Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2026; 17(1):109-116. doi:10.7150/jca.120666 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Association of Ion Concentration with Immune-Related Adverse Events and Prognosis in Lung Cancer Patients Treated with PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors

1. Xiangya School of Pharmacy, Central South University, Changsha 410078; P. R. China.

2. Department of Pharmacy, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410078; P. R. China.

3. Lung Cancer and Gastrointestinal Unit, Department of Medical Oncology, Hunan Cancer Hospital/The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University, Changsha 410031, P. R. China.

4. Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Hunan Key Laboratory of Pharmacogenetics, and National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008, P. R. China.

5. National Institution of Drug Clinical Trial, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008, P. R. China.

6. The Hunan Institute of Pharmacy Practice and Clinical Research, Changsha 410008, P. R. China.

7. Department of Pharmacy, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, 310009, P. R. China.

Received 2025-6-30; Accepted 2025-11-6; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

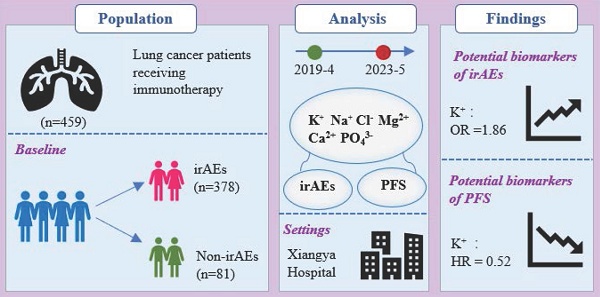

Objectives: irAEs were associated with immunotherapy response in cancer treatment, but severe irAEs discontinued immunotherapy and affected the quality of life. This study aimed to identify ion concentrations as potential biomarkers for irAEs and prognosis in lung cancer patients receiving ICI therapy.

Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted on 459 lung cancer patients who received ICI treatment at Xiangya Hospital from April 2019 to May 2023. Patient characteristics, ion concentrations (K+, Na+, Cl-, Ca2+, PO43- and Mg2+), irAEs, and prognosis were systematically collected. Univariable and multivariable regression analyses, including binary logistic regression and Cox regression models, were employed to identify factors associated with irAEs and PFS.

Results: Among 459 lung cancer patients receiving ICI treatment, 378 (82.4%) of the patients suffered irAEs. PD-L1 expression, ICI cycles, ORR and DCR were linked to irAEs occurrence. Cardiotoxicity, hypothyroidism, and dermatoxicity were the predominant irAEs types, but mostly mild to moderate. Notably, elevated potassium (K+) level was significantly correlated with both a higher risk of irAEs and longer PFS.

Conclusions: The findings suggest that K+ concentration prior to initiating treatment with ICIs may be a biomarker of irAEs and PFS in lung cancer patients.

Keywords: lung cancer, ICIs, irAEs, ion concentration, PFS, biomarkers

Introduction

Lung cancer ranks among the most common and lethal malignancies worldwide [1]. Most patients present with distant metastases at diagnosis, substantially complicating treatment [2]. Immunotherapy, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has significantly improved clinical prognosis [3, 4]. By activating cytotoxic T lymphocytes against tumors, ICIs yield considerable clinical benefits; however, this broad immune activation also leads to immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in 60-80% of patients, most commonly affecting the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and endocrine systems [5-7]. For instance, immune-mediated diarrhea and colitis often occur 4 to 6 weeks after treatment initiation [8]. As immunotherapy is widely used to identify biomarkers and risk factors for predicting toxicity has become increasingly important [9-12].

Ions include potassium (K+), sodium (Na+), magnesium (Mg2+), calcium (Ca2+), chloride (Cl-), and phosphate (PO43-) which play vital roles in transcellular and intracellular signaling. These signaling processes are essential for immune activation and immunological memory [13-15]. Maintaining ionic balance is critical for cellular function and systemic physiological stability; its disruption may affect the tumor microenvironment (TME) [14, 16]. Within the TME, competition between T cells and tumor cells for essential ions can interfere with metabolic reprogramming and impair T cell-mediated antitumor responses [17, 18]. T cells, central to antitumor immunity, are activated upon T cell receptor (TCR) recognition of tumor antigen peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules [19]. Key T cell subsets, including cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), helper T cells (Th), and regulatory T cells (Tregs), orchestrate immune responses in the TME, and their interplay critically shapes the outcome of immunotherapy [20]. Consequently, ionic imbalance within the TME may substantially influence T cell function and thereby affect both the safety and efficacy of ICIs [21]. Emerging evidence suggests that metal ion-modulated immunotherapy represents a promising therapeutic strategy, with ions participating in early immune regulation [22], indicating that plasma ion levels may be linked to immunotherapy response and irAEs.

Therefore, this retrospective study aimed to evaluate the association between ion concentrations and the occurrence of irAEs as well as prognosis in lung cancer patients treated with ICIs.

Materials and Methods

Patient collection

The study population included 459 patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed diagnosis of lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors at Xiangya Hospital from April 2019 to May 2023. The ethics committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University approved this retrospective study (2022100970), and all patients have provided written informed consent.

Study assessments

Adverse events were graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Treatment responses were assessed using the Immune Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (iRECIST), with the objective response rate (ORR) defined as the proportion of patients achieving a confirmed complete or partial response (CR/PR) sustained for ≥ 4 weeks. The disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the proportion of patients with the best overall response of CR, PR, or stable disease (SD) lasting ≥ 12 weeks. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from immunotherapy initiation until radiologically confirmed disease progression per iRECIST, death from any cause, or the last valid tumor assessment date for censored observations.

Treatment and data collection

The clinical characteristics of patients were systematically collected, including age, ICIs treatment cycle, gender, smoking history, tumor histology, disease stage, immune checkpoint inhibitor type, metastasis status, treatment line, preexisting diseases, PD-L1 expression, driver mutation status, development of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). The clinical characteristics of the patients were summarized in Table 1. The ion concentration (K+, Na+, Cl-, Ca2+, PO43- and Mg2+) of the enrolled patients before the first application of immune checkpoint inhibitors were obtained by the medical records.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as means ± SD for normal distributions or medians (IQR) for skewed ones. Chi-square tests compared categorical variables, independent t-tests assessed normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for skewed ones. Binary logistic regression identified factors associated with irAEs. Cox regression models determined PFS-associated factors, with significant univariable variables entered into multivariable models. Cut-off values of high and low concentration of the ions for analyses of irAEs, ORR, and DCR were determined using ROC curves and Youden's index. The optimal PFS critical value was set using the surv_cutpoint() function in the survminer package. All analyses used SPSS 26.0 and R 4.1.1, with P< 0.05 indicating significance.

Patient characteristics of 459 lung cancer patients in this study.

| Characteristics | No. of patients (N=459) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-irAEs (%) (N=81) | irAEs (%) (N=378) | P | |

| Age | 0.371 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 60.2±8.1 | 61.1±8.4 | |

| <60 | 41 (50.6) | 155 (41.0) | 0.112 |

| ≥60 | 40 (49.4) | 223 (59.0) | |

| ICIs treatment cycle | 6.0 (4.0, 9.2) | 8.0 (4.0, 14.0) | 0.007 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 12 (14.8) | 50 (13.2) | 0.704 |

| Male | 69 (85.2) | 328 (86.8) | |

| Histology | 0.880 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 28 (34.6) | 134 (35.4) | |

| Non-Adenocarcinoma | 53 (65.4) | 244 (64.6) | |

| Stage | 0.464 | ||

| I/I | 4 (4.9) | 10 (2.6) | |

| III/IV | 77 (95.1) | 368 (97.4) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Former/current | 63 (77.8) | 298 (78.8) | 0.833 |

| Never | 18 (22.2) | 80 (21.2) | |

| Type of ICI | 0.660 | ||

| PD-1 | 69 (85.2) | 333 (88.1) | |

| PD-L1 | 10 (12.3) | 40 (10.6) | |

| PD-1/PD-L1 | 2 (2.5) | 5 (1.3) | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.129 | ||

| Yes | 43 (53.1) | 235 (62.2) | |

| No | 38 (46.91) | 143 (37.8) | |

| No. of Treatment line | 0.459 | ||

| 1 | 70 (86.4) | 314 (83.1) | |

| ≥2 | 11 (13.6) | 64 (16.9) | |

| Preexisting diseases | 0.549 | ||

| Yes | 57 (70.4) | 253 (66.9) | |

| No | 24 (29.6) | 125 (33.1) | |

| PD-L1 expression% | 0.005 | ||

| <1 | 9 /37(24.3) | 70/169 (41.4) | |

| 1-49 | 8 /37(21.6) | 54/169 (32.0) | |

| >50 | 20/37 (54.1) | 45 /169(26.6) | |

| EGFR mutation | 0.147 | ||

| Present | 5/41 (12.2) | 38/170 (22.4) | |

| Absent | 36/41 (87.8) | 132/170(77.6) | |

| ALK mutation | 0.616 | ||

| Present | 1/43 (2.4) | 2/153 (1.3) | |

| Absent | 41 /43(97.6) | 151/153(98.7) | |

| KRAS mutation | 0.272 | ||

| Present | 3/27 (11.1) | 34 /170(20.0) | |

| Absent | 24/27 (88.9) | 136/170(80.0) | |

| MET mutation | 0.279 | ||

| Present | 0/34 (0.0) | 5/149 (3.4) | |

| Absent | 34 /34(100.0) | 144/149(96.6) | |

| BRAF mutation | 0.196 | ||

| Present | 0 /36(0.0) | 6/134 (4.5) | |

| Absent | 36/36 (100.0) | 128/134(95.5) | |

| Best Response | 0.037 | ||

| CR | 1 (1.2) | 3 (0.8) | |

| PR | 40 (49.4) | 200 (52.9) | |

| SD | 29 (35.8) | 121 (32.0) | |

| PD | 3 (3.7) | 41 (10.8) | |

| N/E | 8 (9.9) | 13 (3.4) | |

| ORR (CR+PR) | 41 (50.6) | 203 (53.7) | 0.042 |

| DCR (CR+PR+SD) | 70 (86.4) | 324 (85.7) | 0.008 |

Footnote: CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; N/E, not evaluable; ORR, objective response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the patients

A total of 459 lung cancer patients who received immunotherapy were recruited in this study (Table 1). The irAEs occurred in 378 patients (82.4%). The median age of patients who developed irAEs were 61.1 ± 8.4 years compared with 60.2 ± 8.1 years among those who did not. Gender distribution was comparable (female [13.2%] and male [86.8%] with irAEs) vs (female [14.8%] and male [85.2%] without irAEs). The development of irAEs was significantly associated with a high expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (P = 0.005), number of ICI treatment cycles (P = 0.007), objective response rate (ORR, P = 0.042), and disease control rate (DCR, P = 0.008). In contrast, no significant associations were observed between irAEs and gender, age, tumor histology, disease stage, smoking history, type of ICI, line of treatment, preexisting diseases, or driver mutation status.

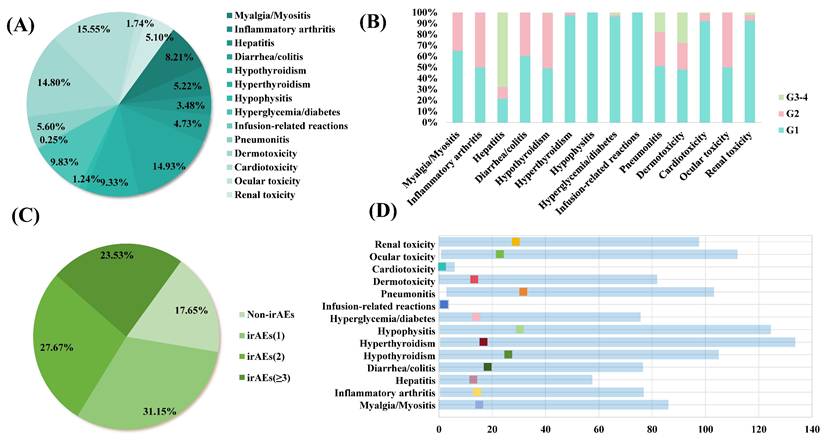

irAEs outcomes

The characteristics of irAEs are shown in Figure 1. The most prevalent immune-related adverse events (irAEs) were cardiotoxicity (15.55%), followed by hypothyroidism (14.93%), and dermotoxicity (14.80%) (Figure 1A). During the follow-up period, endocrine toxicity, musculoskeletal toxicity, and cardiotoxicity predominantly exhibited Grade 1-2 irAEs, while dermotoxicity and hepatitis had a higher incidence of high-grade (Grade 3-4) irAEs. Notably, most irAEs were mild to moderate in severity (Figure 1B). The majority of patients experienced either one or two types of irAEs (Figure 1C). The time of onset of each irAEs was different. Pneumonitis had the longest median onset of 31.73(2.87-103.16) weeks compared with other toxicities. However, Cardiotoxicity with a median onset of 1.27(0.01-5.97) weeks, indicating a relatively rapid onset compared to other irAEs (Figure 1D).

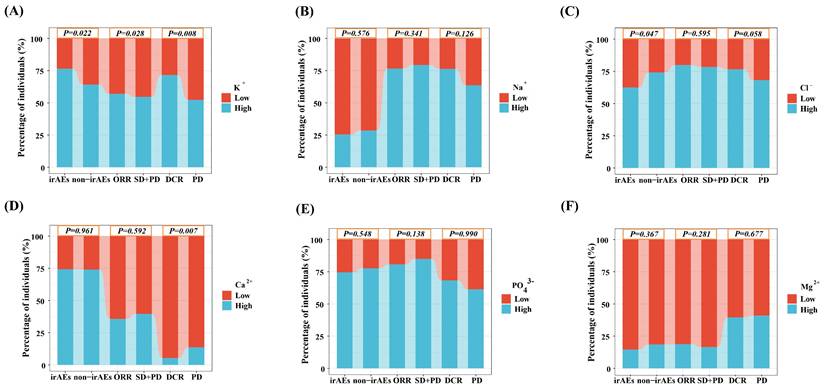

The association of ion concentrations with irAEs and treatment response

The ROC curve was used to determine the optimal cut-off values of ion concentrations (K+, Na+, Cl-, Ca2+, PO43- and Mg2+) for irAEs, ORR and DCR (Table S1). K+ concentration showed significant associations with irAEs, ORR, and DCR. A higher pre-treatment K+ concentration was significantly associated with an increased incidence of irAEs (76.46%; P = 0.022). It was also associated with improved ORR (56.97%; P = 0.028) and DCR (71.57%; P = 0.008), suggesting a potential role for K+ levels in predicting both toxicity and treatment response. Additionally, Cl- concentration showed a significant correlation with the occurrence of irAEs. Furthermore, Ca2+ concentration was associated with DCR, indicating a possible impact on treatment efficacy. In contrast, the lack of statistical significance in the association between Na+, PO43-, and Mg2+ concentrations and each clinical index may be attributed to insufficient sample size or the weak direct role of these ions in immune regulation (P > 0.05).

irAEs in lung cancer patients receiving ICIs. (A)The categories and proportions of irAEs. (B)The incidence of irAEs. (C) The proportions single or multiple irAEs. (D) Time to onset of irAEs.

Proportions of patients with irAEs, ORR, and DCR, stratified by serum ion levels. (A) Potassium. (B) Sodium. (C) Chloride. (D) Calcium. (E) Phosphate. (F) Magnesium.

K+ concentration associated with irAEs

Univariable and multivariable regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association between potassium (K⁺) concentration and immune-related adverse events (irAEs) (Table 2). In the univariable analysis, a higher K⁺ level was significantly associated with an increased risk of irAEs (OR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.08-3.01, P = 0.023). This association remained significant after multivariable adjustment (OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.10-3.11, P = 0.019). These results suggest that elevated K⁺ levels are a potential risk factor for irAEs.

Univariable and Multivariable analyses of irAEs (n = 459).

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (≥ 60 vs. < 60) | 1.47 (0.91-2.39) | 0.114 | ||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 1.14 (0.55-2.19) | 0.705 | ||

| ICIs treatment cycle | 1.06 (1.02-1.12) | 0.006 | 1.06(1.02-1.12) | 0.006 |

| Smoking status (former/current vs. never) | 1.06 (0.58-1.87) | 0.833 | ||

| Metastasis (yes vs. no) | 1.45 (0.89-2.35) | 0.130 | ||

| No. of treatment line (≥ 2 vs. 1) | 1.30 (0.67-2.71) | 0.460 | ||

| Preexisting diseases (yes vs. no) | 0.85 (0.50-1.42) | 0.549 | ||

| Histology (LUAD vs.non-LUAD) | 1.04 (0.63-1.74) | 0.880 | ||

| K+ (high vs. low) | 1.81 (1.08-3.01) | 0.023 | 1.86(1.10-3.11) | 0.019 |

K+ concentration associated with PFS

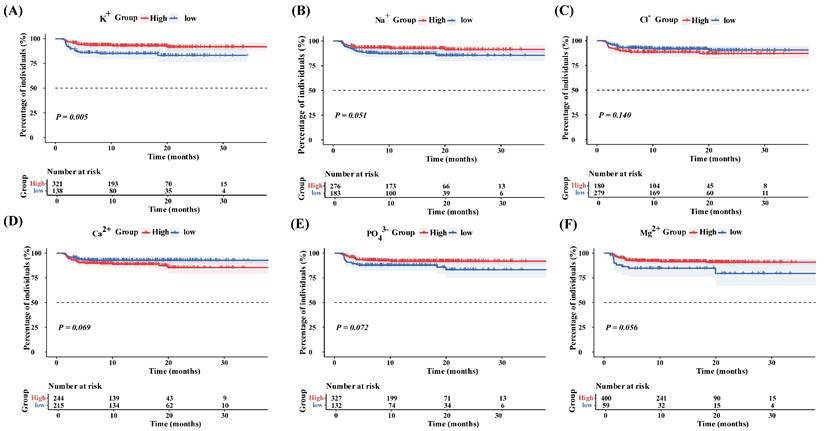

The optimal cut-off values for each ion concentration (K+, Na+, Cl-, Ca2+, PO43- and Mg2+) were obtained by using the surv_cutpoint() function in the survminer package of R 4.1.1 software (Table S1). The Kaplan - Meier curve showed that the survival probability was higher in the high K+ group than in the low K+ group. In contrast, no significant differences in survival were observed for Na+, Cl-, Ca2+, PO43- and Mg2+ (P > 0.05) (Figure 3). Univariable analysis revealed a significantly lower outcome risk in the high K+ group (HR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.24 -0.79, P = 0.006). multivariable analysis confirmed that a high K+ level was an independent prognostic factor for prolonged progression-free survival (HR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.28 -0.96, P = 0.036) (Table 3).

Univariable and Multivariable analyses of PFS (n = 459).

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (≥ 60 vs. < 60) | 0.90 (0.50 -1.64) | 0.741 | ||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.78 (0.35 -1.75) | 0.543 | ||

| ICIs treatment cycle | 0.89 (0.82 -0.95) | 0.001 | 0.87(0.80-0.93) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status (former/current vs. never) | 1.39 (0.62 -3.12) | 0.429 | ||

| Metastasis (yes vs. no) | 3.74 (1.66 -8.41) | 0.001 | 3.78 (1.64 -8.72) | 0.002 |

| No. of treatment line (≥ 2 vs. 1) | 2.94 (1.57 -5.50) | <0.001 | 2.23 (1.17 -4.23) | 0.015 |

| Preexisting diseases (yes vs. no) | 2.27 (1.05 -4.88) | 0.037 | 2.03 (0.89-4.62) | 0.091 |

| Histology (LUAD vs.non-LUAD) | 1.53 (0.84 -2.76) | 0.163 | ||

| K+ (high vs. low) | 0.43 (0.24 -0.79) | 0.006 | 0.52 (0.28 -0.96) | 0.036 |

Progression-free survival stratified by serum ion concentrations. (A) High vs. low potassium ions. (B) High vs. low sodium ions. (C) High vs. low chloride ions. (D) High vs. low calcium ions. (E) High vs. low phosphate ions. (F) High vs. low magnesium ions.

Discussion

Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have significantly advanced cancer treatment, the absence of reliable biomarkers for precise patient selection remains a major challenge [23, 24]. Investigating the relationship between immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and prognostic biomarkers may provide new insights. While multiple studies have confirmed a positive correlation between the occurrence of irAEs and improved prognosis in cancer patients [25-27], commonly shared biomarkers for both irAEs and prognosis remain scarce. In this study, we found that elevated potassium ion (K+) concentration was associated with higher objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR). Moreover, patients with higher K+ levels were more prone to developing irAEs and exhibited better prognoses.

As previously reported, factors such as advanced age, gender, and smoking history have been suggested to correlate with irAE development [28-30]. However, the present study did not identify significant associations between irAEs and demographic characteristics, tumor histology, or comorbidities, implying that immune-related factors may play a more dominant role in determining susceptibility to irAEs. Our findings align with earlier reports indicating that the incidence of irAEs is linked to PD-L1 expression, number of treatment cycles, and clinical outcomes such as ORR and DCR in ICI-treated patients [31-33].

The overall incidence of irAEs in our cohort was 82.4%, consistent with previously reported rates following ICI therapy [34]. Although the incidence of grade ≥ 3 irAEs is generally around 23% in literature, with most events being low-grade and self-limiting [35], our study observed a comparatively higher rate of severe (grade ≥3) irAEs. This discrepancy may be partly explained by a broader patient population, as prospective studies such as that by Fujimoto et al. have demonstrated that patients ineligible for clinical trials tend to experience higher incidences of grade ≥3 adverse events [36].

Mechanistically, potassium ions (K+) are essential for electrochemical regulation, cellular homeostasis, and metabolic signaling. Elevated extracellular K+ concentrations in the tumor microenvironment disrupt the intracellular K+ gradient, which in turn inhibits voltage-gated Kv1.3 channels and blocks the Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. These disruptions induce metabolic alterations and promote epigenetic modifications, ultimately leading to T-cell exhaustion [37-39]. Moreover, intratumoral high K+ regulates the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) toward an immunosuppressive phenotype via the inward rectifier K⁺ channel Kir2.1, and K⁺ released from necrotic tumor cells creates a vicious cycle that suppresses CD8⁺ T-cell function [40, 41]. Paradoxically, such potassium overload also directly restricts tumor growth by inducing tumor cell apoptosis and stabilizing G-quadruplex structures in the promoter regions of oncogenes such as c-Myc, thereby repressing their transcription and inhibiting cellular proliferation [42, 43]. Consequently, Elevated K+ serves as a biomarker of tumor cell death and systemic immune dysregulation, wherein released K+ and antigens prime T cells improving tumor control and prognosis while increasing irAE risk.

However, the study has some limitations, the retrospective design and single- center cohort resulted in limited generalizability of the results, and unmeasured confounders such as comorbid medications may interfere with electrolyte levels. Therefore, prospective studies are urgently needed to further validate causality and establish the reliability of K+ as a predictive tool.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of K+ monitoring in the management of ICI-treated patients. As a potential biomarker for irAEs and prognosis, K+ provides a theoretical basis for identifying patients at high risk of irAEs and optimizing monitoring protocols, which is expected to improve clinical outcomes in lung cancer immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary table.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (82173901), Major Project of Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Open competition, 2021JC0002), Hunan Province key research and development plan of China (2023SK2007), Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2024JJ8180, 2024JJ6292), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M733973), and Changsha Municipal Natural Science Foundation (kq2014208, kq2208408).

Author contributions

Z-Q Liu,Z Wang and J Chen designed and oversaw the study. C-W Liao and J Chen developed research methods. C-W Liao conducted software implementation, formal analysis, investigation, and data curation. J Chen, J-S Liu, L She, T Zou, Z Wang, Y Wang, and Z-Q Liu provided research resources. C-W Liao and Z Wang prepared the initial manuscript and conducted review/editing. C-W Liao created visual representations of the results. J Chen supervised the project and managed its administration. Z-Q Liu and J Chen obtained funding for the study. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data are available through Supplementary Materials or by request.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-49

2. Chhikara BS, Parang K. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: the trends projection analysis. Chem Biol Lett. 2023;10:451

3. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for the Treatment of Cancer: Clinical Impact and Mechanisms of Response and Resistance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2021;16:223-49

4. Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, Meza R, Kong CY, Cronin KA. et al. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:640-9

5. Postow MA, Longo DL, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:158-68

6. Khoja L, Day D, Wei-Wu Chen T, Siu LL, Hansen AR. Tumour- and class-specific patterns of immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2377-85

7. Haanen J, Obeid M, Spain L, Carbonnel F, Wang Y, Robert C. et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:1217-38

8. Wang DY, Ye F, Zhao SL, Johnson DB. Incidence of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis in solid tumor patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1344805

9. Ihrig A, Richter J, Grüllich C, Apostolidis L, Horak P, Villalobos M. et al. Patient expectations are better for immunotherapy than traditional chemotherapy for cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146:3189-98

10. Genova C, Dellepiane C, Carrega P, Sommariva S, Ferlazzo G, Pronzato P. et al. Therapeutic Implications of Tumor Microenvironment in Lung Cancer: Focus on Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Front Immunol. 2021;12:799455

11. Tan S, Day D, Nicholls SJ, Segelov E. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Oncology: Current Uses and Future Directions: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol. 2022;4:579-97

12. Tiwari A, Trivedi R, Lin SY. Tumor microenvironment: barrier or opportunity towards effective cancer therapy. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29(1):83

13. Pradeu T, Vivier E. The discontinuity theory of immunity. Sci Immunol. 2016;1:aag0479

14. Gao YX, Liu SS, Huang YF, Li F, Zhang Y. Regulation of anti-tumor immunity by metal ion in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1379365

15. Shen FY, Fang Y, Wu YJ, Zhou M, Shen JF, Fan XQ. Metal ions and nanometallic materials in antitumor immunity: Function, application, and perspective. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023;21(1):20

16. Boedtkjer E. Ion Channels, Transporters, and Sensors Interact with the Acidic Tumor Microenvironment to Modify Cancer Progression. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;182:39-84

17. Eil R, Vodnala SK, Clever D, Klebanoff CA, Sukumar M, Pan J. et al. Ionic immune suppression within the tumour microenvironment limits T cell effector function. Nature. 2016;537(7621):539-543

18. Yin ZP, Bai L, Li W, Zeng TL, Tian HM, Cui J. Targeting T cell metabolism in the tumor microenvironment: an anti-cancer therapeutic strategy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):403

19. He Q, Jiang X, Zhou X, Weng J. Targeting cancers through TCR-peptide/MHC interactions. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):139

20. Valpione S, Mundra PA, Galvani E, Campana LG, Lorigan P, De Rosa F. et al. The T cell receptor repertoire of tumor infiltrating T cells is predictive and prognostic for cancer survival. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4098

21. Ginefra P, Hope HC, Spagna M, Zecchillo A, Vannini N. Ionic Regulation of T-Cell Function and Anti-Tumour Immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(24):13668

22. Wang C, Zhang R, Wei X, Lv M, Jiang Z. Metalloimmunology: The metal ion-controlled immunity. Adv Immunol. 2020;145:187-241

23. Gang X, Yan J, Li X, Shi S, Xu L, Liu R. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors rechallenge in non-small cell lung cancer: Current evidence and future directions. Cancer Lett. 2024;604:217241

24. Lindberg A, Muhl L, Yu H, Hellberg L, Artursson R, Friedrich J. et al. In Situ Detection of Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 and Programmed Death Ligand 1 Interactions as a Functional Predictor for Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2025;20:625-40

25. Safa H, Abu Rous F, Belani N, Borghaei H, Gadgeel S, Halmos B. Emerging Biomarkers in Immune Oncology to Guide Lung Cancer Management. Target Oncol. 2023;18:25-49

26. Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Nishio M, Mok TSK, Reck M. et al. Association of Immune-Related Adverse Events With Efficacy of Atezolizumab in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Pooled Analyses of the Phase 3 IMpower130, IMpower132, and IMpower150 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9:527-35

27. Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, Nowecki Z, Im SA, Yusof MM. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1817-28

28. Chen C, Zhang CY, Jin ZY, Wu B, Xu T. Sex differences in immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors: data mining of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44:689-97

29. Chen C, Zhang CY, Wu B, Xu T. Immune-related adverse events in older adults: Data mining of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. J Geriatr Oncol. 2022;13:1017-22

30. Hata H, Matsumura C, Chisaki Y, Nishioka K, Tokuda M, Miyagi K. et al. A Retrospective Cohort Study of Multiple Immune-Related Adverse Events and Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With Cancer Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Control. 2022;29:10732748221130576

31. Cook S, Samuel V, Meyers DE, Stukalin I, Litt I, Sangha R. et al. Immune-Related Adverse Events and Survival Among Patients With Metastatic NSCLC Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2352302

32. Watson AS, Goutam S, Stukalin I, Ewanchuk BW, Sander M, Meyers DE. et al. Association of Immune-Related Adverse Events, Hospitalization, and Therapy Resumption With Survival Among Patients With Metastatic Melanoma Receiving Single-Agent or Combination Immunotherapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2245596

33. Serino M, Freitas C, Martins M, Ferreira P, Cardoso C, Veiga F. et al. Predictors of immune-related adverse events and outcomes in patients with NSCLC treated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Pulmonology. 2024;30:352-61

34. Robert C, Carlino MS, McNeil C, Ribas A, Grob JJ, Schachter J. et al. Seven-Year Follow-Up of the Phase III KEYNOTE-006 Study: Pembrolizumab Versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:3998-4006

35. Martini DJ, Goyal S, Liu Y, Evans ST, Olsen TA, Case K. et al. Immune-Related Adverse Events as Clinical Biomarkers in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Oncologist. 2021;26(10):e1742-e1750

36. Fujimoto D, Morimoto T, Tamiya M, Hata A, Matsumoto H, Nakamura A. et al. Outcomes of Chemoimmunotherapy Among Patients With Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer According to Potential Clinical Trial Eligibility. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e230698

37. Yang ZL, Shao XL, Wu YT, Roy A, Garcia E, Farrell A. et al. Decoding Potassium Homeostasis in Cancer Metastasis and Drug Resistance: Insights from a Highly Selective DNAzyme-Based Intracellular K+ Sensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147:18074-87

38. Vodnala SK, Eil R, Kishton RJ, Sukumar M, Yamamoto TN, Ha NH. et al. T cell stemness and dysfunction in tumors are triggered by a common mechanism. Science. 2019;363(6434):eaau0135

39. Feske S, Wulff H, Skolnik EY. Ion Channels in Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:291-353

40. Chen S, Cui WY, Chi ZX, Xiao Q, Hu TY, Ye QZ. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages are shaped by intratumoral high potassium via Kir2.1. Cell Metab. 2022;34(11):1843-1859.e11

41. Puttalingaiah RT, Dean MJ, Zheng LQ, Philbrook P, Wyczechowska D, Kayes T. et al. Excess Potassium Promotes Autophagy to Maintain the Immunosuppressive Capacity of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Independent of Arginase 1. Cells. 2024;13(20):1736

42. Wang YZ, Wang HG, Ding W, Zhao XF, Li YD, Liu CL. Effect of THz Waves of Different Orientations on K+ Permeation Efficiency in the KcsA Channel. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;25(1):429

43. Tateishi-Karimata H, Kawauchi K, Sugimoto N. Destabilization of DNA G-Quadruplexes by Chemical Environment Changes during Tumor Progression Facilitates Transcription. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(2):642-651

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Professor Zhao-Qian Liu, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Hunan Key Laboratory of Pharmacogenetics, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008; P. R. China. Tel: +86 731 84805380, Fax: +86 731 82354476, E-mail: zqliuedu.cn. OR Zhan Wang, Lung Cancer and Gastrointestinal Unit, Department of Medical Oncology, Hunan Cancer Hospital/The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University, Changsha 410031, P. R. China. E-mail: wan0916wancom.

Corresponding authors: Professor Zhao-Qian Liu, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Hunan Key Laboratory of Pharmacogenetics, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008; P. R. China. Tel: +86 731 84805380, Fax: +86 731 82354476, E-mail: zqliuedu.cn. OR Zhan Wang, Lung Cancer and Gastrointestinal Unit, Department of Medical Oncology, Hunan Cancer Hospital/The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University, Changsha 410031, P. R. China. E-mail: wan0916wancom.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact