). Kaplan-Meier analyses indicated that high expression of AP1AR and AP1S3 correlated with shorter overall survival (OS), with AP1S1 showing a weaker but similar trend (Figure 1B, D, F). Multivariate Cox regression using SurvivalGenie confirmed AP1AR and AP1S3 as independent adverse prognostic markers (HRs > 1, p < 0.05), while AP1S1 did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2A). Pathological stage-specific analyses revealed progressive upregulation of AP1AR and AP1S3 with advancing tumor stage, whereas AP1S1 expression remained relatively stable (Figure 2B-E). Kaplan-Meier survival curves further confirmed that high expression of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 was associated with reduced OS, with AP1AR and AP1S3 showing the strongest effects (Figure 2F-H). A forest plot integrating HRs across cohorts validated AP1AR and AP1S3 as independent adverse prognostic markers (Figure 2I), whereas AP1M2 and AP1B1 showed modest survival effects (Supplementary Figure S2). Extended analyses in TCGA-LUSC and combined TCGA-LUAD_LUSC cohorts confirmed the LUAD-specific prognostic relevance of AP1AR and AP1S3 (Supplementary Figure S3A-B). DepMap gene-effect profiles indicated moderate dependency of LUAD cell lines on these genes, supporting their role in tumor viability (Supplementary Figure S3C). Integration with TCGA methylation data revealed consistent promoter hypomethylation for AP1AR and AP1S3 in LUAD (Supplementary Figure S4A-C), correlating with elevated transcript levels. LUSC analyses showed weaker but directionally consistent trends (Supplementary Figure S4D-F), suggesting that transcriptional activation of these genes is at least partly epigenetically regulated.

Pan-cancer expression and overall survival associations of AP-1 adaptor genes. (A, C, E) Boxplots showing expression of AP1AR (A), AP1S1 (C), and AP1S3 (E) across TCGA cancer types, comparing tumor (red) and normal (blue) samples. Expression is shown in log2 TPM+1. Cancer types are indicated on the x-axis. (B, D, F) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for high vs low expression of AP1AR (B), AP1S1 (D), and AP1S3 (F). Log-rank p values, Cox hazard ratios (HRs), and the number of patients in each group are indicated in the plots.

Expression, stage distribution, and survival associations of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). (A) Multivariate Cox regression-based volcano plot from the SurvivalGenie platform highlighting AP1S3 and AP1AR as adverse prognostic genes (HR > 1, p < 0.05). Gray dots indicate non-significant genes (p > 0.05). (B) Boxplots comparing AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 expression between normal and LUAD tumor tissues. (C-E) Stage-specific expression patterns for AP1AR (C), AP1S1 (D), and AP1S3 (E), showing progressive upregulation of AP1AR and AP1S3 with advancing tumor stage, while AP1S1 remained relatively stable. (F-H) Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for AP1AR (F), AP1S1 (G), and AP1S3 (H), indicating that high expression correlates with poorer survival, with AP1AR and AP1S3 showing the strongest effects. (I) Forest plot summarizing hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals across datasets for AP1S3, AP1S1 and AP1AR, confirming AP1AR and AP1S3 as independent adverse prognostic markers in LUAD.

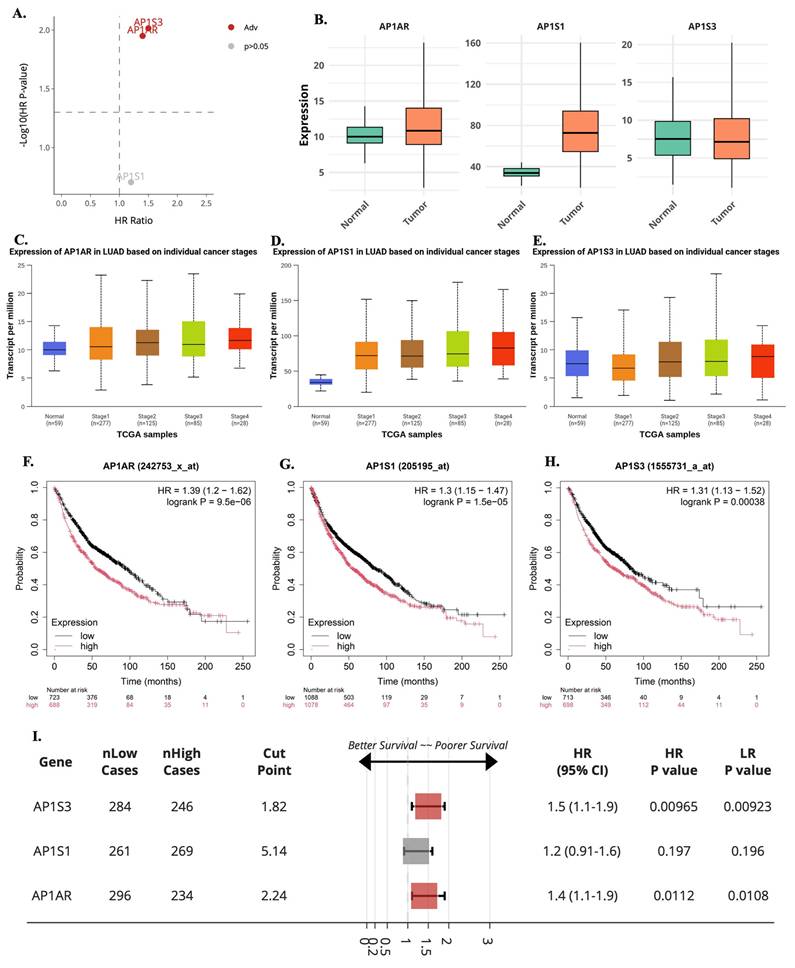

3.2 Functional Pathway Enrichment of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3

To explore the biological roles of the most relevant AP-1 adaptor genes, we performed GSEA on TCGA-LUAD expression profiles. AP1AR was strongly enriched in pathways related to EMT, hypoxia, inflammatory response, and cell-cycle progression, highlighting its role in proliferation and tumor aggressiveness (Figure 3A, D). AP1S1 showed enrichment for IL6-JAK-STAT3 and TNFα-NFκB signaling, as well as apoptosis and G2/M checkpoint pathways, suggesting involvement in both metabolic regulation and tumor-immune interactions (Figure 3B, E). AP1S3 was enriched in oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid metabolism, and cell-cycle checkpoint control, indicating a link to metabolic rewiring and stress adaptation (Figure 3C, F). Supplementary analyses confirmed that other AP-1 adaptor genes were also associated with hallmark cancer pathways, including hypoxia, apoptosis, metabolism, and EMT, supporting a broader oncogenic role for the family (Supplementary Figure S5). Parallel enrichment analyses in the TCGA-LUSC cohort showed similar patterns for AP1AR (Supplementary Figure S6A, D), AP1S1 (Supplementary Figure S6B, E), and AP1S3 (Supplementary Figure S6C, F), involving EMT, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, apoptosis, and G2/M checkpoint pathways. These results indicate that transcriptional programs associated with AP-1 adaptor dysregulation are largely conserved across lung cancer histotypes.

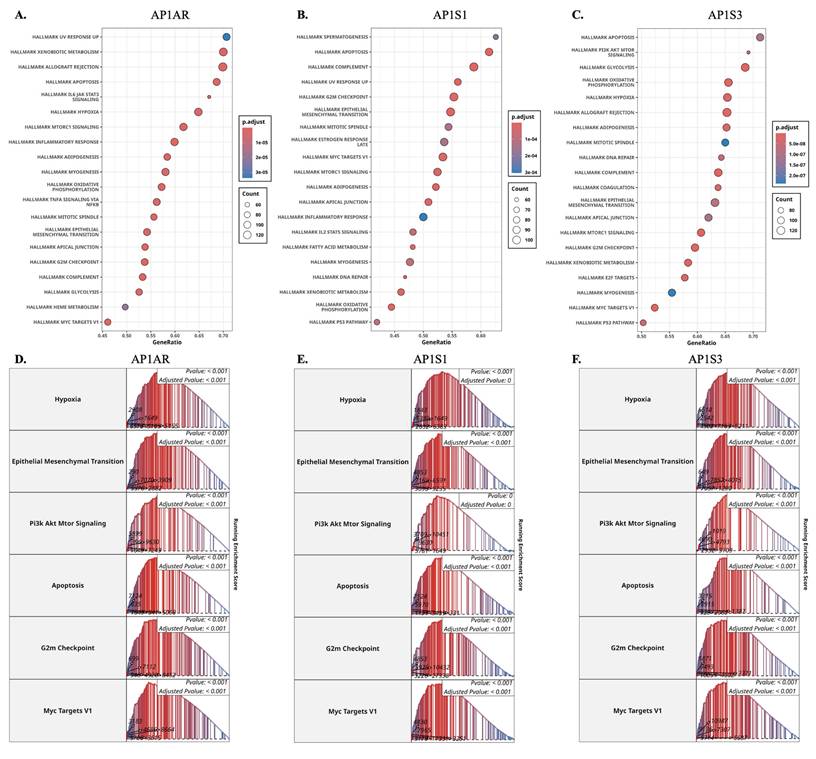

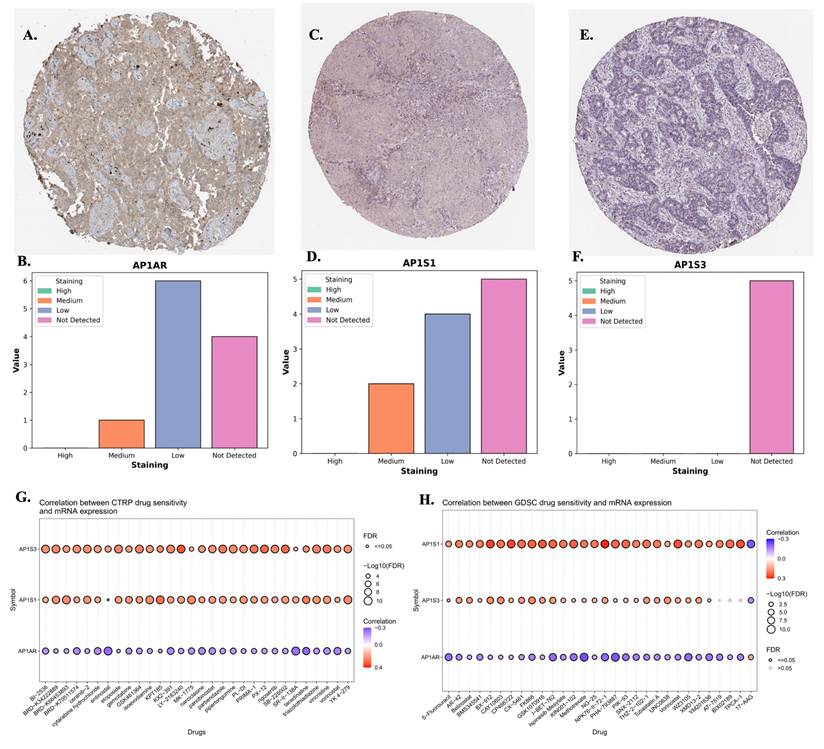

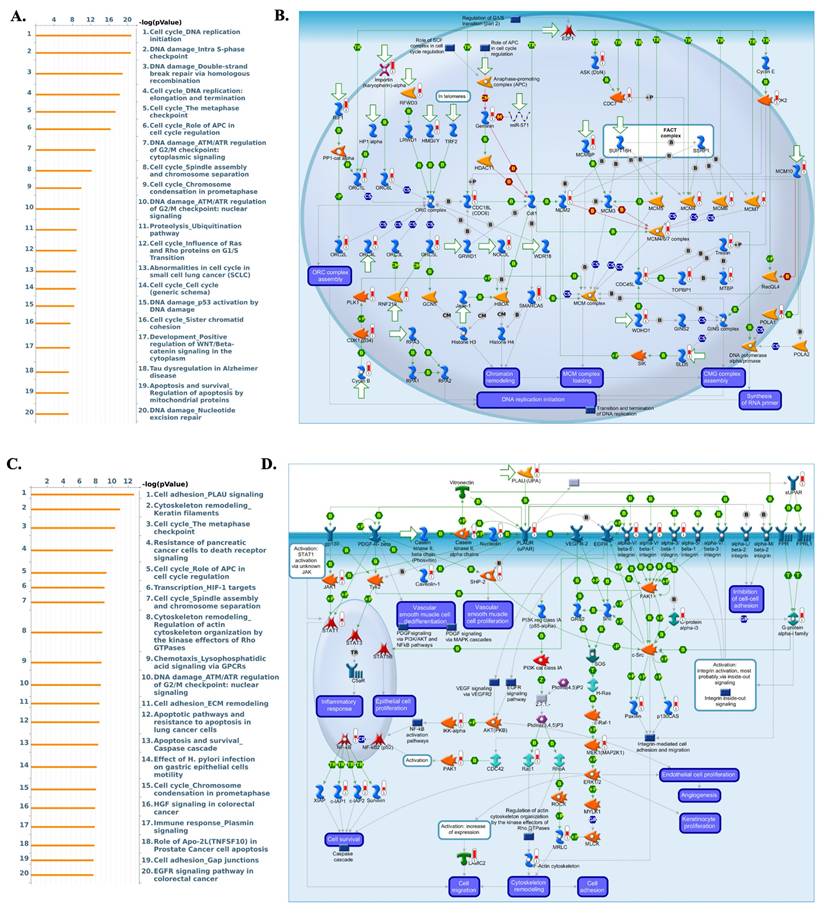

3.3 Protein-Level Validation, Drug Sensitivity Correlations, and MetaCore Analysis

To validate transcriptomic findings, protein expression of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 was assessed using IHC data from the HPA. AP1AR showed detectable cytoplasmic and membranous staining in LUAD tissues, whereas AP1S1 was weakly expressed and AP1S3 minimally detected (Figure 4A, C, E). Quantitative summaries confirmed higher protein-level prevalence of AP1AR compared with the other two genes (Figure 4B, D, F). Drug sensitivity correlations were analyzed using GSCA, CTRP, and GDSC datasets. Elevated AP1AR expression was associated with relative resistance to multiple chemotherapeutic agents and targeted inhibitors (Figure 4G, H), whereas AP1S1 and AP1S3 correlated with increased sensitivity to specific small-molecule drugs, indicating differential therapeutic implications among adaptor family members. Supplementary analyses revealed that AP1M2 and AP1B1 were also associated with drug sensitivity in select contexts (Supplementary Figure S7). To gain mechanistic insights, MetaCore pathway analyses were performed for AP1AR and AP1S3, the two most clinically significant genes. AP1AR was primarily linked to cell-cycle regulation and DNA replication checkpoints, suggesting a role in sustaining tumor proliferation (Figure 5A-B). In contrast, AP1S3 was associated with PI3K/AKT signaling and immune/inflammatory cross-talk pathways, highlighting its involvement in integrating oncogenic and microenvironmental signals (Figure 5C-D). Supplementary analyses further revealed enrichment of AP1AR in cytoskeletal remodeling and adhesion pathways, and AP1S3 in extracellular matrix remodeling and adhesion pathways (Supplementary Figure S8).

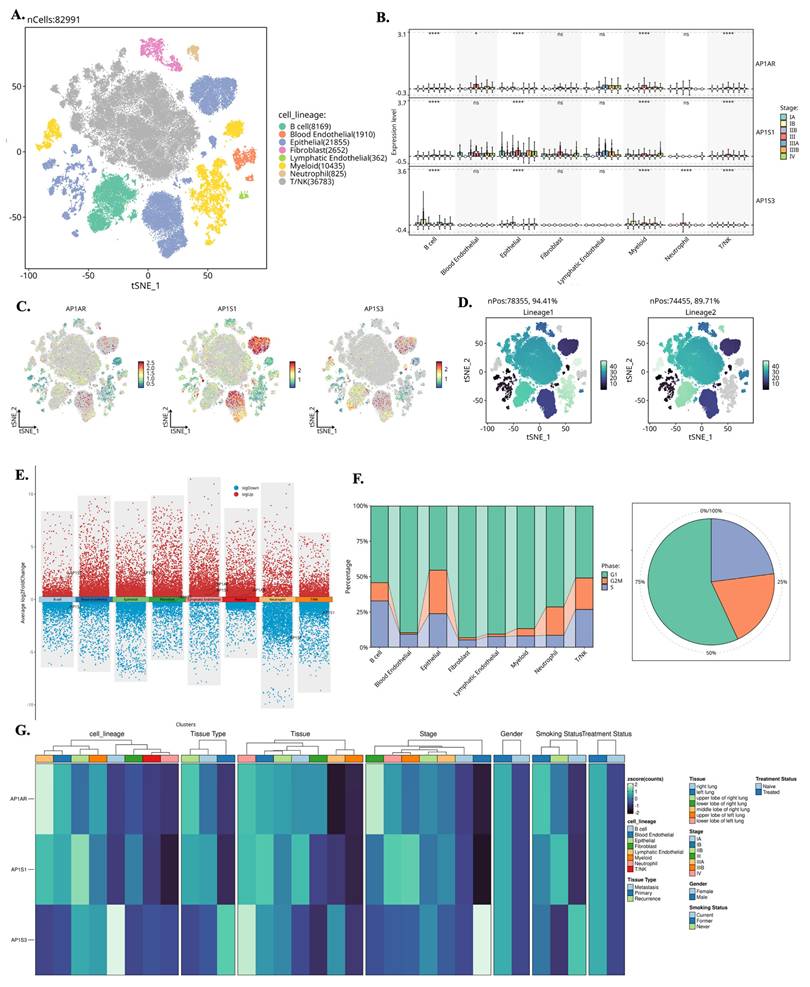

3.4 Single-Cell Localization of AP-1 Adaptor Gene Expressions

We analyzed single-cell RNA-seq data from GSE202159 to determine the cellular distributions and transcriptional contexts of AP-1 adaptor genes. Across ~83,000 cells, AP1AR and AP1S3 were predominantly expressed in malignant epithelial and fibroblast populations, with minimal detection in immune clusters (Figure 6A-C). Lineage-specific pseudotime trajectories constructed using Slingshot revealed progressive activation of AP1AR along epithelial and fibroblast branches, consistent with a proliferative trajectory (Figure 6D). Differential-expression mapping highlighted widespread transcriptional upregulation associated with AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3, implicating them in proliferative and stress-response programs (Figure 6E). Cell-cycle analysis demonstrated that most AP1AR- and AP1S3-positive cells resided in S and G2/M phases, indicating enrichment within proliferative cell types (Figure 6F). Integration with clinical annotations showed higher AP1AR and AP1S3 expression in advanced-stage tumors and smoker-associated samples compared to non-tumor tissues, suggesting a link to aggressive disease phenotypes (Figure 6G). Supplementary analyses confirmed these patterns: AP1M1, AP1B1, and AP1G1 exhibited moderate epithelial enrichment, whereas AP1M2 was sparsely expressed (Supplementary Figure S9). Trajectory inferences using the SCP package revealed dynamic temporal regulation of AP1AR and AP1S3. t-SNE visualizations illustrated AP1AR expression across metastatic, primary, and recurrent samples, with higher signals in cells annotated as S and G2/M phases (Supplementary Figure S10A, B). Correlation analyses revealed significant associations between AP1AR expression and DNA-repair-related genes (Supplementary Figure S10C). Pseudotime trajectories depicted progressive AP1AR activation along EMT-like branches and mid-trajectory peaks for AP1S3, consistent with complementary roles in proliferation and stress adaptation (Supplementary Figure S10D-G).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of AP-1 adaptor genes in lung cancer. (A-C) Dot plots showing significantly enriched Hallmark pathways associated with AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 expression in LUAD samples. Dot size represents gene count, and dot color indicates adjusted p-values. (D-F) Representative enrichment plots highlighting key Hallmark pathways, including Hypoxia, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition, PI3K/AKT/MTOR signaling, Apoptosis, G2M checkpoint, and MYC Targets V1 for AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3.

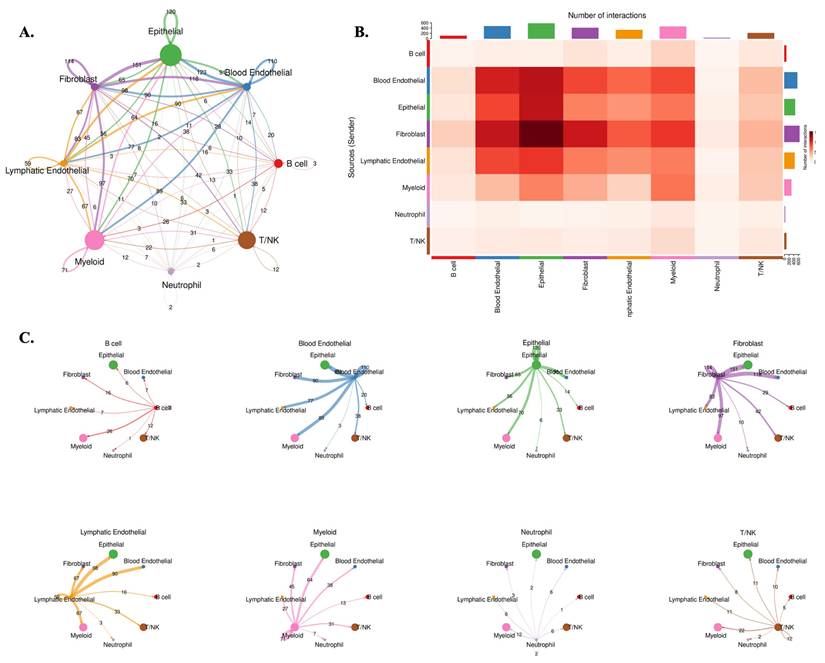

3.5 Microenvironmental Communication Networks Associated with AP1AR Expression

To investigate how AP1AR influences tumor-stromal interactions, we performed CellChat analysis, stratifying tumors by AP1AR expression. The AP1AR-high group exhibited markedly enhanced intercellular communication within the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Figure 7). In these tumors, fibroblast and epithelial populations acted as dominant signaling hubs, with extensive outgoing and incoming interactions involving myeloid and T/NK cells (Figure 7A-C). These interactions were enriched in growth factor- and cytokine-mediated pathways, including TGFB1-TGFBR2, IL6-IL6R, and EGF-EGFR signaling, suggesting that AP1AR upregulation amplifies paracrine networks supporting tumor proliferation and immune remodeling. In contrast, AP1AR-low tumors displayed globally reduced communication densities and weaker cross-lineage connectivity (Supplementary Figure S11), with the most pronounced loss observed in fibroblast-to-epithelial and immune-to-tumor signaling. Quantitative summaries confirmed decreased pathway activity and reduced ligand-receptor diversity, highlighting AP1AR expression as a key determinant of intercellular signaling intensity in lung cancer. Together, these results indicate that AP1AR overexpression not only drives intrinsic tumor proliferation but also promotes a communication-intensive TME, characterized by epithelial-fibroblast crosstalk and immune modulation, consistent with its enrichment in EMT and cytokine-response pathways observed in GSEA results.

Protein expressions and drug-sensitivity correlations of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3. (A, C, E) Representative immunohistochemical (IHC) images from the Human Protein Atlas showing AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 staining, respectively, in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) tissues. (B, D, F) Semi-quantitative distribution of staining intensities (high, medium, low, not detected) across LUAD samples, indicating that AP1AR is more frequently detected at the protein level than AP1S1 and AP1S3. (G) Correlations between AP1S3, AP1S1 and AP1AR mRNA expression and drug sensitivity in cancer cell lines from the CTRP dataset. (H) Correlations between AP1S1, AP1S3 and AP1AR mRNA expression and drug sensitivity in the GDSC dataset. In (G-H), each bubble represents one drug; bubble color denotes the correlation coefficient (purple, negative; red, positive), and bubble size is proportional to -log10(FDR), with larger bubbles indicating stronger statistical significance.

4. Discussion

This study represents the first comprehensive analysis of the AP-1 adaptor gene family in lung cancer, integrating bulk RNA-seq, clinical outcomes, protein expressions, drug sensitivity correlations, pathway enrichment, DNA methylation, CRISPR dependency, intercellular signaling inference, and single-cell transcriptomic data. By systematically evaluating eight AP-1 adaptor genes, we identified AP1AR as consistently upregulated, associated with poor survival, linked to drug resistance, and enriched in hallmark oncogenic pathways. Integration of promoter methylation and CRISPR dependency profiles confirmed that this transcriptional upregulation reflects both epigenetic activation and functional relevance, underscoring the biological significance of AP1AR. Importantly, AP1AR has not previously been characterized in lung cancer, highlighting its novelty and potential clinical value.

Pathway enrichment analysis of AP1AR- and AP1S3-associated gene signatures in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). (A) Bar plot of the top 20 MetaCore pathways enriched in the AP1AR-associated module, showing predominant enrichment of cell-cycle regulation, DNA replication, and DNA-damage checkpoint pathways (x-axis: -log10 p-value). (B) Representative MetaCore network illustrating AP1AR-related cell-cycle and DNA-replication programs, including regulation of the G1/S transition, chromatin remodeling, and MCM/CMG complex loading. (C) Bar plot of the top 20 MetaCore pathways enriched in the AP1S3-associated module, highlighting PLAU-mediated cell adhesion, cytoskeleton and ECM remodeling, apoptosis, and growth-factor signaling. (D) Representative MetaCore map depicting PLAU/uPAR-integrin-VEGFR/EGFR signaling and downstream cascades that regulate integrin-mediated cell adhesion, actin cytoskeleton remodeling, cell migration, and angiogenesis.

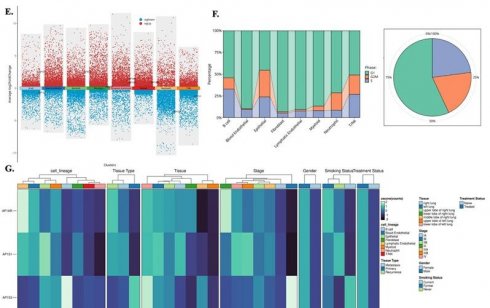

Single-cell transcriptomic landscape of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 in lung cancer. (A) t-SNE map of 82,991 cells from GSE202159 dataset, colored by major cell lineages. (B) Box plots showing normalized expression of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 across cell lineages and pathological stages, with highest expression in malignant epithelial and fibroblast cell types. (C) Feature plots of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 projected onto the t-SNE map, highlighting spatial localization of high-expressing clusters. (D) t-SNE maps illustrating lineage-level enrichment patterns (Lineage 1 and Lineage 2), indicating preferential accumulation of AP1AR-high cells within malignant epithelial subclusters. (E) Differential-expression analysis comparing AP1AR/AP1S1/AP1S3-high versus -low cells across lineages, shown as scatter plots of average log2 fold change; red and blue dots denote significantly upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. (F) Cell-cycle phase distribution of each lineage (stacked bar plots) and of all cells combined (pie chart), indicating the proportions of cells in G1/M, G2/M, and S phases. (G) Heatmap of AP1AR, AP1S1, and AP1S3 expression stratified by cell lineage, unsupervised cluster, tissue type (normal lung, primary tumor, recurrence), tumor stage, gender, smoking status, and treatment status, demonstrating consistent enrichment of AP1AR and AP1S3 in more aggressive tumor subsets.

Cell-cell communication landscape in AP1AR-high lung tumors. (A) Global intercellular communication network inferred by CellChat for AP1AR-high samples. Nodes represent major cell lineages (B cell, blood endothelial, epithelial, fibroblast, lymphatic endothelial, myeloid, neutrophil, and T/NK), with node size proportional to the total number of incoming and outgoing interactions; edge thickness reflects the overall communication probability between lineages. (B) Heatmap summarizing the number of significant ligand-receptor interactions from sender (rows) to receiver (columns); darker colors indicate a higher interaction count, highlighting intensive crosstalk among epithelial, fibroblast, and endothelial cell types. (C) Directional network plots for each lineage, illustrating its outgoing communication to other cell types. Arrow width denotes interaction strength, revealing fibroblast-, epithelial-, and endothelial-centered signaling hubs in AP1AR-high lung tumors.

Our analyses further validated AP1S3 as a clinically relevant adaptor gene, linking it to oncogenic signaling and immune-related pathways, while AP1S1 showed associations with metabolic reprogramming and immune regulation. Cross-histotype analyses in LUSC confirmed that both AP1AR and AP1S3 activate convergent EMT, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and apoptosis pathways. Single-cell transcriptomics localized AP1AR and AP1S3 primarily to malignant epithelial and fibroblast cell types, particularly in proliferative states, with pseudotime trajectories revealing progressive activation along EMT-like branches. At the mechanistic level, CellChat modeling indicated that AP1AR-high tumors exhibit a communication-intensive tumor microenvironment, with fibroblast and epithelial populations acting as signaling hubs for immune and stromal interactions. Conversely, AP1AR-low tumors displayed diminished intercellular connectivity, particularly in fibroblast-to-epithelial and immune-to-tumor signaling, consistent with a dampened paracrine landscape. Functional enrichment analyses (GSEA, MetaCore) implicated AP1AR in cell-cycle progression, DNA replication checkpoints, hypoxia, and EMT, while AP1S3 was linked to PI3K/AKT, KRAS, NF-κB, and MYC target pathways, connecting adaptor biology to both proliferation and immune modulation. Protein-level validation via IHC confirmed detectable AP1AR in tumor tissues, aligning with transcriptional and functional findings. CRISPR dependency screens indicated that AP1AR contributes to LUAD cell fitness, supporting a non-redundant role in tumor maintenance. Pharmacogenomic analyses revealed that AP1AR upregulation correlates with resistance to chemotherapeutics and targeted inhibitors, whereas AP1S1, AP1S3, AP1M2, and AP1B1 showed context-dependent associations with drug sensitivity. Network analyses placed AP1AR centrally within AP-1 adaptor-associated protein interaction space, consistent with curated protein-protein associations and enrichment data.

Overall, these converging multi-omics findings highlight AP1AR and AP1S3 as the most clinically relevant AP-1 adaptors in lung cancer, elucidating their roles in proliferation, stress adaptation, immune modulation, and drug response. This framework provides a strong foundation for biomarker development and hypothesis-driven therapy selection, offering insights into the broader contributions of AP-1 adaptor biology to lung tumorigenesis and the tumor microenvironment. Our results further reinforced these findings of AP1S3 by linking adaptor biology to oncogenic signaling and immune pathways, while AP1S1 showed associations with metabolic reprogramming and immune regulation. The inclusion of LUSC GSEA results strengthened this conclusion, showing that both AP1AR and AP1S3 activate convergent EMT, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and apoptosis signatures across histological subtypes. Single-cell analyses underpinned these results by grounding them in the TME, revealing that AP1AR and AP1S3 are preferentially expressed in malignant epithelial and fibroblast cell types, particularly during proliferative states. An additional pseudotime reconstruction demonstrated progressive activation of AP1AR along EMT-like trajectories, and the CellChat analysis revealed attenuated fibroblast-epithelial and immune-tumor signaling in AP1AR-low contexts, suggesting that adaptor regulation may influence both proliferation and intercellular communication. These inferences are consistent with the established roles of AP-1 adaptors in TGN-to-endosome trafficking and signaling homeostasis, and with CellChat's validated framework for network-level communication inference [81].

The most interesting finding is the involvement of AP1AR across multiple analytic layers. AP1AR expression was elevated in LUAD compared to normal tissues and demonstrated a strong association with OS. We additionally observed marked promoter hypomethylation in tumor samples, supporting an epigenetic mechanism for AP1AR activation. Unlike other AP-1 adaptor family members, AP1AR has not, to our knowledge, been functionally characterized in lung cancer; nevertheless, external resources document variable tumor protein detection, which aligns with our IHC observations. CRISPR dependency screening confirmed that AP1AR moderately contributes to the fitness of lung-cancer cells, implying a non-redundant role in growth maintenance, and these interpretations are supported by the robustness and cross-study concordance of modern CRISPR dependency resources. GSEA and MetaCore analyses implicated AP1AR in cell-cycle progression, DNA-replication checkpoints, hypoxia, and EMT hallmark processes of tumor aggressiveness. Pseudotime trajectories further revealed that AP1AR expression peaks during G2/M and EMT-associated transitions, paralleling enrichment for DNA-repair gene signatures. Moreover, high AP1AR expression was correlated with resistance to chemotherapeutics and targeted agents, suggesting potential clinical implications for therapy stratification. CellChat modeling added a layer of interpretation, as AP1AR-low tumors exhibited globally reduced network connectivity, particularly between the stromal and epithelial cell types, consistent with a dampened paracrine signaling landscape. At the protein level, AP1AR was detectable by IHC, further validating its biological relevance. Single-cell analyses localized AP1AR to malignant epithelial clusters enriched in proliferative phases, providing strong evidence that it may act directly within tumor-driving cell types. Our analyses identified AP1S3 as a second clinically relevant AP-1 adaptor gene in lung cancer. AP1S3 was significantly upregulated in tumors and associated with poorer survival. Pathway analyses linked it to PI3K/AKT, KRAS, NF-κB-driven inflammatory responses, and MYC target activation, consistent with prior evidence that AP1S3 modulates keratinocyte autophagy and enhances IL-36-dependent inflammatory signaling, connecting adaptor biology to immune pathways with potential oncogenic effects. AP1S1 was also elevated, though with more modest survival associations; it regulates EGFR trafficking in NSCLC, and its perturbation promotes lysosomal EGFR degradation and alters TKI response, while literature links STAT3 activity to oxidative phosphorylation and therapy resistance, supporting an immune-metabolic interpretation [82, 83].

Other family members showed variable contributions. AP1B1 and AP1G1 participate in receptor trafficking, including EGFR polarity and recycling, and depletion of AP-1 or partners such as GGA2 reduces EGFR surface levels and suppresses growth. AP-1 and RAB12 cooperate in post-EGF trafficking steps that modulate downstream signaling outputs [84, 85]. AP1M2 was enriched in apoptotic and hypoxia-related pathways, whereas AP1S2 and AP1M1 exhibited heterogeneous expression and weaker survival associations. Pharmacogenomic analyses suggested that AP1M2 and AP1B1 sensitize cells to selected small-molecule inhibitors. Network analysis positioned AP1AR centrally within the AP-1 adaptor protein interaction network, consistent with curated protein-protein association and enrichment data. Overall, family-wide trends collectively highlight cell-cycle control, hypoxia responses, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and tumor-stroma communication, providing a framework for biomarker development and hypothesis-driven therapy selection [86-88].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our integrated multi-omics and single-cell analyses identify AP1AR as the most consistent AP-1 adaptor signal in lung cancer, with the strongest evidence in adenocarcinoma. AP1AR shows transcriptional upregulation, independent associations with survival, promoter hypomethylation, enrichment of proliferation and epithelial to mesenchymal transition programs, and localization to tumor-driving cell types with altered stromal communication when low. These convergent layers nominate AP1AR as a clinically relevant biomarker and a candidate for translational prioritization, including hypothesis driven therapy stratification that will require prospective validation. Overall, the AP-1 adaptor complex emerges as an underexplored contributor to lung cancer biology. AP1AR stands out as a tractable focus for future mechanistic studies, biomarker development, and clinical evaluation aimed at therapy selection guided by adaptor gene expression.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH111-1M61, KMUH111-1M62, KMUH112-2M52, and KMUH113-3M49), the National Science and Technology Council (under grants 113-2320-B-393-001, 114-2320-B-393-003, 114-2320-B-393-004, 114-2314-B-038-133-MY3 and 114-2811-B-038-046), and the “TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine” from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan. The authors appreciate the professional English editing by Daniel P. Chamberlin from the Office of Research and Development at Taipei Medical University. The authors thank the statistical/computational/technical support of the Clinical Data Center, Office of Data Science, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan. The authors acknowledge the online platform for data analysis and visualization (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/). We also thank the statistical/computational/technical support of the Clinical Data Center, Office of Data Science, Taipei Medical University.

Data availability statement

All datasets used in this study are publicly available. Supporting data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68:394-424

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17-48

3. Chen CL, Tseng PC, Chao YP, Shen TJ, Jhan MK, Wang YT. et al. Polypeptide antibiotic actinomycin D induces Mcl-1 uncanonical downregulation in lung cancer cell apoptosis. Life Sci. 2023;321:121615

4. Tseng P-C, Chen C-L, Lee K-Y, Feng P-H, Wang Y-C, Satria RD. et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition hinders interferon-γ-dependent immunosurveillance in lung cancer cells. Cancer Letters. 2022;539:215712

5. Wu SY, Chen CL, Tseng PC, Chiu CY, Lin YE, Lin CF. Fractionated ionizing radiation facilitates interferon-γ signaling and anticancer activity in lung adenocarcinoma cells. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:16003-10

6. Robinson MS. Adaptable adaptors for coated vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:167-74

7. Salarolli RT, Alvarenga L, Cardozo L, Teixeira KTR, de SGML, Lima JD. et al. Can curcumin supplementation reduce plasma levels of gut-derived uremic toxins in hemodialysis patients? A pilot randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53:1231-8

8. Zatreanu D, Robinson HMR, Alkhatib O, Boursier M, Finch H, Geo L. et al. Polθ inhibitors elicit BRCA-gene synthetic lethality and target PARP inhibitor resistance. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3636

9. Szymanski EA, Henriksen J. Reconfiguring the Challenge of Biological Complexity as a Resource for Biodesign. mSphere. 2022;7:e0054722

10. Feng F, Yu S, Wang Z, Wang J, Park J, Wilson G. et al. Non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions relieve insomnia symptoms by modulating a shared network: A controlled longitudinal study. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;22:101745

11. Jeong J, Hwang YE, Lee M, Keum S, Song S, Kim JW. et al. Downregulation of AP1S1 causes the lysosomal degradation of EGFR in non-small cell lung cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2023;238:2335-47

12. Xiao D, Wang Q, Yan H, Lv X, Zhao Y, Zhou Z. et al. Adipose-derived stem cells-seeded bladder acellular matrix graft-silk fibroin enhances bladder reconstruction in a rat model. Oncotarget. 2017;8:86471-87

13. Lin JC, Liu TP, Chen YB, Huang TS, Chen TY, Yang PM. Inhibition of CDK9 exhibits anticancer activity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via targeting ribonucleotide reductase. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2023;471:116568

14. Lin JC, Liu TP, Chen YB, Yang PM. PF-429242 exhibits anticancer activity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via FOXO1-dependent autophagic cell death and IGFBP1-dependent anti-survival signaling. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:4125-44

15. Hsieh YY, Du JL, Yang PM. Repositioning VU-0365114 as a novel microtubule-destabilizing agent for treating cancer and overcoming drug resistance. Mol Oncol. 2024;18:386-414

16. Hsieh YY, Cheng YW, Wei PL, Yang PM. Repurposing of ingenol mebutate for treating human colorectal cancer by targeting S100 calcium-binding protein A4 (S100A4). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2022;449:116134

17. Ko CC, Yang PM. Hypoxia-induced MIR31HG expression promotes partial EMT and basal-like phenotype in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma based on data mining and experimental analyses. J Transl Med. 2025;23:305

18. Hoadley KA, Yau C, Hinoue T, Wolf DM, Lazar AJ, Drill E. et al. Cell-of-Origin Patterns Dominate the Molecular Classification of 10,000 Tumors from 33 Types of Cancer. Cell. 2018;173:291-304.e6

19. Zhang JX, Wang L, Hou HY, Yue CL, Wang L, Li HJ. Age-related impairment of navigation and strategy in virtual star maze. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:108

20. Cao J, Spielmann M, Qiu X, Huang X, Ibrahim DM, Hill AJ. et al. The single-cell transcriptional landscape of mammalian organogenesis. Nature. 2019;566:496-502

21. Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi B. et al. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19:649-58

22. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014; 511: 543-50.

23. Chiang YC, Wang CY, Kumar S, Hsieh CB, Chang KF, Ko CC. et al. Metal ion transporter SLC39A14-mediated ferroptosis and glycosylation modulate the tumor immune microenvironment: pan-cancer multi-omics exploration of therapeutic potential. Cancer Cell Int. 2025;25:363

24. Su BH, Kumar S, Cheng LH, Chang WJ, Solomon DD, Ko CC. et al. Multi-omics profiling reveals PLEKHA6 as a modulator of β-catenin signaling and therapeutic vulnerability in lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2025;15:3106-27

25. Xuan DTM, Yeh IJ, Liu HL, Su CY, Ko CC, Ta HDK. et al. A comparative analysis of Marburg virus-infected bat and human models from public high-throughput sequencing data. Int J Med Sci. 2025;22:1-16

26. Dwivedi B, Mumme H, Satpathy S, Bhasin SS, Bhasin M. Survival Genie, a web platform for survival analysis across pediatric and adult cancers. Sci Rep. 2022;12:3069

27. Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W556-w60

28. Györffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q. et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725-31

29. Kumar S, Wu CC, Wulandari FS, Chiao CC, Ko CC, Lin HY. et al. Integration of multi-omics and single-cell transcriptome reveals mitochondrial outer membrane protein-2 (MTX-2) as a prognostic biomarker and characterizes ubiquinone metabolism in lung adenocarcinoma. J Cancer. 2025;16:2401-20

30. Xuan DTM, Wu CC, Wang WJ, Hsu HP, Ta HDK, Anuraga G. et al. Glutamine synthetase regulates the immune microenvironment and cancer development through the inflammatory pathway. Int J Med Sci. 2023;20:35-49

31. Xuan DTM, Yeh IJ, Su CY, Liu HL, Ta HDK, Anuraga G. et al. Prognostic and Immune Infiltration Value of Proteasome Assembly Chaperone (PSMG) Family Genes in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Int J Med Sci. 2023;20:87-101

32. Goldman M, Craft B, Hastie M, Repečka K, McDade F, Kamath A. et al. The UCSC Xena platform for public and private cancer genomics data visualization and interpretation. biorxiv. 2018: 326470.

33. Arafeh R, Shibue T, Dempster JM, Hahn WC, Vazquez F. The present and future of the Cancer Dependency Map. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2025;25:59-73

34. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A. et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419

35. Chiao CC, Liu YH, Phan NN, An Ton NT, Ta HDK, Anuraga G. et al. Prognostic and Genomic Analysis of Proteasome 20S Subunit Alpha (PSMA) Family Members in Breast Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 11

36. Anuraga G, Wang WJ, Phan NN, An Ton NT, Ta HDK, Berenice Prayugo F. et al. Potential Prognostic Biomarkers of NIMA (Never in Mitosis, Gene A)-Related Kinase (NEK) Family Members in Breast Cancer. J Pers Med. 2021 11

37. Ta HDK, Wang WJ, Phan NN, An Ton NT, Anuraga G, Ku SC. et al. Potential Therapeutic and Prognostic Values of LSM Family Genes in Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021 13

38. Liu CJ, Hu FF, Xie GY, Miao YR, Li XW, Zeng Y. et al. GSCA: an integrated platform for gene set cancer analysis at genomic, pharmacogenomic and immunogenomic levels. Brief Bioinform. 2023 24

39. Rees MG, Seashore-Ludlow B, Cheah JH, Adams DJ, Price EV, Gill S. et al. Correlating chemical sensitivity and basal gene expression reveals mechanism of action. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:109-16

40. Iorio F, Knijnenburg TA, Vis DJ, Bignell GR, Menden MP, Schubert M. et al. A Landscape of Pharmacogenomic Interactions in Cancer. Cell. 2016;166:740-54

41. Wu YJ, Chiao CC, Chuang PK, Hsieh CB, Ko CY, Ko CC. et al. Comprehensive analysis of bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data reveals Schlafen-5 (SLFN5) as a novel prognosis and immunity. Int J Med Sci. 2024;21:2348-64

42. Anuraga G, Lang J, Xuan DTM, Ta HDK, Jiang JZ, Sun Z. et al. Integrated bioinformatics approaches to investigate alterations in transcriptomic profiles of monkeypox infected human cell line model. J Infect Public Health. 2024;17:60-9

43. Wang CY, Xuan DTM, Ye PH, Li CY, Anuraga G, Ta HDK. et al. Synergistic suppressive effects on triple-negative breast cancer by the combination of JTC-801 and sodium oxamate. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:4661-77

44. Korotkevich G, Sukhov V, Sergushichev A. Fast gene set enrichment analysis. bioRxiv. 2019: 060012.

45. Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417-25

46. Wang CY, Chao YJ, Chen YL, Wang TW, Phan NN, Hsu HP. et al. Upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and the lipid metabolism pathway promotes carcinogenesis of ampullary cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:256-69

47. Liu HL, Yeh IJ, Phan NN, Wu YH, Yen MC, Hung JH. et al. Gene signatures of SARS-CoV/SARS-CoV-2-infected ferret lungs in short- and long-term models. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;85:104438

48. Wu YH, Yeh IJ, Phan NN, Yen MC, Hung JH, Chiao CC. et al. Gene signatures and potential therapeutic targets of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)-infected human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54:845-57

49. Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M, Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D638-d46

50. Glasner A, Rose SA, Sharma R, Gudjonson H, Chu T, Green JA. et al. Conserved transcriptional connectivity of regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment informs new combination cancer therapy strategies. Nat Immunol. 2023;24:1020-35

51. Megill C, Martin B, Weaver C, Bell S, Prins L, Badajoz S. et al. cellxgene: a performant, scalable exploration platform for high dimensional sparse matrices. bioRxiv. 2021. 2021 04.05.438318

52. Solomon DD, Ko CC, Chen HY, Kumar S, Wulandari FS, Xuan DTM. et al. A machine learning framework using urinary biomarkers for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma prediction with post hoc validation via single-cell transcriptomics. Brief Bioinform. 2025 26

53. Li CY, Anuraga G, Chang CP, Weng TY, Hsu HP, Ta HDK. et al. Repurposing nitric oxide donating drugs in cancer therapy through immune modulation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:22

54. Hagerling C, Gonzalez H, Salari K, Wang CY, Lin C, Robles I. et al. Immune effector monocyte-neutrophil cooperation induced by the primary tumor prevents metastatic progression of breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:21704-14

55. Lee KT, Chen DP, Loh ZJ, Chung WP, Wang CY, Chen PS. et al. Benign polymorphisms in the BRCA genes with linkage disequilibrium is associated with cancer characteristics. Cancer Sci. 2024;115:3973-85

56. Chen HK, Chen YL, Wang CY, Chung WP, Fang JH, Lai MD. et al. ABCB1 Regulates Immune Genes in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2023;15:801-11

57. Chen YL, Lee KT, Wang CY, Shen CH, Chen SC, Chung WP. et al. Low expression of cytosolic NOTCH1 predicts poor prognosis of breast cancer patients. Am J Cancer Res. 2022;12:2084-101

58. Ye PH, Li CY, Cheng HY, Anuraga G, Wang CY, Chen FW. et al. A novel combination therapy of arginine deiminase and an arginase inhibitor targeting arginine metabolism in the tumor and immune microenvironment. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:1952-69

59. Jin S, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Zhang L, Chang I, Ramos R, Kuan CH. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1088

60. Mwale PF, Hsieh CT, Yen TL, Jan JS, Taliyan R, Yang CH. et al. Chitinase-3-like-1: a multifaceted player in neuroinflammation and degenerative pathologies with therapeutic implications. Mol Neurodegener. 2025;20:7

61. Chen IC, Lin HY, Liu ZY, Cheng WJ, Yeh TY, Yang WB. et al. Repurposing Linezolid in Conjunction with Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Access in the Realm of Glioblastoma Therapies. J Med Chem. 2025;68:2779-803

62. Shen CJ, Chen HC, Lin CL, Thakur A, Onuku R, Chen IC. et al. Contribution of Prostaglandin E2-Induced Neuronal Excitation to Drug Resistance in Glioblastoma Countered by a Novel Blood-Brain Barrier Crossing Celecoxib Derivative. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025: e06336.

63. Chen HC, Lin HY, Chiang YH, Yang WB, Wang CH, Yang PY. et al. Progesterone boosts abiraterone-driven target and NK cell therapies against glioblastoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43:218

64. Liu CC, Yang WB, Chien CH, Wu CL, Chuang JY, Chen PY. et al. CXCR7 activation evokes the anti-PD-L1 antibody against glioblastoma by remodeling CXCL12-mediated immunity. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15:434

65. Cassiano GC, Martinelli A, Mottin M, Neves BJ, Andrade CH, Ferreira PE. et al. Whole genome sequencing identifies novel mutations in malaria parasites resistant to artesunate (ATN) and to ATN + mefloquine combination. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1353057

66. Kwee I, Martinelli A, Khayal LA, Akhmedov M. metaLINCS: an R package for meta-level analysis of LINCS L1000 drug signatures using stratified connectivity mapping. Bioinform Adv. 2022;2:vbac064

67. Maseng MJ, Tawe L, Thami PK, Seatla KK, Moyo S, Martinelli A. et al. Association of CYP2B6 Genetic Variation with Efavirenz and Nevirapine Drug Resistance in HIV-1 Patients from Botswana. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2021;14:335-47

68. Wickham H. ggplot2. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: computational statistics. 2011;3:180-5

69. Xuan DTM, Wu CC, Kao TJ, Ta HDK, Anuraga G, Andriani V. et al. Prognostic and immune infiltration signatures of proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase (PSMD) family genes in breast cancer patients. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:24882-913

70. Choy TK, Wang CY, Phan NN, Khoa Ta HD, Anuraga G, Liu YH. et al. Identification of Dipeptidyl Peptidase (DPP) Family Genes in Clinical Breast Cancer Patients via an Integrated Bioinformatics Approach. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 11

71. Hinton PR, McMurray I, Brownlow C. SPSS explained: Routledge; 2014

72. Akhmedov M, Martinelli A, Geiger R, Kwee I. Omics Playground: a comprehensive self-service platform for visualization, analytics and exploration of Big Omics Data. NAR Genom Bioinform. 2020;2:lqz019

73. Tang D, Chen M, Huang X, Zhang G, Zeng L, Zhang G. et al. SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0294236

74. Wickham H, Sievert C. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis: Springer, New York; 2009

75. Chen PS, Hsu HP, Phan NN, Yen MC, Chen FW, Liu YW. et al. CCDC167 as a potential therapeutic target and regulator of cell cycle-related networks in breast cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:4157-81

76. Doyle SR, Tracey A, Laing R, Holroyd N, Bartley D, Bazant W. et al. Genomic and transcriptomic variation defines the chromosome-scale assembly of Haemonchus contortus, a model gastrointestinal worm. Commun Biol. 2020;3:656

77. Marks ND, Winter AD, Gu HY, Maitland K, Gillan V, Ambroz M. et al. Profiling microRNAs through development of the parasitic nematode Haemonchus identifies nematode-specific miRNAs that suppress larval development. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17594

78. Lin JC, Liu TP, Yang PM. CDKN2A-Inactivated Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Exhibits Therapeutic Sensitivity to Paclitaxel: A Bioinformatics Study. J Clin Med. 2020 9

79. Liu LW, Hsieh YY, Yang PM. Bioinformatics Data Mining Repurposes the JAK2 (Janus Kinase 2) Inhibitor Fedratinib for Treating Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma by Reversing the KRAS (Kirsten Rat Sarcoma 2 Viral Oncogene Homolog)-Driven Gene Signature. J Pers Med. 2020 10

80. Hsieh YY, Liu TP, Chou CJ, Chen HY, Lee KH, Yang PM. Integration of Bioinformatics Resources Reveals the Therapeutic Benefits of Gemcitabine and Cell Cycle Intervention in SMAD4-Deleted Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Genes (Basel). 2019 10

81. Robinson MS, Antrobus R, Sanger A, Davies AK, Gershlick DC. The role of the AP-1 adaptor complex in outgoing and incoming membrane traffic. J Cell Biol. 2024 223

82. Hu Y, Dong Z, Liu K. Unraveling the complexity of STAT3 in cancer: molecular understanding and drug discovery. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2024;43:23

83. Yang L, Ying S, Hu S, Zhao X, Li M, Chen M. et al. EGFR TKIs impair lysosome-dependent degradation of SQSTM1 to compromise the effectiveness in lung cancer. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2019;4:25

84. Uemura T, Suzuki T, Dohmae N, Waguri S. Clathrin adapters AP-1 and GGA2 support expression of epidermal growth factor receptor for cell growth. Oncogenesis. 2021;10:80

85. Cotton CU, Hobert ME, Ryan S, Carlin CR. Basolateral EGF receptor sorting regulated by functionally distinct mechanisms in renal epithelial cells. Traffic. 2013;14:337-54

86. Pacini C, Duncan E, Gonçalves E, Gilbert J, Bhosle S, Horswell S. et al. A comprehensive clinically informed map of dependencies in cancer cells and framework for target prioritization. Cancer Cell. 2024;42:301-16.e9

87. Wu F, Yang J, Liu J, Wang Y, Mu J, Zeng Q. et al. Signaling pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts and targeted therapy for cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2021;6:218

88. Asmerian H, Alberts J, Sanetra AM, Diaz AJ, Silm K. Role of adaptor protein complexes in generating functionally distinct synaptic vesicle pools. J Physiol. 2025;603:5889-901

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Chih-Yang Wang (chihyangedu.tw) and Meng-Chi Yen (yohococom).

Corresponding authors: Chih-Yang Wang (chihyangedu.tw) and Meng-Chi Yen (yohococom).

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact