Impact Factor

ISSN: 1837-9664

J Cancer 2026; 17(2):316-337. doi:10.7150/jca.126708 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Single-cell and transcriptomic profiling reveal stemness-driven immune evasion in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) associated lung cancer

1. Division of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung 80756, Taiwan.

2. Nursing Department, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, National Defense Medical University, Kaohsiung 80284, Taiwan.

3. College of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 80708, Taiwan.

4. Medical Laboratory, Medical Education and Research Center, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, National Defense Medical University, Kaohsiung 80284, Taiwan.

5. Division of Experimental Surgery Center, Department of Surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

6. Institute of Medical Science and Technology, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung 80424, Taiwan.

7. Department of Medical Imaging, Chi-Mei Medical Center, Tainan 710402, Taiwan.

8. Department of Health and Nutrition, Chia Nan University of Pharmacy and Science, Tainan 71710, Taiwan.

9. School of Medicine, College of Medicine, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung 80424, Taiwan.

10. PhD Program for Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

11. Graduate Institute of Cancer Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

12. PhD Program for Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

13. Faculty of Applied Sciences and Biotechnology, Shoolini University of Biotechnology and Management Sciences, Himachal Pradesh, 173229, India.

14. Department of Biotechnology, Mother Teresa Women's University, Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu, 624101, India.

15. Computer Engineering with specialization in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, Presidency University, Yelahanka, Bengaluru 560064 India.

16. Faculty of Pharmacy, Van Lang University, 69/68 Dang Thuy Tram Street, Ward 13, Binh Thanh District, Ho Chi Minh City 70000, Vietnam.

17. Center for Regenerative Medicine, University of South Florida Health Heart Institute, Tampa, Florida 33602, USA.

18. Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Morsani School of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33602, USA.

19. Department of Otolaryngology, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, National Defense Medical University, Kaohsiung 80284, Taiwan.

20. Department of Otolaryngology, National Defense Medical University, Taipei 11490, Taiwan.

21. Department of Surgery, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, National Defense Medical University, Kaohsiung 80284, Taiwan.

† Equal contributors.

Received 2025-10-14; Accepted 2025-12-12; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

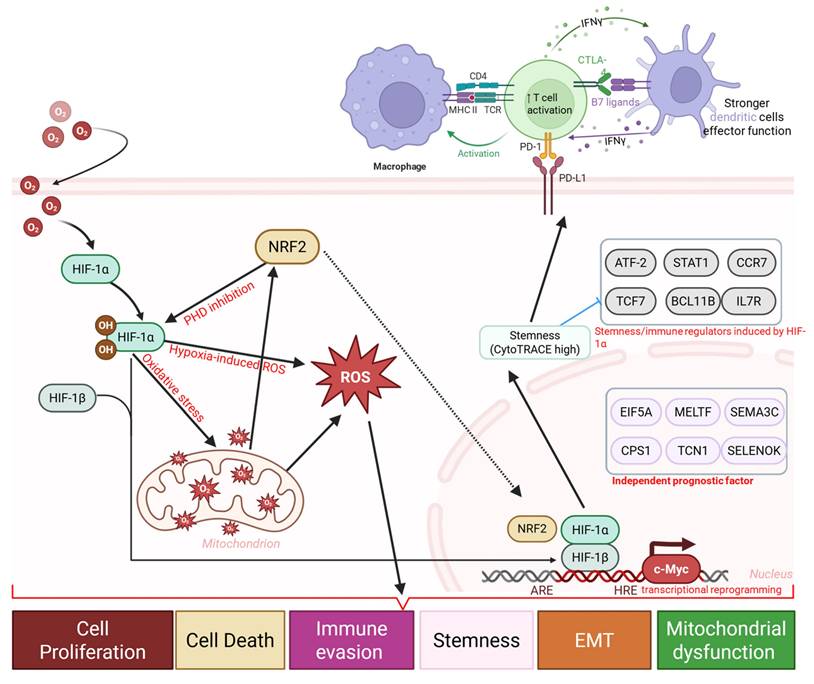

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by recurrent intermittent hypoxia (IH) and has been increasingly associated with lung cancer incidence and mortality. However, how IH-related biological programs relate to immune remodeling, stemness-associated phenotypes, and therapeutic resistance in lung cancer remains incompletely understood. We integrated single-cell RNA sequencing data from IH-exposed murine lung tissues (GSE301350) with bulk transcriptomic datasets from TCGA-LUAD and GSE31210 to examine hypoxia-associated cellular and transcriptional patterns. Stemness was quantified using CytoTRACE and transcriptome-based stemness scoring, and its associations with immune infiltration, immune checkpoint expression, TIDE scores, predicted drug sensitivity, and immunotherapy response were evaluated. A stemness-based prognostic model was constructed using LASSO Cox regression and validated in independent cohorts. Single-cell analysis revealed marked immune remodeling under intermittent hypoxia (IH), including expansion of effector T cells, and monocytes/macrophages, populations alongside reduced B cells and dendritic cells. In human LUAD cohorts, stemness-high tumors were associated with mitochondrial and metabolic stress-related transcriptional programs, and increased expression of immune checkpoint genes (PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA4, LAG3). Elevated stemness scores correlated with higher TIDE scores, poorer overall survival, and reduced predicted responsiveness to immunotherapy. LASSO modeling identified a six-gene stemness signature (EIF5A, MELTF, SEMA3C, CPS1, TCN1, SELENOK), that consistently stratified patients into high- and low-risk groups across TCGA and GSE31210 cohorts. Multivariate Cox regression confirmed the risk score as an independent prognostic factor. Drug sensitivity analyses further suggested that stemness-high tumors may exhibit increased susceptibility to selected kinase inhibitors (Dasatinib, A-770041) and metabolic modulators (Phenformin, Salubrinal). OSA-associated IH is linked to stemness-associated transcriptional plasticity, immune suppression, and adverse clinical outcomes in lung cancer. The identified stemness-based gene signature provides a robust prognostic biomarker and highlights potential therapeutic vulnerabilities, supporting integrative strategies that combine stemness and immune -targeted approaches with immunotherapy in OSA-associated lung cancer.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, intermittent hypoxia, lung cancer, stemness, immune evasion, prognostic model, immunotherapy

1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a highly prevalent sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of upper airway collapse and intermittent hypoxia (IH) [1-3]. Epidemiological studies have established OSA as a risk factor for a broad spectrum of cardiometabolic diseases, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and atherosclerosis, as well as respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary hypertension [4-6]. More recently, increasing attention has been directed toward the potential link between OSA and cancer. Clinical cohort studies and meta-analyses suggest that OSA severity, particularly nocturnal hypoxemia, correlates with higher incidence and mortality of lung cancer, yet the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood [7-10]. Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounting for approximately 85% of all cases [11, 12]. Despite advances in immunotherapy and targeted therapy, the prognosis of advanced NSCLC remains unsatisfactory, highlighting the urgent need for improved biomarkers and mechanistic insights [13, 14]. Hypoxia is a well-recognized hallmark of the tumor microenvironment (TME), promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis, immune suppression, and therapeutic resistance [15, 16]. Given that OSA subjects experience recurrent systemic and tissue-level hypoxic stress, intermittent hypoxia may act as a “priming factor” that accelerates lung tumorigenesis and shapes the TME toward malignancy [10, 17]. However, most prior studies have focused on bulk transcriptomic or animal models, leaving the cell-type-specific effects of IH largely unexplored [18, 19].

Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) provide unprecedented opportunities to dissect the heterogeneity of lung tissues under OSA-associated IH conditions [20, 21]. By resolving cell-type-specific transcriptional programs, scRNA-seq allows the identification of altered immune infiltration, stemness-associated reprogramming, and immunometabolic shifts that bulk analyses cannot capture [22]. In particular, cellular stemness, the degree to which tumor and immune cells adopt progenitor-like transcriptional states has emerged as a critical determinant of tumor progression, immune evasion, and therapy response. Computational approaches such as CytoTRACE and integrative stemness scoring now enable quantification of stemness at both single-cell and bulk-tumor levels, facilitating the construction of prognostic models with direct clinical applicability [23-25]. Candidate genes and pathways highlighted in this study were prioritized using a quantitative, multi-criteria framework, incorporating stemness association, statistical robustness, cross-dataset consistency, and relevance to hypoxia and immune regulation, rather than isolated statistical significance.

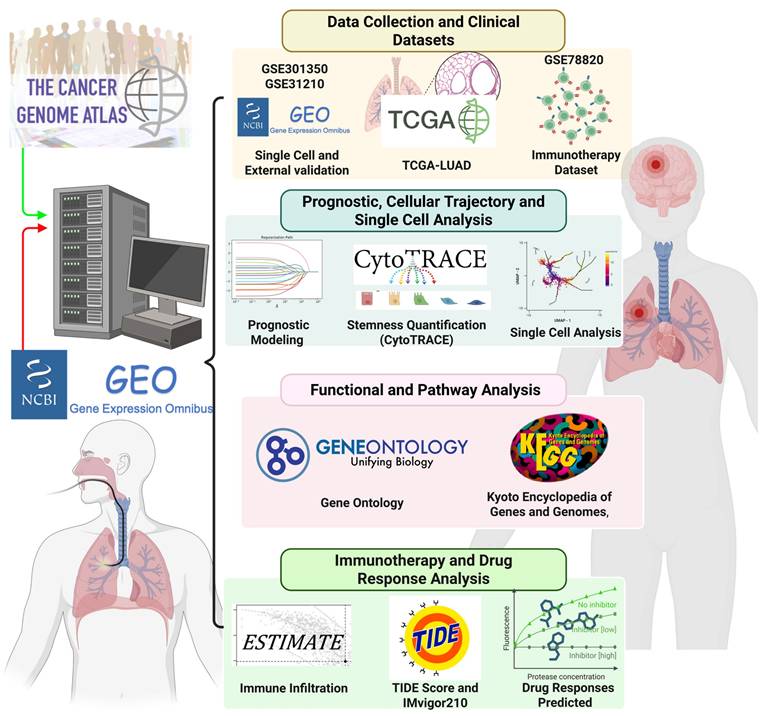

In this study, we integrated scRNA-seq data from OSA-associated IH lung models (GSE301350) with bulk transcriptomic datasets (TCGA-LUAD and external validation cohorts) to investigate the role of stemness in OSA-related lung cancer. Through comprehensive analyses, including immune infiltration deconvolution, checkpoint gene profiling, TIDE assessment, and drug sensitivity prediction, we aimed to delineate the molecular mechanisms linking OSA-driven hypoxia to tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Furthermore, we developed and validated a stemness-based prognostic model using LASSO Cox regression, demonstrating its independent predictive value and translational potential in guiding personalized therapy (Figure 1) [26, 27]. Our work provides novel insights into how OSA-associated intermittent hypoxia may reprograms the lung microenvironment through stemness-associated and immune-related mechanisms, thereby enhancing cancer susceptibility and progression. These findings not only improve mechanistic understanding of the OSA-cancer link but also identify actionable biomarkers and therapeutic vulnerabilities that could inform future precision oncology strategies for patients with OSA-related lung cancer. We emphasize that this study does not assume direct molecular equivalence between murine intermittent hypoxia models and human lung adenocarcinoma. Instead, the murine single-cell RNA-seq data were used as a mechanistic discovery framework to characterize hypoxia-responsive cellular states and immune remodeling, while independent human LUAD transcriptomic cohorts were leveraged to assess the clinical relevance of stemness-associated transcriptional programs. This integrative strategy allows hypoxia-linked biological themes identified in experimental models to be contextualized and validated at the prognostic and immunological level in human disease, without implying direct cross-species gene-level concordance.

Study workflow and integrative analyses for OSA-associated lung cancer. Study workflow and integrative analyses for OSA-associated lung cancer. Overview of the computational and experimental strategy. Multi-omics data (TCGA-LUAD, GSE301350, GSE31210, GSE78820) and single-cell RNA-seq datasets were integrated to quantify stemness (CytoTRACE, stemness scores), characterize immune infiltration (CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE), and assess functional pathways (GO ontology, and KEGG,). Prognostic modeling was performed using LASSO Cox regression and validated in independent cohorts. Immunotherapy response was evaluated using TIDE and IMvigor210 datasets, and drug sensitivity was predicted using GDSC data. The pipeline highlights the integration of stemness quantification, immune landscape profiling, and therapeutic prediction in OSA-associated lung cancer.

2. Methods

2.1 Data acquisition and preprocessing

The single-cell RNA-seq dataset GSE301350, comprising lung tissues from mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia (IH) or normoxia (Nx), was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Raw count matrices were processed using the Seurat R package (v4.4.1). Cells with fewer than 200 detected genes, more than 5,000 detected genes, or > 10% mitochondrial gene content were excluded. Gene expression matrices were normalized and log-transformed, followed by principal component analysis (PCA) and batch effect correction using Harmony [28-30]. Dimensionality reduction was performed using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP).

2.2 Cell-type annotation and marker gene identification

Cell clustering was performed with the Seurat “FindClusters” function at a resolution of 0.5-1.2. Marker genes for each cluster were identified by the “FindMarkers” function using Wilcoxon rank-sum testing with thresholds of |log2 fold change| > 0.25 and adjusted p < 0.05. Cell types were annotated based on canonical lineage markers, cross-referenced with the CellMarker database and published literature [31-35].

2.3 Stemness estimation and functional enrichment

Cellular differentiation potential at the single-cell level was inferred using CytoTRACE, with higher scores indicating greater transcriptional similarity to progenitor-like states. At the bulk-transcriptomic level stemness scores for TCGA-LUAD and GSE31210 samples were calculated by summing the weighted expression of stemness-associated product of gene using pre-defined coefficients. Functional enrichment analyses were conducted to identify pathway-associated transcriptional programs linked to stemness and hypoxia-related phenotypes. Gene Ontology biological process (GO-BP) and KEGG pathway gene sets were analyzed using the clusterProfiler package (v4.10.0). Enrichment results were interpreted as coordinated gene expression patterns rather than direct evidence of biological pathway activation or mechanistic causality. Statistical significance was assessed using adjusted p-values, with pathways meeting an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.25 considered significantly enriched [36-41].

2.4 Survival analysis and prognostic model construction

Differentially expressed genes between high- and low-stemness groups were identified using limma (v3.54.2). Genes associated with overall survival were first screened by univariate Cox regression (p < 0.05). To minimize overfitting, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression was applied using the glmnet package with 10-fold cross-validation. A multigene prognostic signature was established, and a risk score was calculated as the sum of each gene's expression weighted by its regression coefficient. Patients were stratified into high- and low-risk groups using the median risk score. Model performance was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (timeROC package).

2.5 Independent validation

The prognostic model was validated in the GSE31210 dataset. Risk scores were computed using the same formula derived from TCGA-LUAD. Kaplan-Meier and ROC analyses were performed to assess predictive accuracy. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses incorporating age, sex, TNM stage, and clinical stage were conducted to determine independent prognostic value [42-46].

2.6 Immune infiltration and checkpoint analysis

Immune cell proportions were estimated using CIBERSORT with 22 leukocyte subsets and 1,000 permutations. Stromal and immune scores were calculated using the ESTIMATE algorithm. Immune checkpoint expression was compared between stemness-defined groups using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Associations between stemness score and immune checkpoint expression were assessed using Pearson correlation.

2.7 TIDE and immunotherapy response prediction

The Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) algorithm was used to estimate tumor immune escape potential. Associations between TIDE and stemness scores were evaluated using Spearman correlation. External immunotherapy cohorts with clinical response data were used to assess whether stemness risk groups predicted treatment outcomes, with patients categorized as responders (complete response [CR] or partial response [PR]) or non-responders (stable disease [SD] or progressive disease [PD]) [47-51].

2.8 Drug sensitivity analysis

Drug response prediction was performed using the oncoPredict package. Estimated half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for compounds in the GDSC database were compared between high- and low-risk groups using Wilcoxon testing. Candidate drugs were selected based on consistent differences across cohorts and biological relevance to stemness-related pathways [52-56].

2.9 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R (v4.4.1). Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Student's t-test, as appropriate. Correlations were assessed by Pearson or Spearman coefficients. Survival differences were determined using the log-rank test. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified [57-61].

3. Results

3.1 Differential gene expression and LASSO modeling identify stemness-associated prognostic signatures in OSA-related lung cancer

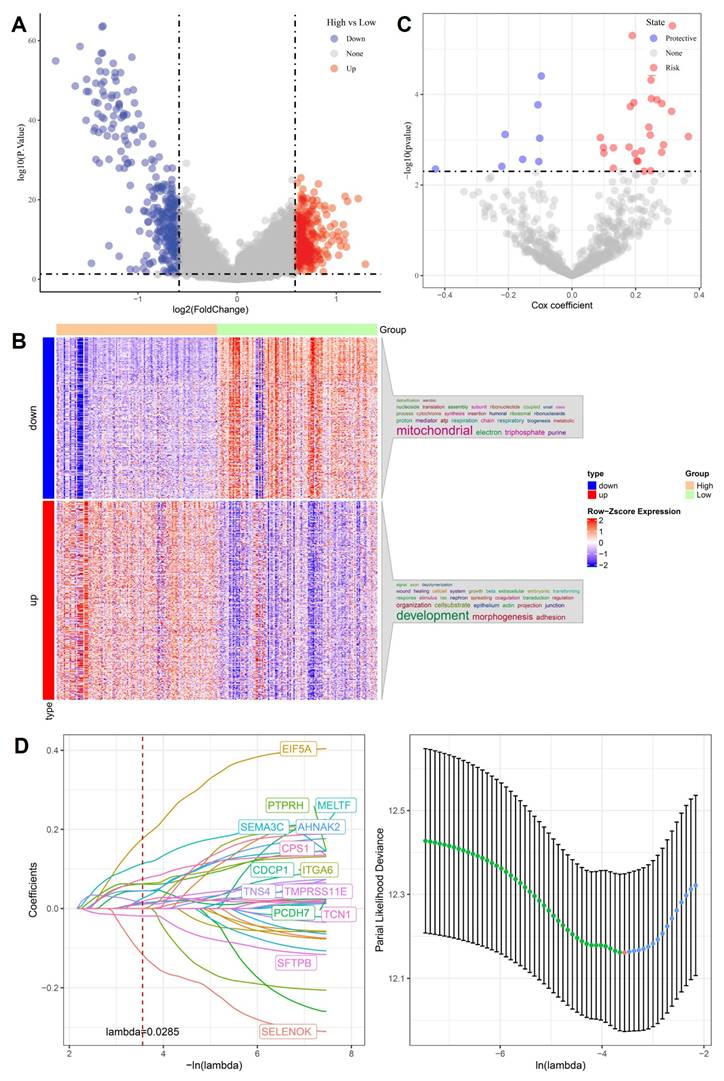

To uncover molecular mediators of stemness-driven progression in OSA-related lung cancer, we first compared transcriptomes between high- and low-stemness tumors. Volcano plot analysis revealed hundreds of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with significant upregulation of developmental regulators and suppression of mitochondrial/respiratory chain genes (Figure 2A). Heatmap clustering confirmed that stemness-high tumors were characterized by enhanced expression of adhesion, morphogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling genes, while low-stemness tumors were enriched in oxidative phosphorylation and electron transport pathways (Figure 2B). We next performed univariate Cox regression to assess the prognostic impact of DEGs. Several genes, including EIF5A and MELTF, emerged as high-risk factors, while others, such as SFTPB and SELENOK, displayed protective associations (Figure 2C). This dichotomy highlights the complex transcriptional landscape in which stemness-high tumors harness developmental pathways to enhance aggressiveness while silencing mitochondrial guardians that maintain cellular homeostasis. To refine these observations into a clinically actionable model, we applied LASSO Cox regression. Cross-validation identified a parsimonious panel of 15 genes with optimal prognostic value (Figure 2D). This stemness-associated signature integrates developmental drivers such as PTPRH, AHNAK2, PCDH7, metabolic regulators CPS1, SFTPB, and hypoxia-responsive factors such as TCN1, TMPRSS11E, reflecting the multifaceted nature of OSA-induced tumor evolution. Importantly, the predictive capacity of this model provides a robust framework for stratifying patients by risk, linking stemness biology to clinical outcomes. Collectively, these analyses establish a mechanistic bridge between OSA-related hypoxia, stemness reprogramming, and clinical prognosis. By pinpointing gene signatures tied to both mitochondrial dysfunction and developmental activation, the LASSO-derived model offers not only prognostic insights but also potential therapeutic targets to disrupt the stemness-hypoxia-immune axis in lung cancer.

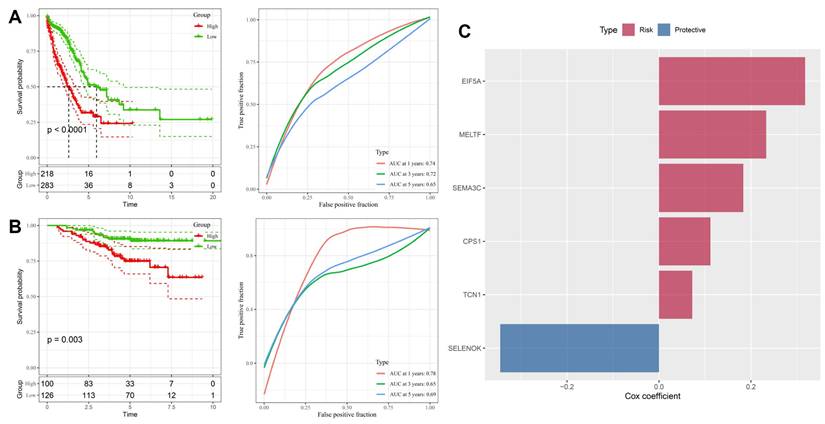

3.2 Stemness-associated gene signature robustly predicts survival across training and validation cohorts

To validate the prognostic value of the stemness-associated signature derived from LASSO analysis, we first applied it to the TCGA-LUAD training dataset. Patients stratified into high- and low-risk groups demonstrated markedly divergent outcomes, with the high-risk group exhibiting significantly worse overall survival (p < 0.0001, Figure 3A). Time-dependent ROC analysis confirmed good predictive performance, with AUC values of 0.74, 0.72, and 0.65 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival, respectively, indicating that the model retains both short- and medium-term prognostic utility. Independent validation in the GSE31210 cohort yielded consistent results, with high-risk patients again showing significantly poorer survival (p = 0.003, Figure 3B). Predictive accuracy was comparable, with AUC values of 0.78, 0.65, and 0.69 across 1-, 3-, and 5-year timepoints, demonstrating the robustness and generalizability of the model across different patient populations. Examination of gene-specific Cox coefficients highlighted both risk and protective components of the model (Figure 3C). EIF5A, MELTF, SEMA3C, CPS1, and TCN1 were identified as risk-promoting genes, each associated with adverse prognosis and consistent with their roles in proliferation, metabolic rewiring, and hypoxia responses. In contrast, SELENOK emerged as a protective factor, potentially linked to its role in antioxidant defense and maintenance of cellular homeostasis. Together, these results confirm that the stemness-driven gene signature derived from OSA-related hypoxia biology provides a reliable and externally validated prognostic model. By integrating developmental regulators, metabolic genes, and hypoxia-responsive factors, the model captures the multifaceted influence of intermittent hypoxia on lung tumor evolution. Importantly, the reproducibility of its predictive power across TCGA and GSE31210 underscores its translational potential as a clinical tool for patient risk stratification and treatment planning.

Identification of stemness-associated prognostic genes. (A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (high vs. low stemness groups). (B) Heatmap of up- and downregulated genes, enriched in mitochondrial and developmental pathways. (C) Univariate Cox analysis highlighting risk and protective genes. (D) LASSO regression identifying optimal prognostic gene set with cross-validation curve.

Prognostic performance of the stemness-based risk model. (A) Kaplan-Meier and ROC analysis in TCGA-LUAD training cohort, showing worse survival in high-risk patients and good predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.74, 0.72, 0.65 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival). (B) Validation in GSE31210 cohort confirmed survival discrimination and predictive performance (AUC = 0.78, 0.65, 0.69). (C) Cox coefficients of selected genes in the final model, with EIF5A, MELTF, SEMA3C, CPS1, and TCN1 as risk factors, and SELENOK as protective.

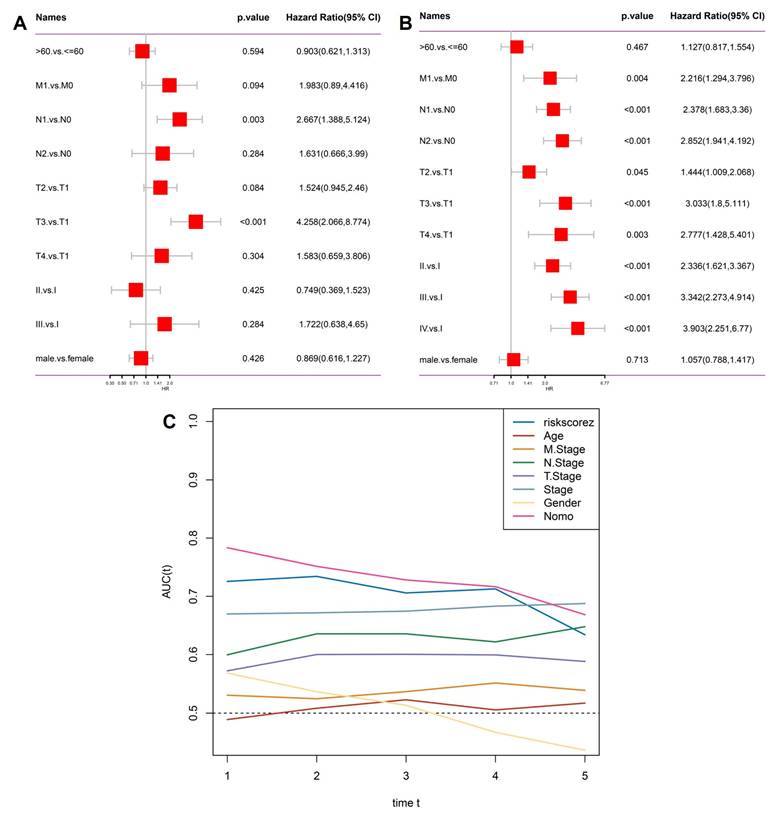

3.3 Stemness-based risk score serves as an independent prognostic factor in OSA-related lung cancer

To test whether the stemness-derived risk score could serve as an independent prognostic factor, we performed multivariate Cox regression analysis incorporating clinicopathological features (Figure 4A). The risk score remained significantly associated with overall survival even after adjustment for age, sex, and TNM stage, confirming its independence from traditional clinical parameters. Subsequently, we extracted only the significant predictors to construct a refined model (Figure 4B). In this reduced analysis, the stemness risk score, together with N stage and T stage, consistently emerged as robust prognostic indicators, whereas variables such as age and gender did not reach statistical significance. Time-dependent ROC analysis further demonstrated that the stemness risk score outperformed conventional variables in predictive accuracy, maintaining AUC values above 0.70 across multiple timepoints (Figure 4C). This stability underscores the clinical value of the model as a reliable risk stratification tool. Together, these findings establish the OSA-associated stemness signature as an independent prognostic factor with superior predictive performance compared to traditional staging systems, thereby providing a molecularly informed framework for patient management.

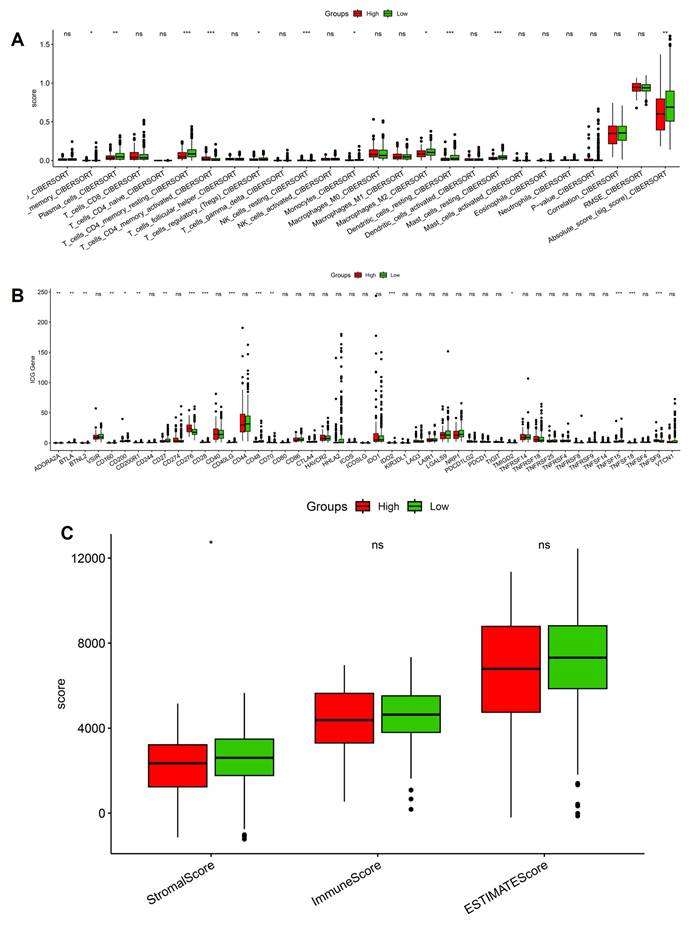

3.4 Stemness-high tumors display altered immune infiltration, checkpoint expression, and stromal remodeling

We next investigated the immune and stromal correlates of stemness by integrating CIBERSORT, checkpoint profiling, and ESTIMATE analysis. CIBERSORT deconvolution revealed significant enrichment of immunoregulatory populations in stemness-high tumors, including activated CD4⁺ T cells, regulatory T cells, and M2-polarized macrophages, whereas low-stemness tumors displayed relatively higher fractions of naïve B cells and resting dendritic cells (Figure 5A). These shifts suggest that stemness programs not only promote effector activation but also skew the immune milieu toward an immunosuppressive phenotype dominated by Tregs and M2 macrophages. Consistent with this observation, checkpoint expression analysis demonstrated broadly elevated levels of inhibitory molecules in the stemness-high group, including PDCD1 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1), CTLA4, and LAG3 (Figure 5B). The coordinated upregulation of these checkpoints implies that stemness-driven tumors rely on multiple redundant inhibitory pathways to dampen T-cell activation and evade immune destruction. Interestingly, some costimulatory ligands were also variably increased, reflecting a mixed signaling environment that may initially activate but ultimately exhaust T-cell responses. ESTIMATE analysis further highlighted that stemness-high tumors harbored significantly higher stromal scores, while immune and composite scores did not differ markedly between groups (Figure 5C). This pattern suggests that stemness not only influences immune cell infiltration but also enhances stromal remodeling, potentially reinforcing physical and metabolic barriers to immune clearance. Notably, the immune infiltration patterns, checkpoint activation, and stromal remodeling observed in stemness-high human LUAD tumors are consistent with hypoxia-driven immune remodeling identified in the murine intermittent hypoxia model, supporting a coherent functional link between hypoxic stress, immune dysfunction, and tumor progression. Together, these data establish that OSA-associated stemness is intricately linked with an immunosuppressive and stromal-enriched tumor microenvironment. By coupling regulatory immune infiltration, checkpoint upregulation, and stromal expansion, stemness programs generate a tumor ecosystem optimized for immune escape and disease progression.

Independent prognostic evaluation of the stemness signature. (A) Multivariate Cox regression including clinical variables (age, gender, T stage, N stage, M stage, overall stage) and risk score. (B) Significant factors from Cox regression, highlighting stemness risk score alongside T stage and N stage as independent predictors. (C) Time-dependent AUC curves showing the predictive accuracy of the risk score compared with conventional clinical parameters.

Immune landscape differences between high- and low-stemness groups. (A) CIBERSORT-based immune cell infiltration analysis showing altered abundance of T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and overall immune scores. (B) Expression of immune checkpoint genes compared between high- and low-stemness tumors. (C) Summary of stemness-immune associations.

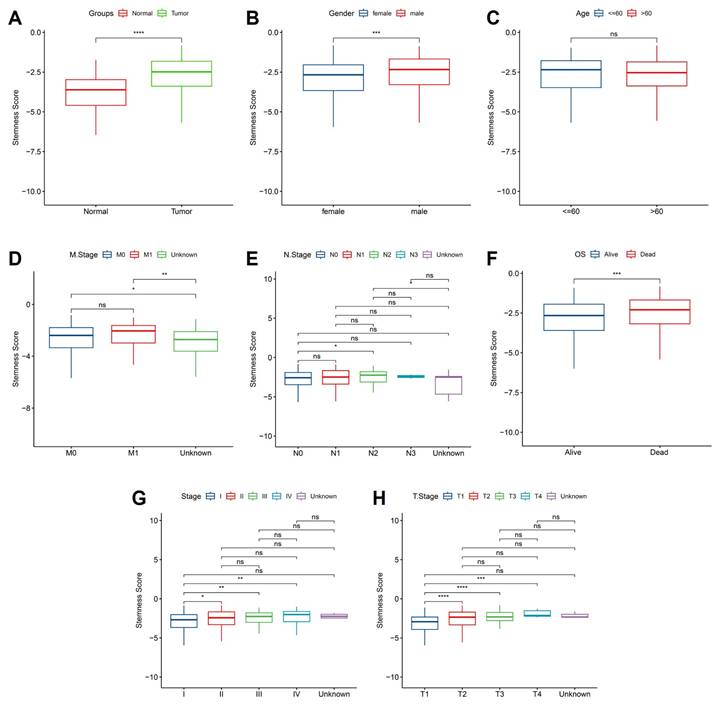

3.5 Stemness scores are elevated in tumors and associated with advanced clinical features in OSA-related lung cancer

To further elucidate the clinical relevance of hypoxia-associated stemness programs, we examined stemness scores across patient subgroups stratified by clinicopathological features. Tumor tissues exhibited significantly elevated stemness compared with matched normal samples (Figure 6A), reinforcing the concept that intermittent hypoxia and OSA-driven microenvironmental stress favor acquisition of progenitor-like traits. This elevation was particularly evident in male patients (Figure 6B), suggesting sex-related differences in hypoxia response pathways, potentially mediated by hormonal or immunological factors. In contrast, patient age had no significant impact on stemness distribution (Figure 6C), highlighting that hypoxia-induced stemness remodeling is independent of chronological aging. Metastatic disease status was tightly linked to stemness reprogramming: patients with distant metastasis (M1) harbored significantly higher stemness scores than non-metastatic cases (M0) (Figure 6D). Interestingly, lymph node involvement (N stage) alone did not correlate strongly with stemness (Figure 6E), suggesting that systemic dissemination rather than regional spread is more tightly governed by stemness-driven biology. Importantly, survival analysis demonstrated that elevated stemness scores predicted significantly worse overall survival (Figure 6F), underscoring its prognostic utility. When stratified by pathological stage, stemness scores exhibited a progressive rise with advancing tumor stage (Figure 5G), with marked increases from stage I-II to III-IV, implicating stemness as a driver of aggressive disease evolution. Similarly, analysis of primary tumor burden (T stage) revealed a stepwise elevation in stemness from T1 to T3 (Figure 6H), consistent with its role in sustaining proliferation, therapy resistance, and local invasiveness. Together, these findings provide compelling evidence that hypoxia-associated stemness, initially identified in the single-cell analyses, translates into clinically measurable signals that track with tumor aggressiveness, metastatic spread, and poor survival outcomes. This strongly supports the hypothesis that OSA-mediated intermittent hypoxia not only remodels immune and epithelial compartments but also accelerates malignant progression through stemness-driven mechanisms. Targeting stemness-associated vulnerabilities may therefore represent a promising therapeutic strategy in OSA-related lung cancer.

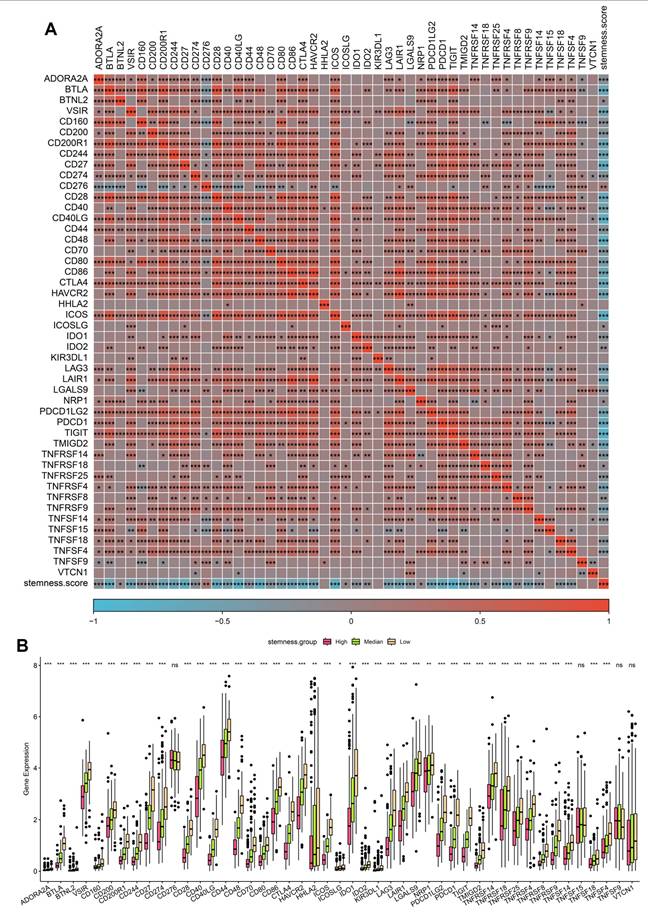

3.6 Stemness enrichment is associated with immune checkpoint activation in OSA-related lung cancer

Given the prognostic impact of stemness, we next examined its interplay with immune checkpoint expression, a central determinant of tumor immune evasion and immunotherapy responsiveness. Correlation heatmap analysis revealed that high stemness scores were strongly associated with increased expression of classical immune checkpoints, including PDCD1 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1), CTLA4, LAG3, and TIGIT, as well as costimulatory ligands such as CD80/CD86 (Figure 7A). These findings suggest that stemness-high tumors adopt a transcriptional program that converges on immune checkpoint activation, enabling them to suppress T-cell effector responses and evade immune surveillance. Boxplot comparisons further demonstrated that tumors in the high-stemness group exhibited significantly elevated expression of most inhibitory checkpoint genes compared with medium- and low-stemness groups (Figure 7B). Notably, PD-1/PD-L1, CTLA4, and LAG3 showed the most pronounced differences, indicating that stemness-enriched tumors may be particularly dependent on checkpoint-mediated immunosuppression. In contrast, only a limited subset of checkpoint molecules displayed no significant differences across stemness strata, highlighting the specificity of this association. These findings underscore a critical mechanistic link: intermittent hypoxia in OSA may foster stemness programs that not only drive tumor aggressiveness but also co-opt immune checkpoint pathways to facilitate immune evasion. Clinically, this dual effect provides a rationale for stratifying OSA-related lung cancer patients by stemness score to predict immunotherapy response. Patients with high stemness tumors may derive greater benefit from checkpoint inhibitor therapies.

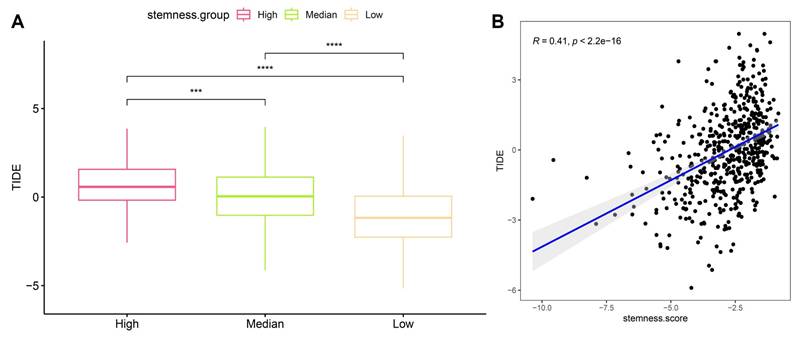

3.7 High stemness predicts stronger immune evasion potential by TIDE in OSA-related lung cancer

To evaluate whether stemness signatures influence tumor immune escape, we integrated Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) analysis with stemness stratification. Tumors classified as high-stemness exhibited markedly elevated TIDE scores compared to medium- and low-stemness groups (Figure 8A), indicating enhanced likelihood of immune evasion. This trend persisted across independent comparisons, underscoring the robustness of the association. Linear correlation analysis further confirmed a significant positive relationship between stemness score and TIDE value (R = 0.41, p < 2.2e-16) (Figure 8B), suggesting that stemness-enriched tumors consistently harbor stronger immunosuppressive potential. Mechanistically, the link between stemness and TIDE likely reflects synergistic interactions between progenitor-like transcriptional states, mitochondrial stress programs, and checkpoint activation identified before. High-stemness tumors appear to adopt a metabolic and transcriptional profile that not only promotes self-renewal and resistance to differentiation but also fosters an immune-excluded microenvironment, thereby evading cytotoxic T-cell surveillance. These dual features may explain why OSA-related hypoxia accelerates both malignant progression and immune resistance in lung cancer. Clinically, these findings position stemness as a potential biomarker for predicting immunotherapy responsiveness in OSA-associated lung cancer. Patients with high-stemness tumors may be less likely to benefit from immune checkpoint blockade alone and could require combinational strategies targeting stemness pathways to overcome adaptive immune resistance.

Association of stemness scores with clinical features. (A) Stemness was higher in tumors vs. normal tissues. (B) Male patients showed higher stemness than females. (C) No significant difference by age. (D) Metastatic (M1) cases exhibited higher stemness than M0. (E) No clear trend across lymph node stages. (F) High stemness correlated with worse overall survival. (G) Stemness increased with advanced clinical stage. (H) Stemness was elevated in higher T stages.

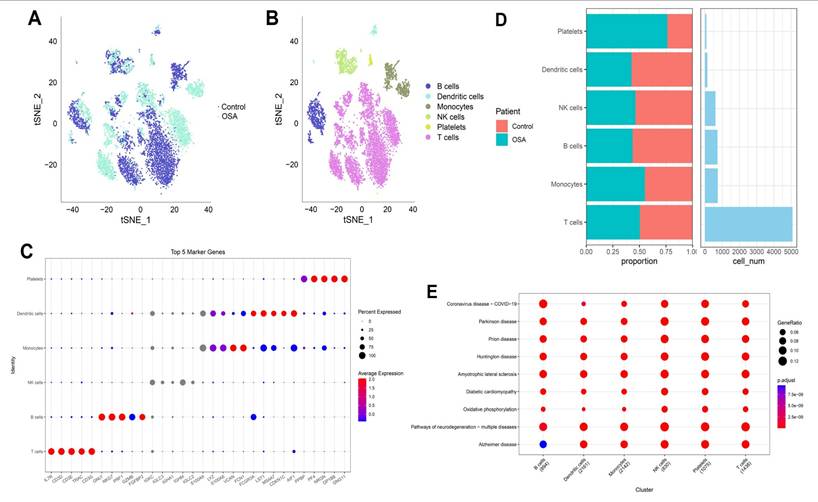

3.8 Single-cell transcriptomic landscape reveals immune cell heterogeneity in OSA-associated lung tissue

Single-cell transcriptomic profiling revealed profound reshaping of the lung immune microenvironment in response to OSA-associated intermittent hypoxia. Dimensionality reduction analyses demonstrated clear segregation of OSA and control cells, reflecting condition-specific transcriptional programs rather than technical artifacts. Within this landscape, we identified six predominant immune populations, including T cells, B cells, NK cells, monocytes, dendritic cells, and platelets, each defined by canonical lineage-specific markers such as CD3D for T cells, MS4A1 for B cells, NKG7 for NK cells, and FCGR3A for monocytes. Notably, T cells and monocytes comprised the largest fractions in OSA lungs, consistent with their central role in hypoxia-driven inflammation. Quantitative comparisons revealed a disproportionate expansion of effector T cells and pro-inflammatory monocytes, with a concomitant reduction in dendritic cells and B cells. This shift suggests a skewing toward cytotoxic and innate effector programs, potentially at the expense of antigen-presenting and humoral immune functions. Such remodeling aligns with previous observations in OSA patients, where intermittent hypoxia enhances systemic inflammation, disrupts adaptive immunity, and promotes an immunosuppressive milieu favorable for tumor initiation. The observed expansion of platelets under hypoxia further underscores the interplay between coagulation, chronic inflammation, and tumor microenvironmental priming. Pathway enrichment analyses provided mechanistic insights into these cellular shifts. Across immune subsets, we detected enrichment in oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neurodegenerative disease-related pathways, reflecting the systemic metabolic burden imposed by intermittent hypoxia. Importantly, the upregulation of mitochondrial stress signatures in T cells and monocytes may amplify reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, fueling DNA damage and oncogenic signaling cascades. Simultaneous enrichment in viral infection and inflammatory signaling pathways highlights an activated, stress-responsive state that could facilitate both tissue injury and immune evasion. Taken together, these findings suggest that OSA-driven intermittent hypoxia orchestrates a dual-edged immune reprogramming process: on one hand, amplifying effector activity and metabolic stress in monocytes and T cells; on the other, diminishing antigen presentation and B-cell-mediated surveillance. Such an imbalance may establish a chronic inflammatory and metabolically perturbed lung environment conducive to fibrosis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and ultimately, malignant transformation. This immune remodeling provides a plausible mechanistic link between OSA and increased lung cancer susceptibility, and establishes a foundation for exploring immunometabolic vulnerabilities in OSA-related oncogenesis (Figure 9). Importantly, the single-cell RNA-seq dataset was derived from non-malignant murine lung tissue exposed to intermittent hypoxia. Therefore, epithelial-like populations identified in this analysis are interpreted as hypoxia-responsive epithelial states rather than premalignant or early neoplastic entities. The observed transcriptional changes reflect hypoxia-induced cellular plasticity, not direct evidence of tumor initiation.

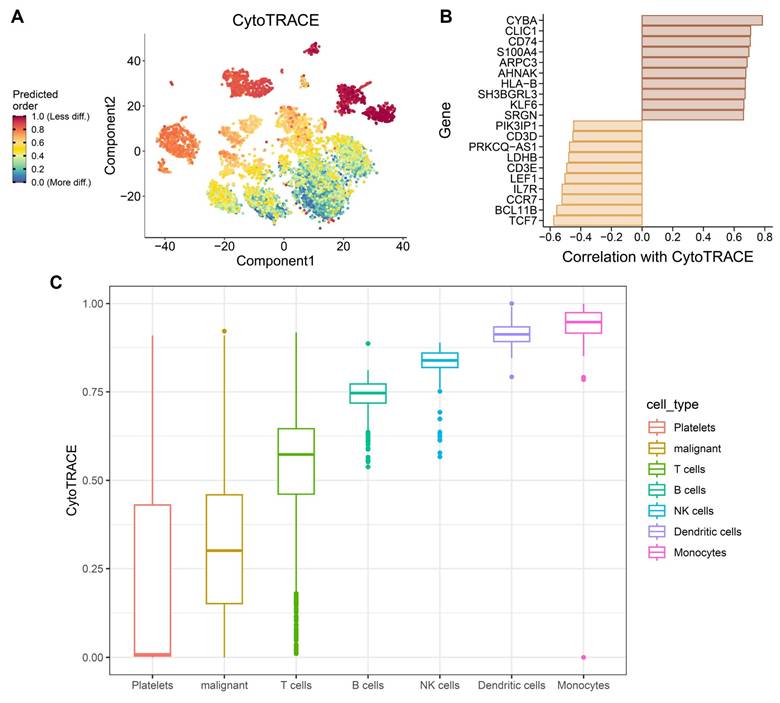

3.9 CytoTRACE analysis highlights stemness heterogeneity and differentiation plasticity under OSA-associated hypoxia

To further characterize how obstructive sleep apnea-related intermittent hypoxia shapes cellular differentiation dynamics in the lung, we applied CytoTRACE to infer stemness across immune and epithelial cell populations in the single-cell dataset. As these analyses were performed using non-malignant murine lung tissue, CytoTRACE scores are interpreted as reflecting hypoxia-induced differentiation plasticity rather than intrinsic tumor stemness or malignant transformation. The analysis revealed striking heterogeneity in differentiation potential (Figure 10A), with subsets of monocytes, dendritic cells, and NK cells displaying high CytoTRACE scores, indicative of preserved stemness and plasticity, whereas platelets and epithelial-like cell populations exhibited lower scores, suggestive of terminal or stress-associated differentiation states. Such divergent differentiation landscapes underscore the impact of hypoxic stress on remodeling the immune and epithelial compartments of the lung. Gene-level correlations further illuminated transcriptional programs associated with stemness. Positive correlations included canonical T cell development and survival factors (TCF7, BCL11B, IL7R, CCR7), as well as regulators of progenitor-like states such as LEF1 and CD3E (Figure 10B). Conversely, negative correlations with metabolic genes (LDHB) and hypoxia-responsive factors (PRKCQ-AS1, SRGN) indicate that mitochondrial dysfunction and stress responses antagonize differentiation potential, reinforcing the theme of mito-nuclear imbalance. This dual signature suggests that intermittent hypoxia simultaneously maintains progenitor-like traits in certain immune subsets while driving metabolic exhaustion in others. At the population level, CytoTRACE stratification demonstrated that monocytes and dendritic cells harbored the highest stemness potential (Figure 10C), consistent with their roles as plastic innate effectors capable of fueling inflammatory remodeling and antigen presentation under stress. NK cells also retained stemness signatures, which may support cytotoxic adaptability but could also contribute to immune dysregulation in a hypoxic microenvironment. In contrast, epithelial-like cell populations displayed low CytoTRACE scores, indicating impaired differentiation and a shift toward metabolic rigidity. This phenotype may reflect the combined impact of intermittent hypoxia on mitochondrial dysfunction and chromatin remodeling, fostering conditions conducive to malignant persistence and resistance to apoptosis. Collectively, these findings highlight a paradoxical role of OSA-driven hypoxia in lung tissues: while it preserves stemness and plasticity in immune populations that may perpetuate chronic inflammation, it simultaneously enforces differentiation arrest and metabolic maladaptation in malignant cells. Such reciprocal programming may create a tumor-promoting ecosystem, where immune cell plasticity supports a pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic niche, while malignant cells capitalize on hypoxia-induced metabolic rewiring to evade immune surveillance. This stemness imbalance provides a mechanistic bridge between OSA pathophysiology and lung cancer progression, suggesting that targeting hypoxia-related stemness pathways could represent a therapeutic avenue. These stemness-associated features reflect altered differentiation states induced by hypoxic stress and should not be interpreted as evidence of malignant transformation.

Association of stemness scores with immune checkpoint expression. (A) Correlation heatmap showing positive associations between stemness score and multiple immune checkpoint genes. (B) Boxplots comparing checkpoint gene expression across high, medium, and low stemness groups.

Association of stemness with TIDE scores. (A) Boxplots showing significantly higher TIDE scores in high-stemness tumors compared with medium- and low-stemness groups. (B) Positive correlation between stemness scores and TIDE values (R = 0.41, p < 2.2e-16).

Immune landscape of OSA and control lungs. (A) t-SNE plots showing global cell distribution (OSA vs. control). (B) Annotation of six immune lineages. (C) Bubble plot of top marker genes per lineage. (D) Proportional changes in immune subsets. (E) Pathway enrichment across clusters.

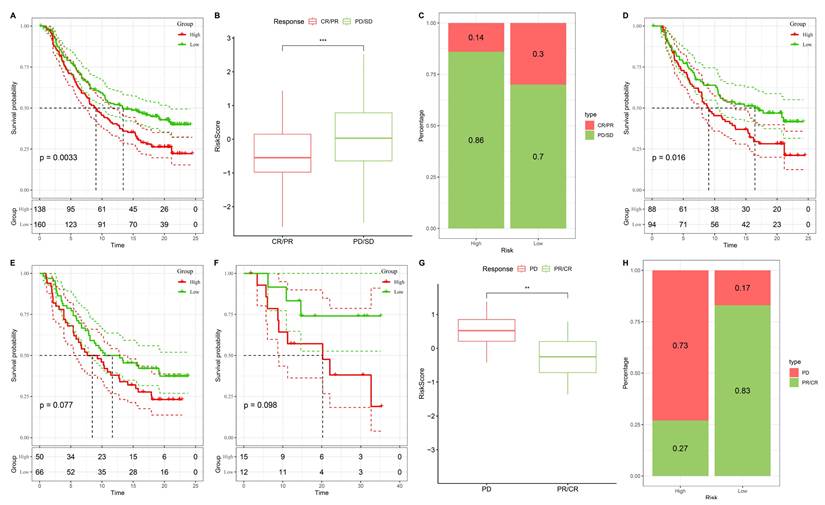

3.10 Stemness-based risk groups predict differential responses to immunotherapy

To further evaluate the predictive value of the stemness-based risk model in the context of immunotherapy, we applied the model to two independent ICB-treated cohorts, IMvigor210 and GSE78820. In the IMvigor210 cohort, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that patients in the high-risk group had significantly shorter overall survival compared with those in the low-risk group (Figure 11A). When stratified by treatment response, non-responders (progressive disease [PD] or stable disease [SD]) exhibited substantially higher risk scores than responders (complete response [CR] or partial response [PR]) (Figure 11B). Consistent with these findings, response distribution analysis showed that clinical benefit (CR/PR) was enriched in the low-risk group, whereas the high-risk group was dominated by PD/SD cases (Figure 11C). Similar trends were observed in the GSE78820 immunotherapy cohort. Kaplan-Meier survival curves consistently demonstrated inferior outcomes in high-risk patients compared with their low-risk counterparts (Figure 11D-F). Boxplot comparisons further indicated that non-responders carried higher risk scores than responders, supporting the robustness of the model across different patient populations (Figure 11G). Finally, response distribution analysis confirmed that the low-risk group was enriched for CR/PR cases, whereas the high-risk group was predominantly composed of non-responders (Figure 11H). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the stemness-based risk score not only stratifies prognosis but also serves as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy efficacy. Patients in the low-risk group are more likely to achieve durable clinical benefit from immune checkpoint blockade, while high-risk patients, characterized by stemness-associated immune evasion, exhibit limited responsiveness. These findings suggest that integrating stemness stratification into clinical decision-making may help identify patients most likely to benefit from immunotherapy and guide the development of rational combination strategies for high-risk individuals.

CytoTRACE-based evaluation of differentiation plasticity in immune and epithelial populations under OSA-associated intermittent hypoxia. (A) CytoTRACE visualization of single-cell transcriptomes, with colors representing predicted differentiation potential (red = less differentiated, blue = more differentiated). (B) Correlation of CytoTRACE scores with gene expression, showing positive associations with stemness-related regulator such as, TCF7, BCL11B, IL7R, and CCR7 and negative correlations with metabolic or stress-response genes including LDHB, and PRKCQ-AS1. (C) Boxplots of CytoTRACE scores across cell types, indicating higher stemness like signatures in monocytes, dendritic cells, and NK cells, while platelets and epithelial-like cell populations exhibited reduced differentiation potential. All cell populations shown are derived from non-malignant lung tissue and reflect hypoxia-induced differentiation plasticity rather than malignant transformation.

Validation of the stemness-based risk model in immunotherapy datasets (IMvigor210 and GSE78820). (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of IMvigor210 showing significantly shorter survival in the high-risk group compared with the low-risk group. (B) Boxplot analysis of IMvigor210 demonstrating that patients with progressive disease (PD) or stable disease (SD) had higher risk scores than those with complete response (CR) or partial response (PR). (C) Distribution of treatment responses in IMvigor210, with the low-risk group enriched for CR/PR and the high-risk group enriched for PD/SD. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of GSE78820 showing inferior survival outcomes in high-risk patients. (E) Subgroup Kaplan-Meier validation in GSE78820 confirming a trend toward reduced survival in the high-risk group. (F) Additional survival validation in a smaller subset of GSE78820, again demonstrating poorer outcomes in high-risk patients. (G) Boxplot analysis of GSE78820 showing higher risk scores in non-responders (PD) compared with responders (CR/PR). (H) Distribution of treatment responses in GSE78820 indicating that the majority of low-risk patients derived clinical benefit (CR/PR), whereas high-risk patients were predominantly non-responders.

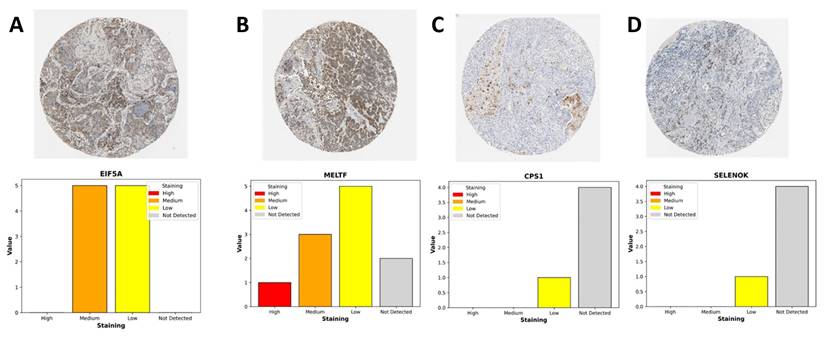

3.11 Immunohistochemical validation of stemness-associated genes in LUAD

To complement our transcriptomic analyses, we next assessed the protein-level expression of representative genes from the stemness-associated signature using immunohistochemistry (IHC) data from the Human Protein Atlas (Figure 12). Consistent with the transcriptional profiles, EIF5A and MELTF displayed prominent staining in LUAD tissues, whereas CPS1 and SELENOK exhibited weak or undetectable expression in most samples. EIF5A showed moderate-to-strong cytoplasmic and nuclear staining in malignant epithelial cells, reflecting its role as a translation initiation factor that supports proliferative and metabolic programs in stemness-high tumors. MELTF, a transferrin receptor homolog involved in iron metabolism and cellular redox balance, demonstrated enriched membranous and cytoplasmic staining, further supporting its function in metabolic reprogramming under hypoxic and stemness-driven conditions. By contrast, CPS1, a key enzyme in the urea cycle, and SELENOK, a regulator of ER-associated protein degradation and redox homeostasis, were largely absent or only weakly expressed in tumor sections. The downregulation of these metabolic regulators is consistent with our transcriptomic findings that stemness-high tumors suppress mitochondrial and antioxidant pathways to favor proliferative adaptability. Quantitative summaries of IHC scoring revealed that the majority of LUAD samples exhibited medium-to-high staining for EIF5A and MELTF, while CPS1 and SELENOK were predominantly categorized as low or not detected. This expression pattern highlights a functional dichotomy: stemness-promoting genes (EIF5A, MELTF) are selectively upregulated at the protein level, whereas metabolic homeostasis genes (CPS1, SELENOK) are suppressed, reinforcing the hypothesis that OSA-associated hypoxia drives a shift toward translational and iron-regulated growth programs while diminishing metabolic resilience. Together, these IHC findings provide orthogonal validation of our multi-omics model, confirming that stemness-associated risk genes are differentially regulated at the protein level in LUAD tissues. This reinforces the biological plausibility of our stemness-based prognostic signature and further illustrates how intermittent hypoxia-driven reprogramming converges on both translational and metabolic axes to support tumor progression.

Immunohistochemical expression of LUAD-associated genes from the Human Protein Atlas. (A) EIF5A: Moderate-to-strong cytoplasmic and nuclear staining observed in malignant epithelial cells, consistent with its role in sustaining translational activity and proliferation.(B) MELTF: Predominantly membranous and cytoplasmic staining enriched in tumor cells, highlighting its involvement in iron metabolism and hypoxia-driven redox regulation.(C) CPS1: Weak or absent cytoplasmic staining, reflecting suppression of urea cycle activity and mitochondrial metabolism in LUAD.(D) SELENOK: Minimal staining in most tumor samples, suggesting downregulation of antioxidant and ER-associated homeostasis functions. Bar plots summarize staining intensity categories (high, medium, low, not detected) across LUAD patient samples.

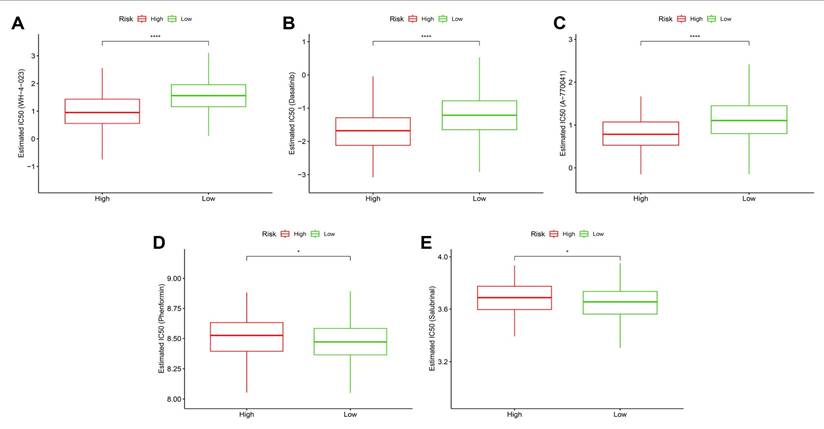

Predicted drug responses in high- vs. low-risk groups. (A-C) High-risk tumors showed significantly lower estimated IC50 values for WH-4023, dasatinib, and A-770041, suggesting higher sensitivity. (D-E) High-risk tumors displayed decreased sensitivity to phenformin and salubrinal.

3.12 Stemness-based risk groups exhibit differential drug sensitivity profiles

To investigate whether the stemness-derived risk signature could inform therapeutic decision-making, we evaluated drug sensitivity patterns between high- and low-risk groups using estimated IC50 values. High-risk tumors consistently demonstrated significantly lower IC50 values for WH-4023, dasatinib, and A-770041 (Figure 13A-C), indicating enhanced susceptibility to these targeted agents. These drugs primarily act on tyrosine kinase and T-cell signaling pathways, suggesting that stemness-driven tumors may be particularly vulnerable to interventions disrupting oncogenic signaling and immune regulation. Similarly, metabolic and stress-response modulators, including phenformin (a mitochondrial complex I inhibitor) and salubrinal (an ER stress modulator), also showed stronger predicted efficacy in the high-risk group (Figure 13D-E). This aligns with prior observations that stemness-high tumors harbor mitochondrial dysfunction and heightened stress responses, rendering them more sensitive to compounds targeting bioenergetic and proteostasis vulnerabilities. Taken together, these findings highlight that OSA-associated stemness not only drives tumor aggressiveness and immune evasion but also defines a distinct therapeutic vulnerability landscape. Patients stratified into the high-risk group may benefit from tailored regimens incorporating kinase inhibitors and metabolic modulators, whereas low-risk patients may require alternative therapeutic strategies. This integration of stemness biology with drug response prediction underscores the translational value of the model in guiding personalized therapy.

4. Discussion

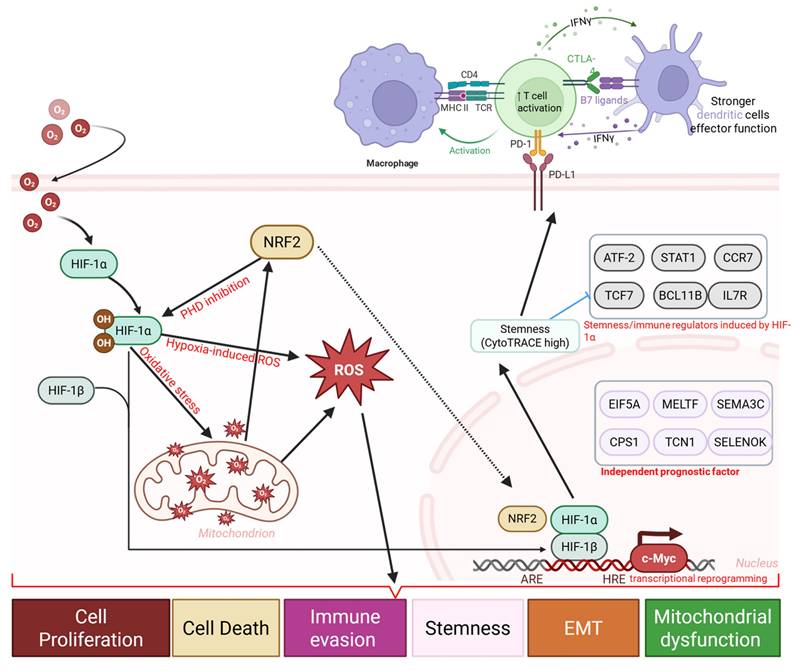

This study provides novel insights into the biological link between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), intermittent hypoxia (IH), and lung cancer progression. By integrating single-cell RNA sequencing, bulk transcriptomics, and computational modeling, we demonstrate that IH is associated with stemness like transcriptional plasticity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and immune remodeling, ultimately contributing to a tumor-promoting microenvironment. These findings complement prior epidemiological evidence linking OSA severity with lung cancer risk and poor outcomes, while offering molecular and cellular context for this association. At the cellular level, our scRNA-seq analysis revealed that IH is accompanied by marked reshaping of the lung immune landscape. Expansion of effector T cells and pro-inflammatory monocytes reflects an activated immune state, whereas concomitant enrichment of regulatory T cells and M2 macrophages suggests a parallel immunosuppressive shift [62, 63]. This duality reflects a well-recognized paradox in cancer biology, wherein chronic inflammation activation promotes tissue remodeling and genomic stress, while immunosuppressive cell populations dampen effective antitumor immunity [64]. Importantly, our CytoTRACE analysis highlighted that IH is associated with stemness-like differentiation plasticity in immune cell populations, sustaining progenitor-like features in monocytes and dendritic cells while epithelial-like cells exhibited stress-associated differentiated states [65]. These findings are consistent with hypoxia-driven activation of HIF-1α and c-Myc pathways, which are known to regulate both stemness and immunometabolism [66]. Notably, as the single-cell analyses were conducted in non-malignant lung tissue, the stemness-associated features observed here are best interpreted as hypoxia-induced cellular plasticity rather than direct evidence of neoplastic transformation. From a metabolic perspective, stemness-high tumors exhibited a striking mito-nuclear imbalance, characterized by downregulation of mitochondrial transcripts and compensatory upregulation of nuclear-encoded oxidative phosphorylation genes [67]. This imbalance may amplify reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, DNA damage, and activation of stress-responsive transcriptional programs, thereby potentially facilitating tumor progression and therapeutic resistance [68]. These results expand upon prior reports linking intermittent hypoxia to mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction, suggesting that metabolic rewiring is a central axis by which OSA promotes oncogenesis [69].

Clinically, the stemness-derived prognostic model demonstrated robust and independent predictive power across TCGA-LUAD and GSE31210 cohorts. Elevated stemness scores were associated with advanced tumor stage, metastatic dissemination, and inferior overall survival, consistent with the established role of stemness in tumor aggressiveness and therapy resistance. Beyond prognostication, our analyses revealed that stemness stratification informs therapeutic responsiveness. High-stemness tumors consistently exhibited immune checkpoint upregulation, elevated TIDE scores, and reduced responsiveness to checkpoint blockade, reflecting a stemness-driven immune-evasive phenotype [70]. These findings resonate with emerging clinical data showing that stemness signatures predict poor response to immunotherapy across multiple cancer types, including NSCLC and melanoma [24, 71]. Our findings support a coherent data-informed mechanistic model in which OSA-associated intermittent hypoxia functions as an upstream microenvironmental stressor that initiates immune and epithelial plasticity. Hypoxia-induced metabolic stress and mitochondrial dysfunction promote inflammatory activation while simultaneously favoring the expansion of immunosuppressive cell populations and immune checkpoint expression. This altered immune landscape creates permissive conditions for stemness-associated tumor programs, which in human LUAD cohorts manifest as immune evasion, reduced immunotherapy responsiveness, and adverse clinical outcomes. From a therapeutic standpoint, our drug sensitivity analysis suggests potential vulnerabilities within stemness-high tumors. Despite immune evasion, high-stemness tumors exhibited heightened sensitivity to kinase inhibitors (dasatinib, A-770041) and metabolic stress modulators (phenformin, salubrinal) [72, 73]. This pattern is consistent with the concept of collateral vulnerabilities, whereby stemness-associated programs impose exploitable metabolic and signaling dependencies [74]. Combination strategies targeting both stemness-associated pathways and immune checkpoints may therefore offer synergistic benefits. For example, dasatinib has been shown to modulate T-cell signaling and suppress hypoxia-induced oncogenic pathways, while Phenformin selectively targets tumors with mitochondrial dysfunction. Such approaches could be particularly valuable in OSA patients, who may harbor biologically distinct tumors with high stemness and poor immunotherapy response [75].

Our findings also carry broader implications for the field of sleep medicine and oncology. The demonstration that IH imprints a durable stemness and immune-escape phenotype in the lung suggests that OSA should be considered not only a comorbidity but also a cancer risk modifier [12]. This raises the possibility that early diagnosis and treatment of OSA, for example with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), may attenuate tumor-promoting pathways. Indeed, clinical studies have shown that CPAP therapy reduces systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, though its impact on cancer incidence remains to be established. Future prospective studies integrating sleep phenotyping with molecular tumor profiling will be critical to validate whether OSA treatment modifies cancer risk and therapeutic response [76, 77].

Hypoxia-driven immune and stemness remodeling in OSA-associated lung cancer. Schematic diagram illustrating a proposed mechanistic framework linking obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)-associated intermittent hypoxia to immune dysfunction and tumor progression. Intermittent hypoxia stabilizes HIF-1α and induces oxidative stress, and metabolic stress, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, and transcriptional reprogramming. These changes promote immune and epithelial plasticity, enrichment of stemness-associated programs, and upregulation of immune checkpoints (PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, B7 ligands), accompanied by T cell activation followed by exhaustion, altered dendritic cell function, and macrophage polarization.

Several limitations warrant consideration. This study primarily relies on computational analyses and publicly available transcriptomic datasets, and although findings were validated across independent human cohorts, experimental validation will be necessary to establish direct causal mechanisms. In addition, the use of murine intermittent hypoxia models and the absence of clinical OSA annotation in LUAD datasets may limit direct translational inference, underscoring the need for prospective, mechanistic studies.

In summary, this study identifies stemness as a key biological and clinical bridge linking OSA-associated intermittent hypoxia to lung cancer progression, Immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance. By integrating single-cell analysis, prognostic modeling, immune landscape profiling, and drug sensitivity prediction, we provide a comprehensive framework that advances understanding of OSA as an oncogenic risk factor. More importantly, our findings highlight actionable vulnerabilities and suggest that integrating stemness-targeted interventions with immunotherapy may improve outcomes in OSA-associated lung cancer, paving the way for precision oncology strategies tailored to patients with sleep-disordered breathing.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, (Figure 14) this integrative single-cell and transcriptomic study provides evidence that obstructive sleep apnea-associated intermittent hypoxia is linked to lung cancer progression through stemness -associated transcriptional plasticity, metabolic dysregulation, and immune remodeling. We demonstrate that stemness-high tumors are characterized by mitochondrial stress-related transcriptional programs, enrichment of developmental signaling pathway, immune checkpoint upregulation, and adverse clinical outcomes, while also exhibiting predicted vulnerabilities to selected kinase inhibitors and metabolic modulators. The stemness-based prognostic model developed in this study was validated across independent cohorts and identified as an independent indicator of patient survival and predicted immunotherapy responsiveness. These findings support stemness as a mechanistic and clinically relevant axis connecting OSA-associated hypoxic stress with tumor aggressiveness, highlight its potential utility as a prognostic biomarker and stratification factor. Future prospective studies integrating clinical OSA phenotyping, patient-derived tumor models, and functional validation will be essential to confirm these observations and refine precision oncology strategies for patients with OSA-related lung cancer.

Abbreviations

OSA: Obstructive sleep apnea

IH: Intermittent hypoxia

NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer

LUAD: Lung adenocarcinoma

scRNA-seq: Single-cell RNA sequencing

UMAP: Uniform manifold approximation and projection

t-SNE: t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

CytoTRACE: Cellular Trajectory Reconstruction Analysis using gene Counts and Expression

TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas

GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus

DEG: Differentially expressed gene

GO: Gene Ontology

KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

ROC: Receiver operating characteristic

AUC: Area under the curve

Cox: Proportional hazards regression

LASSO: Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

CIBERSORT: Cell type Identification by Estimating Relative Subsets of RNA Transcripts

ESTIMATE: Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in MAlignant Tumor tissues using Expression data

TIDE: Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion

IC50: Half maximal inhibitory concentration

PD-1 (PDCD1): Programmed cell death protein 1

PD-L1 (CD274): Programmed death-ligand 1

CTLA4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

LAG3: Lymphocyte-activation gene 3

TIGIT: T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains

CR/PR: Complete response / Partial response

SD/PD: Stable disease / Progressive disease

TME: Tumor microenvironment

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Yi-Ting Wu, Chien-Cheng Chao, Yun-Yu Lin, and Yueh-Yuan Shieh for their excellent technical support at the Laboratory of Research and Medical Education and Research Center, Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) of Taiwan, grant nos. 114-2320-B-393-003, 114-2320-B-393-004, 113-2320-B-393-001, 114-2314-B-038-133-MY3 and 114-2811-B-038-046, and by Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital grant nos. KAFGH_D_114023 and KAFGH_D_114053. The APC was funded by Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital. This work was also financially supported by the Higher Education Sprout Project of the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan and the Health Taiwan Deep Cultivation Project (grant no. A20016).

Availability of data and materials

All datasets and materials generated in this study can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

To improve clarity, readability, and language quality, we used AI-assisted tools during manuscript preparation. All AI-generated suggestions were carefully reviewed, revised, and verified by the authors. The authors assume complete accountability for the final manuscript's content, accuracy, and integrity.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. JAMA. 2020;323:1389-400

2. Tasali E, Pamidi S, Covassin N, Somers VK. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiometabolic Disease: Obesity, Hypertension, and Diabetes. Circ Res. 2025;137:764-87

3. Gawrys B, Silva TW, Herness J. Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults: Common Questions and Answers. Am Fam Physician. 2024;110:27-36

4. Redline S, Azarbarzin A, Peker Y. Obstructive sleep apnoea heterogeneity and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:560-73

5. Javaheri S, Javaheri S, Somers VK, Gozal D, Mokhlesi B, Mehra R. et al. Interactions of Obstructive Sleep Apnea with the Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Disease, Part 1: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:1208-23

6. Yeghiazarians Y, Jneid H, Tietjens JR, Redline S, Brown DL, El-Sherif N. et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144:e56-e67

7. Cheong AJY, Tan BKJ, Teo YH, Tan NKW, Yap DWT, Sia CH. et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19:469-75

8. Yao J, Duan R, Li Q, Mo R, Zheng P, Feng T. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and risk of lung cancer: findings from a collection of cohort studies and Mendelian randomization analysis. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1346809

9. Justeau G, Gervès-Pinquié C, Le Vaillant M, Trzepizur W, Meslier N, Goupil F. et al. Association Between Nocturnal Hypoxemia and Cancer Incidence in Patients Investigated for OSA: Data from a Large Multicenter French Cohort. Chest. 2020;158:2610-20

10. Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, Cubillos C, Veatch OJ, Garcia-Rio F, Gozal D, Martinez-Garcia MA. Potential Pathophysiological Pathways in the Complex Relationships between OSA and Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023 15

11. Tan BKJ, Teo YH, Tan NKW, Yap DWT, Sundar R, Lee CH. et al. Association of obstructive sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoxemia with all-cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18:1427-40

12. Marrone O, Bonsignore MR. Obstructive sleep apnea and cancer: a complex relationship. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26:657-67

13. Wang M, Herbst RS, Boshoff C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2021;27:1345-56

14. Pabst L, Lopes S, Bertrand B, Creusot Q, Kotovskaya M, Pencreach E. et al. Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in the Era of Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 24

15. Hapke RY, Haake SM. Hypoxia-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020;487:10-20

16. Liao C, Liu X, Zhang C, Zhang Q. Tumor hypoxia: From basic knowledge to therapeutic implications. Semin Cancer Biol. 2023;88:172-86

17. Cui Z, Ruan Z, Li M, Ren R, Ma Y, Zeng J. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea promotes the progression of lung cancer by modulating cancer cell invasion and cancer-associated fibroblast activation via TGFβ signaling. Redox Rep. 2023;28:2279813

18. Bhagavan H, Wei AD, Oliveira LM, Aldinger KA, Ramirez JM. Chronic intermittent hypoxia elicits distinct transcriptomic responses among neurons and oligodendrocytes within the brainstem of mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2024;326:L698-l712

19. Khalyfa A, Warren W, Andrade J, Bottoms CA, Rice ES, Cortese R. et al. Transcriptomic Changes of Murine Visceral Fat Exposed to Intermittent Hypoxia at Single Cell Resolution. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 22

20. Alexander MJ, Budinger GRS, Reyfman PA. Breathing fresh air into respiratory research with single-cell RNA sequencing. Eur Respir Rev. 2020 29

21. Cortese R, Adams TS, Cataldo KH, Hummel J, Kaminski N, Kheirandish-Gozal L. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq uncovers cellular heterogeneity and provides a signature for paediatric sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2023 61

22. Wu G, Lee YY, Gulla EM, Potter A, Kitzmiller J, Ruben MD. et al. Short-term exposure to intermittent hypoxia leads to changes in gene expression seen in chronic pulmonary disease. Elife. 2021 10

23. Liu L, Zhang M, Cui N, Liu W, Di G, Wang Y. et al. Integration of single-cell RNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq to construct liver hepatocellular carcinoma stem cell signatures to explore their impact on patient prognosis and treatment. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0298004

24. Zhang Z, Wang ZX, Chen YX, Wu HX, Yin L, Zhao Q. et al. Integrated analysis of single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing data reveals a pan-cancer stemness signature predicting immunotherapy response. Genome Med. 2022;14:45

25. Wang X, Chen X, Zhao M, Li G, Cai D, Yan F. et al. Integration of scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq constructs a stemness-related signature for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy responses in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:13823-39

26. Qi P, Qi B, Ding Y, Sun J, Gu C, Huo S. et al. Implications of obstructive sleep apnea in lung adenocarcinoma: A valuable omission in cancer prognosis and immunotherapy. Sleep Med. 2023;107:268-80

27. Hu M, Li Y, Lu Y, Wang M, Li Y, Wang C. et al. The regulation of immune checkpoints by the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. PeerJ. 2021;9:e11306

28. Su BH, Kumar S, Cheng LH, Chang WJ, Solomon DD, Ko CC. et al. Multi-omics profiling reveals PLEKHA6 as a modulator of β-catenin signaling and therapeutic vulnerability in lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2025;15:3106-27

29. Solomon DD, Ko CC, Chen HY, Kumar S, Wulandari FS, Xuan DTM. et al. A machine learning framework using urinary biomarkers for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma prediction with post hoc validation via single-cell transcriptomics. Brief Bioinform. 2025 26

30. Chiang YC, Wang CY, Kumar S, Hsieh CB, Chang KF, Ko CC. et al. Metal ion transporter SLC39A14-mediated ferroptosis and glycosylation modulate the tumor immune microenvironment: pan-cancer multi-omics exploration of therapeutic potential. Cancer Cell Int. 2025;25:363

31. Hu C, Li T, Xu Y, Zhang X, Li F, Bai J. et al. CellMarker 2.0: an updated database of manually curated cell markers in human/mouse and web tools based on scRNA-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D870-d6

32. Kumar S, Wu CC, Wulandari FS, Chiao CC, Ko CC, Lin HY. et al. Integration of multi-omics and single-cell transcriptome reveals mitochondrial outer membrane protein-2 (MTX-2) as a prognostic biomarker and characterizes ubiquinone metabolism in lung adenocarcinoma. J Cancer. 2025;16:2401-20

33. Wu YJ, Chiao CC, Chuang PK, Hsieh CB, Ko CY, Ko CC. et al. Comprehensive analysis of bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data reveals Schlafen-5 (SLFN5) as a novel prognosis and immunity. Int J Med Sci. 2024;21:2348-64

34. Li CY, Anuraga G, Chang CP, Weng TY, Hsu HP, Ta HDK. et al. Repurposing nitric oxide donating drugs in cancer therapy through immune modulation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:22

35. Ye PH, Li CY, Cheng HY, Anuraga G, Wang CY, Chen FW. et al. A novel combination therapy of arginine deiminase and an arginase inhibitor targeting arginine metabolism in the tumor and immune microenvironment. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:1952-69

36. Gulati GS, Sikandar SS, Wesche DJ, Manjunath A, Bharadwaj A, Berger MJ. et al. Single-cell transcriptional diversity is a hallmark of developmental potential. Science. 2020;367:405-11

37. Xuan DTM, Yeh IJ, Liu HL, Su CY, Ko CC, Ta HDK. et al. A comparative analysis of Marburg virus-infected bat and human models from public high-throughput sequencing data. Int J Med Sci. 2025;22:1-16

38. Anuraga G, Lang J, Xuan DTM, Ta HDK, Jiang JZ, Sun Z. et al. Integrated bioinformatics approaches to investigate alterations in transcriptomic profiles of monkeypox infected human cell line model. J Infect Public Health. 2024;17:60-9

39. Xuan DTM, Yeh IJ, Wu CC, Su CY, Liu HL, Chiao CC. et al. Comparison of Transcriptomic Signatures between Monkeypox-Infected Monkey and Human Cell Lines. J Immunol Res. 2022;2022:3883822

40. Wu YH, Yeh IJ, Phan NN, Yen MC, Hung JH, Chiao CC. et al. Gene signatures and potential therapeutic targets of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)-infected human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54:845-57

41. Cheng LC, Kao TJ, Phan NN, Chiao CC, Yen MC, Chen CF. et al. Novel signaling pathways regulate SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infectious disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24321

42. Chuang P-K, Chang K-F, Chang C-H, Chen T-Y, Wu Y-J, Lin H-R. et al. Comprehensive Bioinformatics Analysis of Glycosylation-Related Genes and Potential Therapeutic Targets in Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025;26:1648

43. Chen HK, Chen YL, Wang CY, Chung WP, Fang JH, Lai MD. et al. ABCB1 Regulates Immune Genes in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2023;15:801-11

44. Xuan DTM, Wu CC, Wang WJ, Hsu HP, Ta HDK, Anuraga G. et al. Glutamine synthetase regulates the immune microenvironment and cancer development through the inflammatory pathway. Int J Med Sci. 2023;20:35-49

45. Xuan DTM, Yeh IJ, Su CY, Liu HL, Ta HDK, Anuraga G. et al. Prognostic and Immune Infiltration Value of Proteasome Assembly Chaperone (PSMG) Family Genes in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Int J Med Sci. 2023;20:87-101

46. Wang CY, Xuan DTM, Ye PH, Li CY, Anuraga G, Ta HDK. et al. Synergistic suppressive effects on triple-negative breast cancer by the combination of JTC-801 and sodium oxamate. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:4661-77

47. Fu J, Li K, Zhang W, Wan C, Zhang J, Jiang P. et al. Large-scale public data reuse to model immunotherapy response and resistance. Genome Med. 2020;12:21

48. Choy TK, Wang CY, Phan NN, Khoa Ta HD, Anuraga G, Liu YH. et al. Identification of Dipeptidyl Peptidase (DPP) Family Genes in Clinical Breast Cancer Patients via an Integrated Bioinformatics Approach. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 11

49. Khoa Ta HD, Tang WC, Phan NN, Anuraga G, Hou SY, Chiao CC. et al. Analysis of LAGEs Family Gene Signature and Prognostic Relevance in Breast Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 11

50. Yeh IJ, Wang CY, Phan NN, Xuan DTM, Ko CC, Kumar S. et al. Decoding Short- and Long-Term Cellular Adaptations to Cr(VI) Exposure Through High-Throughput Transcriptomics. Int J Med Sci. 2026;23:113-25

51. Wang CY, Chao YJ, Chen YL, Wang TW, Phan NN, Hsu HP. et al. Upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and the lipid metabolism pathway promotes carcinogenesis of ampullary cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:256-69

52. Meng W, Xu X, Xiao Z, Gao L, Yu L. Cancer Drug Sensitivity Prediction Based on Deep Transfer Learning. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 26

53. Chen YL, Wang CY, Fang JH, Hsu HP. Serine/threonine-protein kinase 24 is an inhibitor of gastric cancer metastasis through suppressing CDH1 gene and enhancing stemness. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11:4277-93

54. Kao TJ, Wu CC, Phan NN, Liu YH, Ta HDK, Anuraga G. et al. Prognoses and genomic analyses of proteasome 26S subunit, ATPase (PSMC) family genes in clinical breast cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:17970

55. Anuraga G, Tang WC, Phan NN, Ta HDK, Liu YH, Wu YF. et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Prognostic and Genetic Signatures for General Transcription Factor III (GTF3) in Clinical Colorectal Cancer Patients Using Bioinformatics Approaches. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2021;43:2-20

56. Chen PS, Hsu HP, Phan NN, Yen MC, Chen FW, Liu YW. et al. CCDC167 as a potential therapeutic target and regulator of cell cycle-related networks in breast cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:4157-81

57. Ta HDK, Minh Xuan DT, Tang WC, Anuraga G, Ni YC, Pan SR. et al. Novel Insights into the Prognosis and Immunological Value of the SLC35A (Solute Carrier 35A) Family Genes in Human Breast Cancer. Biomedicines. 2021 9

58. Chiao CC, Liu YH, Phan NN, An Ton NT, Ta HDK, Anuraga G. et al. Prognostic and Genomic Analysis of Proteasome 20S Subunit Alpha (PSMA) Family Members in Breast Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 11

59. Xuan DTM, Wu CC, Kao TJ, Ta HDK, Anuraga G, Andriani V. et al. Prognostic and immune infiltration signatures of proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase (PSMD) family genes in breast cancer patients. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:24882-913

60. Anuraga G, Wang WJ, Phan NN, An Ton NT, Ta HDK, Berenice Prayugo F. et al. Potential Prognostic Biomarkers of NIMA (Never in Mitosis, Gene A)-Related Kinase (NEK) Family Members in Breast Cancer. J Pers Med. 2021 11

61. Ta HDK, Wang WJ, Phan NN, An Ton NT, Anuraga G, Ku SC. et al. Potential Therapeutic and Prognostic Values of LSM Family Genes in Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021 13

62. Sun B, Long Y, Xu G, Chen J, Wu G, Liu B. et al. Acute hypoxia modulate macrophage phenotype accompanied with transcriptome re-programming and metabolic re-modeling. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1534009

63. Courvan EMC, Parker RR. Hypoxia and inflammation induce synergistic transcriptome turnover in macrophages. Cell Rep. 2024;43:114452

64. Li L, Yu R, Cai T, Chen Z, Lan M, Zou T. et al. Effects of immune cells and cytokines on inflammation and immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106939

65. Mortezaee K, Majidpoor J. The impact of hypoxia on immune state in cancer. Life Sci. 2021;286:120057

66. Contreras-Lopez R, Elizondo-Vega R, Paredes MJ, Luque-Campos N, Torres MJ, Tejedor G. et al. HIF1α-dependent metabolic reprogramming governs mesenchymal stem/stromal cell immunoregulatory functions. Faseb j. 2020;34:8250-64

67. Zheng XX, Chen JJ, Sun YB, Chen TQ, Wang J, Yu SC. Mitochondria in cancer stem cells: Achilles heel or hard armor. Trends Cell Biol. 2023;33:708-27

68. Jomova K, Alomar SY, Valko R, Fresser L, Nepovimova E, Kuca K. et al. Interplay of oxidative stress and antioxidant mechanisms in cancer development and progression. Arch Toxicol. 2025

69. Prabhakar NR, Peng YJ, Nanduri J. Hypoxia-inducible factors and obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:5042-51

70. Liu Q, Lei J, Zhang X, Wang X. Classification of lung adenocarcinoma based on stemness scores in bulk and single cell transcriptomes. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:1691-701

71. Zheng J, Lin H, Ye W, Du M, Huang C, Fan J. Single-cell and multi-omics analysis reveals the role of stem cells in prognosis and immunotherapy of lung adenocarcinoma patients. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1634830

72. Liu G, Jin Z, Lu X. Differential Targeting of Gr-MDSCs, T Cells and Prostate Cancer Cells by Dactolisib and Dasatinib. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 21

73. Pemovska T, Bigenzahn JW, Srndic I, Lercher A, Bergthaler A, César-Razquin A. et al. Metabolic drug survey highlights cancer cell dependencies and vulnerabilities. Nat Commun. 2021;12:7190

74. Bayik D, Lathia JD. Cancer stem cell-immune cell crosstalk in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:526-36

75. Harrington P, Dillon R, Radia D, Rousselot P, McLornan DP, Ong M. et al. Differential inhibition of T-cell receptor and STAT5 signaling pathways determines the immunomodulatory effects of dasatinib in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2023;108:1555-66

76. Meliante PG, Zoccali F, Cascone F, Di Stefano V, Greco A, de Vincentiis M. et al. Molecular Pathology, Oxidative Stress, and Biomarkers in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 24

77. Srivali N, De Giacomi F. Does CPAP increase or protect against cancer risk in OSA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2025;29:175

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: han86449com (Chien-Han Yuan), yungkuonsysu.edu.tw (Yuen-Jung Wu).

Corresponding authors: han86449com (Chien-Han Yuan), yungkuonsysu.edu.tw (Yuen-Jung Wu).

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact